Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

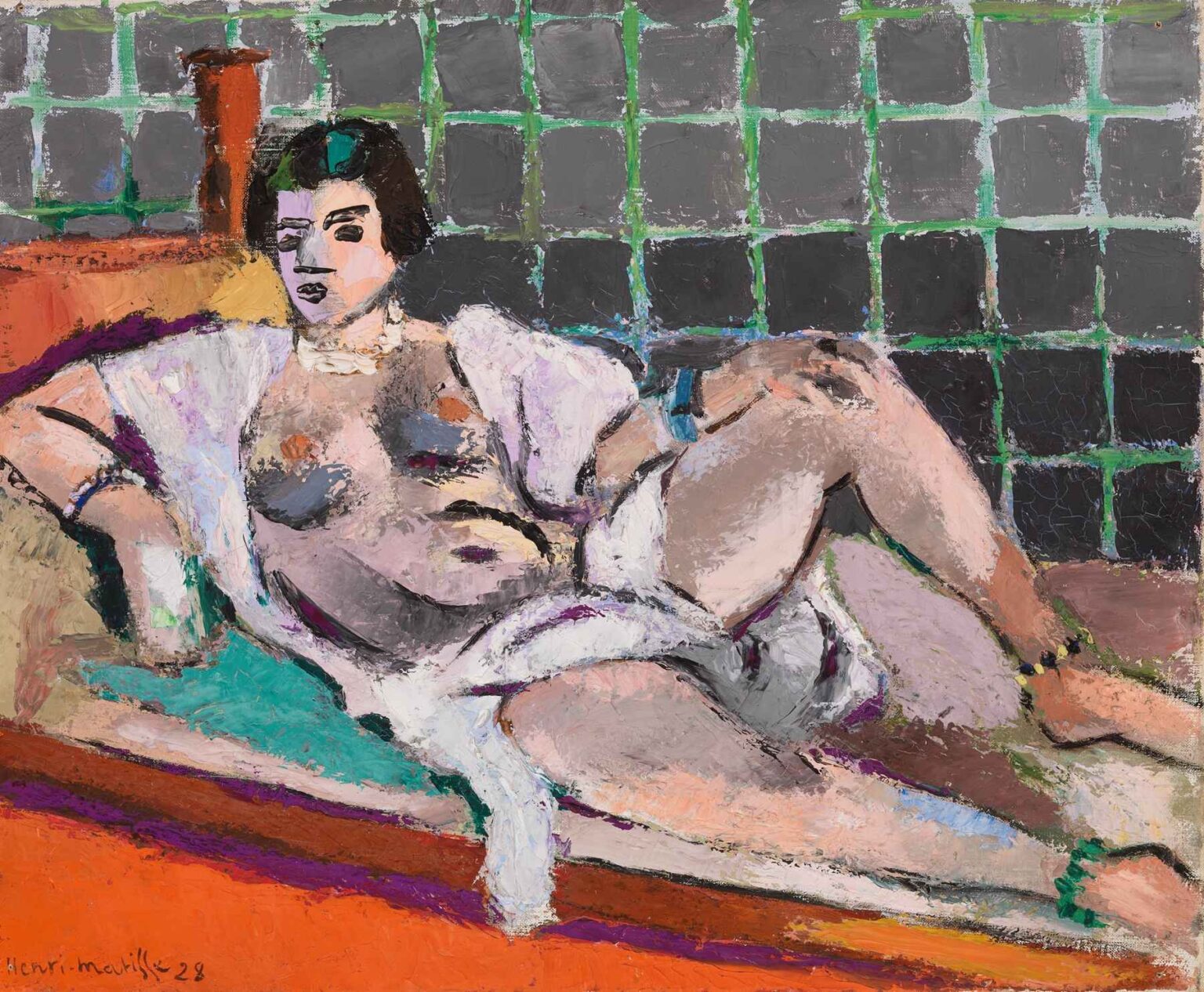

Henri Matisse’s Reclining Odalisque (1928) stands at the crossroads of his Fauvist beginnings and his later decorative abstractions, offering a masterful fusion of color, form, and painterly tactility. At nearly two meters wide, the canvas presents a single female figure in repose, her body rendered in pastel pinks, grays, and whites, set against a boldly patterned environment of architectural grids and vibrant foreground planes. Far from a traditional Orientalist fantasy, Matisse transforms the odalisque motif into a study of painterly surface and chromatic harmony. In the years following World War I, he increasingly pursued flattening of space, rhythmic patterning, and expressive brushwork—elements that converge in Reclining Odalisque to create both a striking visual spectacle and an intimate meditation on the female form. This analysis will explore the painting’s historical context, compositional architecture, use of color and light, spatial treatment, brushwork technique, thematic resonances, emotional impact, position within Matisse’s oeuvre, and lasting influence.

