Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

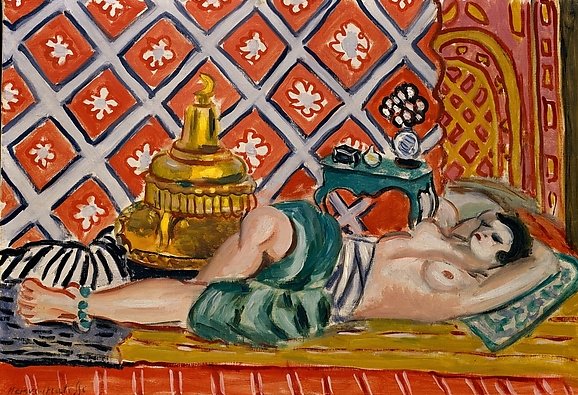

Henri Matisse’s “Reclining Odalisque” (1926) distills the energy of his Nice period into a compact interior where pattern, color, and the languid body negotiate a poised harmony. A woman reclines across a striped floor covering, her head propped on a cushion, her torso opened to the light, while a wall of orange diamonds with white floral emblems presses forward like a radiant tapestry. A turquoise side table with small studio objects, a zebra-striped cushion, and a gleaming gilt vessel complete the stage. The space is shallow and deliberately theatrical, yet the human presence is unforced. Matisse’s aim is not narrative but orchestration: to show how calm can be built from strong contrasts when intervals and edges are tuned with care.

The Nice Period And The Decorative Studio

By the mid-1920s, Matisse had exchanged the shock of Fauvism for a lyrical classicism that favored sustained chords over clashing bursts. Working in bright Riviera rooms, he arranged models among patterned textiles, screens, and portable props that could be recomposed like musical phrases. The odalisque motif—historically a European fantasy—served as a flexible studio device, granting permission for repose, drapery, and abundant ornament without obliging anecdote. “Reclining Odalisque” shows this method at full maturity: an intimate scale, a controlled stage, and a body that anchors rather than dominates the decorative field.

Composition As A Diagonal Lullaby

The composition hinges on a long diagonal from lower left to upper right. The model’s outstretched legs establish the line, which travels through hip and shoulder to the pillow beneath her head. Countering this sweep, the turquoise table rises in a near-vertical accent, and the gold vessel presents a rounded mass that weights the left half. The tiled floor at the bottom edge echoes the diagonal with its striped border, while the wall pattern sets a cross-rhythm of diamonds. These interlocking movements keep the painting from slackening into simple repose; instead, the eye moves in looping circuits—foot to vessel to table to face and back—at an adagio tempo that suits the subject.

Pattern As Structure Rather Than Ornament

Across the back, the orange-and-white wall reads as a complete system of rhythm. Each diamond is framed by a cool blue-gray outline that keeps the warm field from overwhelming the figure. The repeated four-petal emblems inside the diamonds pulse like soft percussion, pacing the background and preventing the space from dissolving. At the lower edge, a striped run of terracotta delivers a slower meter that grounds the reclining body. The zebra cushion at left and the basketlike motif on the right add small counter-themes. Nothing is purely decorative; every pattern clarifies planes and stabilizes the body within the shallow room.

Color As Architectural Chord

The palette centers on a hot–cool dialogue. The wall’s saturated orange saturates the room with warmth; the turquoise of the table and the cool blue-gray outlines introduce a counterweight. The model’s flesh is a chord of apricot, pearl, and muted rose that borrows heat from the wall yet retains its own temperature through cooler half-tones at the ribcage and thigh. The golden vessel concentrates the warm register into a single metallic mass, answering the wall while offering a different surface—reflective, weighty, and rounded. The striped floor and greenish shorts modulate warmth with olive notes, so the figure does not float. White is rarely pure; it’s mixed to pearly tones that admit neighboring color and fold the figure into the air of the room.

The Reclining Figure And Modern Agency

Although the theme carries an Orientalist history, Matisse treats the model as a contemporary collaborator rather than a fantasy type. Her pose is expansive but composed: one arm bent behind the head, the other dropped along the torso; the legs relaxed with a slight bend to keep the diagonal alive. The bracelet at the ankle and the loose shorts offer touches of cool green that echo the table and quiet the wall’s heat. The face, rendered with simplified planes and a compact red of the lips, holds the room gently without theatricality. The figure’s purpose is structural—an interval of warm, living color that locks the patterned surfaces into accord.

The Gilded Vessel As Pictorial Counterweight

At the lower left rises a gleaming, tiered brass form, at once architectural and ornamental. Its scalloped edge, dark arabesque feet, and dome-like lid rhyme with the arcs of the model’s knee and shoulder while concentrating the orange register into a singular object. Chromatically it stabilizes the wall; compositionally it prevents the diagonal body from sliding out of the frame. Matisse places the vessel so its edge nearly meets the table’s leg, creating a hinge that binds the left and center zones and keeps the picture’s energy circulating.