Historical Context

By 1928, Henri Matisse had already established himself as a leading voice of modernism. His early Fauvist period (1905–1908) had shocked the art world with its liberated, non-naturalistic use of color. In the 1910s, he turned toward decorative interiors and still lifes, grounding his chromatic exuberance in patterned surfaces and flattened pictorial spaces. The aftermath of World War I deepened Matisse’s conviction that art could provide emotional renewal and aesthetic solace. From the mid-1920s onward, he embarked on voyages to North Africa—including Algeria and Morocco—immersing himself in Moorish architecture, Islamic tile work, and the region’s unique quality of light. The odalisque theme, long a staple of Orientalist painting, offered Matisse a framework to explore reclining female figures within richly decorative settings. Yet unlike nineteenth-century predecessors, he internalized these influences, infusing them into his signature modernist language. Reclining Odalisque crystallizes this synthesis, reflecting both his exposure to North African motifs and his ongoing quest to harmonize figure and décor.

Subject and Compositional Architecture

The central subject of Reclining Odalisque is a nude woman posed in profile on a low divan. Her left elbow rests on a cushion, supporting her slightly propped head, while her right arm drapes gracefully across her thighs. The legs extend diagonally toward the lower right corner, creating a dynamic oblique axis that energizes the composition. Behind her, the wall is treated as a grid of gray squares segmented by neon-green lines, evoking architecture, tile work, or even the framework of a modernist abstraction. The foreground is anchored by a vibrant orange plane, punctuated by a thin band of violet that separates floor from wall. This deliberate segmentation of pictorial space—foreground, figure, and background—establishes a structural clarity. Yet Matisse undermines rigid geometry with the sensual curves of the odalisque’s body and the painterly liveliness of his brushwork. The result is a balanced yet dynamic arrangement: the diagonal sweep of the figure counterpoints the orthogonal grid, generating both tension and harmony.

Use of Color and Light

Color in Reclining Odalisque operates as the film through which form emerges and emotion is conveyed. Matisse applies a restricted yet powerful palette: the odalisque’s flesh is composed of muted pinks, grays, and creams, all modulated through thick, impasto strokes that reveal underlying layers of yellow or lavender. These warm flesh tones stand out against the cool neutrality of the gray grid, while the neon-green lines of the framework introduce an electric vitality. The vibrant orange foreground provides a warm echo of the body’s highlights, creating chromatic resonance between figure and ground. Light is suggested rather than modeled: instead of chiaroscuro, Matisse relies on sequence of hue—lighter pinks marking planes of the torso, cooler grays delineating shadowed recesses. This approach makes color itself the vehicle of illumination, turning the figure into a locus of hue rather than form. The interplay of warm and cool, neutral and saturated, yields an optical vibration that animates both body and environment.

Spatial Treatment and Flattening

Although Reclining Odalisque depicts a seemingly coherent interior, Matisse deliberately flattens the depth to emphasize surface structure. The bold horizontal band of orange in the foreground reads as a flat color field rather than a floor plane, while the grid behind functions as both wall and abstract pattern. The odalisque floats between these two discrete fields: her body overlaps the orange strip but remains distinct from the grid. Overlapping elements—arm over thigh, thigh over floor—provide shallow spatial cues, yet no vanishing point or deep recession is evident. The grid’s strict orthogonals conflict with the body’s sinuous curves, further collapsing traditional perspectival logic. In this flattening, Matisse aligns figure and décor on the same pictorial plane, inviting viewers to engage with the painting as a unified tapestry of color, line, and brushwork rather than an illusory window into a room.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Matisse’s technique here is boldly painterly. The odalisque’s flesh reveals thick impasto applied with a palette knife or a heavily loaded brush, each stroke retaining its own textural identity. In places, the underlying ground shows through, lending depth to the painted surface. The grid and floor planes, by contrast, receive more even, moderately textured passages, allowing the figure to dominate in gestural richness. The neon-green grid lines are scumbled with quickly lifted strokes, exposing dashes of underlying gray. The orange foreground incorporates rough, directional marks that catch the light differently across its expanse. This juxtaposition of skeletal grids, solid color fields, and tactile flesh strokes creates a dynamic surface interplay. Viewers can trace the motion of Matisse’s hand, feeling the energy of each arc and dab, while also appreciating the overarching compositional coherence.