The Turquoise Table And The Studio’s Self-Awareness

The small table—eccentric in color and silhouette—signals the self-awareness of the studio. On it sit a dark box, a small vase with pale blossoms, and a cup. These items are not anecdotes; they are measured accents. The blossoms repeat the wall’s white emblems in a higher register, the box offers a compact block of near-black to stabilize tonal range, and the cup’s highlight keeps the cool chord bright. The table’s thin, striding legs add a playful rhythm that echoes the striping at the bottom edge and articulates the shallow depth without undermining the surface.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Edge

Matisse’s contour carries the authority of the image. The torso’s top edge swings in a supple arc, tightening where bone nears the skin at the shoulder, then relaxing along the flank. The thigh is drawn with a single curve that changes pressure subtly as it rounds the knee. The face remains masklike and legible, made from a few planes and dark strokes that resist fuss. Even the vessel and table are drawn with living edges—slightly irregular ellipses and flaring legs that announce the hand. These lines do not divide so much as enliven; they let color act while keeping forms coherent.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The light is not spotlight but a generous Mediterranean diffusion. Shadows are chromatic—violet in the underarm, olive along the shorts, cool gray along the pillow—and they transition softly, allowing color to carry modeling. Highlights are small and specific: a pale note on the shoulder, a glint on the vessel, a shine on the cup. Because the light is spread rather than concentrated, the painting reads as a sustained chord, not a dramatic instant. This is central to the Nice period’s ethos: intensity built from relation, not from theatrical contrast.

Textiles And The Intelligence Of Touch

Material differences are registered through touch. The cushion’s zebra stripes are dragged with a dry brush so white breaks into the weave, suggesting nap without imitation. The shorts are painted with heavier, rounded strokes that give cloth weight; the pillow’s edge is softened with thin scumbles that let the ground breathe through and feel like compressed cotton. The wall pattern is handled with quick, repeated notes—consistent enough to read as fabric, variable enough to stay human. This variety of touch persuades the eye that the room contains distinct substances while insisting on paint’s primacy.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

The painting holds depth on a short leash. The floor tilts forward, the wall presses close, and the objects crowd the figure, yet overlaps and small cast shadows keep everything believable. The body occupies a shallow trough of space just wide enough to breathe. This productive flatness ensures that the viewer’s attention remains on the surface where color and pattern do their work. The scene is less a window than a tapestry within which objects and body interlock as shapes.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse’s favored musical analogy is palpable here. The wall’s diamonds beat a regular meter; the striped floor adds a slower bass line; the diagonal figure sings a legato melody; the table and vessel chime as bright chords. Looking proceeds in measured phrases. One follows the wall’s diagonals to the table, crosses to the face, slides along the torso, rests at the vessel’s dome, and returns by way of the foot. Each pass reveals new harmonies: a white blossom answering a wall emblem, a turquoise table echoing the cool in the bracelet, a warm tile balancing the red of the lips.

Orientalism Reconsidered And Redirected

The historic odalisque trope is present but rethought. Matisse keeps props—textiles, cushion, ornamental vessel—but removes spectacle. The model’s modern haircut and unaffected posture, the studio table with everyday objects, and the democratic treatment of figure and ground counter the fantasy of a distant harem. Here, the “exotic” has migrated into formal domains—pattern, color, rhythm—where it applies to every element equally. In this redistribution lies the painting’s ethical clarity: the decorative is not a mask for otherness; it is a method for making concord.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Reclining Odalisque” converses with other Nice interiors from 1925–1926. It shares with “Odalisque with Green Scarf” the monumental brass object and the shallow stage, yet here the wall pattern carries a stronger, more geometric beat. Compared with the pearly calm of “The Pink Tablecloth,” this canvas pushes the chord toward heat while maintaining balance through cool counterweights. The flattened interlocking shapes anticipate the late paper cut-outs, where figure and ground become unequivocal color forms. Throughout these dialogues the purpose remains constant: to craft a modern harmony by spacing differences just so.

Material Presence And Evidence Of Process

The surface remembers its making. A shifted outline on the thigh has been softened; a diamond in the wall shows correction where blue was repainted to renew the cadence; a highlight on the vessel has been lowered to match the table’s value. These pentimenti do not disturb the calm—they deepen it. They show that the equilibrium we feel is the product of adjustments, not an automatic formula. The painting is serene because it is earned.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

Despite saturated color and pattern, the psychological register is restful. The model’s eyes are gently closed or lowered; the mouth is small and calm. The studio props keep the scene domestic and present-tense. As the viewer follows the diagonal and re-hears the wall’s beat, the painting subtly regulates attention. It is less a fantasy than a crafted mood, a chamber where looking slows and sensation is held without strain.

Why The Painting Endures

The work endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Each return reveals a new hinge: a cool note in the bracelet recruiting the table’s turquoise; a white petal in the wall aligning with the cup’s highlight; a terracotta stripe balancing the blush in the lips; a soft gray shadow on the pillow that clarifies the arm’s turn. None of these discoveries exhausts the image because the underlying order is generous. The painting houses many small consonances under one broad, steady chord.

Conclusion

“Reclining Odalisque” demonstrates Matisse’s Nice-period conviction that the decorative can be profound. A patterned wall, a striped floor, a glinting vessel, a small table, and a reclining body are arranged so color becomes architecture, pattern becomes grammar, and contour becomes breath. The space is shallow but sufficient; the light is soft yet clarifying. Without narrative fanfare, the painting achieves a lucid calm, proving that intensity and repose are not opposites but partners when relations are set with intelligence and touch. It is a room-sized melody, warm and poised, that continues to sound long after the first glance.