Symbolism and Thematic Resonances

While Matisse’s odalisques are often read through their Orientalist precedent, Reclining Odalisque transcends exotic fantasy. The African sculpture that appears in earlier odalisque works is absent here, yet the grid’s neon lines and the figure’s languid pose evoke a modernist rethinking of spatial ornamentation more than a depiction of a specific locale. The grid may reference Moorish tile or contemporary architecture, hinting at the intersection of tradition and modernity. The odalisque herself—neither docile nor eroticized in the nineteenth-century manner—embodies autonomy and self-possession. Her gaze, though not directed outward, conveys quiet presence. The painting thus becomes a meditation on the harmony of figure and environment, of sensuality and abstraction. The bright orange underfoot can be read as a symbolic foundation of passion or vitality, while the cool grid suggests order and structure—together representing the balance between emotion and restraint.

Emotional and Psychological Impact

Beneath its decorative surface, Reclining Odalisque exudes a palpable emotional presence. The figure’s relaxed posture and the soft modeling of her flesh invite intimacy, yet the orthogonal grid and bold color bands impose a dignified formality. This tension between sensual ease and structural clarity creates a complex psychological atmosphere: one of serene contemplation tinged with underlying vitality. The neon-green grid lines, almost like silent trumpets, vibrate with latent energy, while the orange foreground radiates warmth. Viewers may feel both calm and invigorated, caught between repose and the electric pulse of modern life. In this way, Matisse transforms a depiction of leisure into a dynamic emotive experience.

Placement in Matisse’s Oeuvre

Reclining Odalisque stands at a decisive moment in Matisse’s career. It follows his decorative interiors of the early 1920s—marked by patterned screens and flattened perspective—and anticipates the radical cut-outs of the 1940s, where figure and décor would be distilled to pure shape and color. The painting’s bold brushwork and grid background resonate with his 1916–17 odalisque series, yet the neon shimmer and impasto texture push further toward abstraction. In terms of scale and ambition, Reclining Odalisque rivals earlier monumental works like The Joy of Life, but it channels that energy into a singular, streamlined figure rather than a multicharacter ensemble. As such, it exemplifies Matisse’s ongoing quest to reconcile representational figuration with the decorative and abstract potential of color and form.

Influence and Legacy

The formal innovations of Reclining Odalisque—its flattened space, grid pattern, and expressive impasto—have reverberated through twentieth-century art. Abstract Expressionists admired the autonomy of color and brushwork, while Color Field painters drew on Matisse’s use of nonrepresentational planes. The grid motif foreshadowed Minimalist and Op Art explorations of geometry, and contemporary figurative artists continue to reference the painting’s balance of sensuality and structure. Additionally, Matisse’s reimagining of the odalisque theme influenced later generations seeking to portray the female figure with both reverence and modernist freedom. Today, Reclining Odalisque remains a touchstone for how color, line, and surface can coalesce into a harmonious yet dynamic whole.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s Reclining Odalisque (1928) transcends the limitations of genre to become a landmark of modernist painting. Through its confident composition, radiant yet controlled palette, flattened pictorial space, and bold impasto, the canvas transforms a reclining nude into a unified tapestry of form and color. Matisse’s grid background and vibrant foreground strips both reference and subvert decorative traditions, while the odalisque’s serene posture and textured flesh assert human presence amid abstraction. As both a culmination of Matisse’s decorative experiments and a precursor to his late cut-outs, Reclining Odalisque affirms art’s capacity to harmonize figure and décor, emotion and structure, tradition and innovation. Over ninety years since its creation, the painting continues to captivate viewers with its timeless balance of sensuality and modernist rigor.