Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

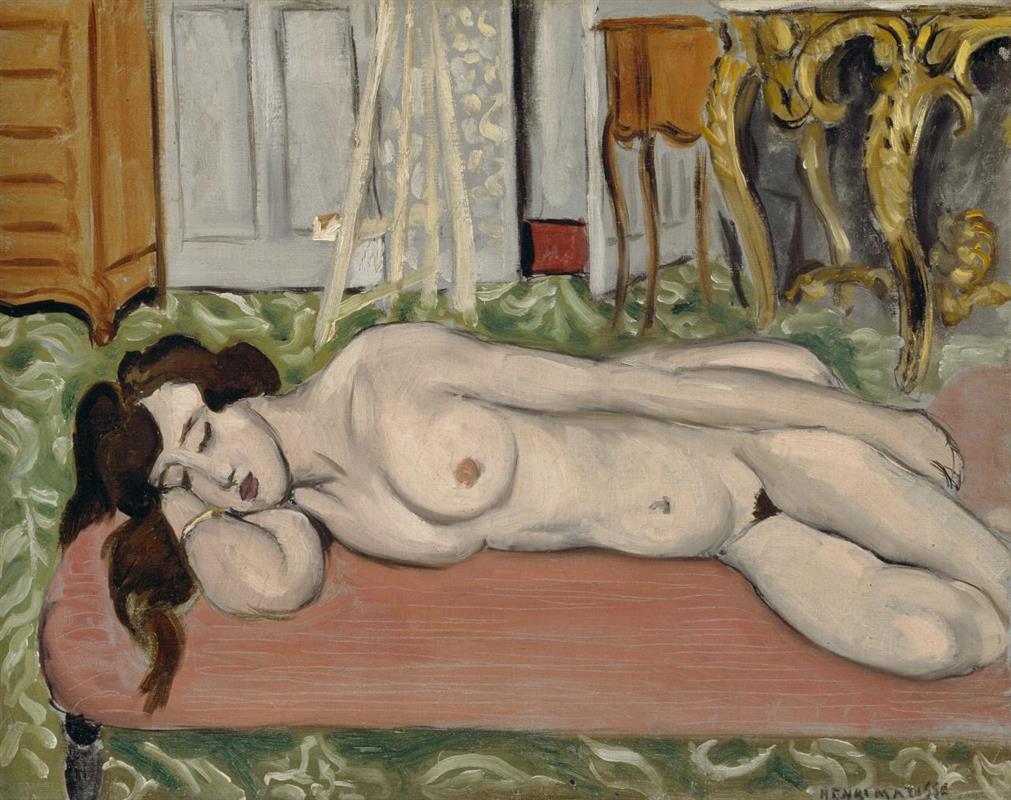

Henri Matisse’s “Reclining Nude on a Pink Couch” (1919) distills the modern odalisque to its essentials: a sleeping figure stretched along a low divan, a studio interior glimmering with patterned surfaces and rococo curves, and a color harmony that turns repose into radiance. The composition is intimate but never claustrophobic. The pink couch provides a warm stage; a green, leafy carpet flows like water around it; and behind the model a small theater of doors, easel, cabinet, and gilded table establishes the room as a working studio rather than a fantasy boudoir. With a few decisive lines and tempered tones, Matisse creates a nude that is as much about painting’s construction—color, contour, rhythm—as it is about sensual presence.

Historical Context

The year 1919 sits at the beginning of Matisse’s Nice period, when he returned to the Mediterranean after the First World War and made interiors, odalisques, and patterned rooms the core of his practice. The postwar context matters. Rather than depicting triumphal public scenes, Matisse explored private spaces that could hold calm after upheaval. The odalisque—long a Western image of leisure and display—becomes for him a studio subject in which color, craft, and concentration replace spectacle. In this canvas the model rests on a simple couch, the studio’s furniture is plainly visible, and the artist’s easel rises like a quiet signature in the background. The result is an art-about-art image: a modern nude built inside the site of its making.

The Motif And Pose

The figure lies along the couch with her head propped on one forearm and the other arm extended toward the thigh. Her knees are slightly drawn, establishing a gentle S-curve from hair to heel. The head tilts into sleep, lips closed, hair pooled against the forearm. The pose recalls Titian and Ingres yet is stripped of the pomp that often surrounds reclining nudes. Matisse’s model is neither a goddess nor a courtesan; she is a body at rest in a painter’s room. The feeling is not theatrical seduction but trust and repose. The gestures are modest and believable, allowing the picture’s structure—its color fields and arabesques—to carry the drama.

Composition As Stagecraft

Matisse designs the composition like a shallow stage. The couch runs horizontally across the lower third of the canvas, anchoring the figure and dividing the green floor from the paler wall. The background is set with verticals and diagonals: an orange cabinet at left, paneled doors at center, the pale tripod of an easel, a small side table, and a gilded console whose curling legs echo the leaf forms in the carpet. These objects do not clutter the scene; they serve as counters to the long horizontal of the body. By arranging the room as a series of blocks and arabesques, Matisse gives the reclining form equilibrium, so the eye moves between human curve and studio architecture without strain.

Color Harmony: Pink, Green, And Gold

The painting’s color is both restrained and sumptuous. The couch is a muted salmon pink, brushed in parallel lines that signal the upholstery’s ribbed fabric. Around it flows a green carpet animated by pale, curving leaf shapes that seem to ripple like water. This pink–green opposition—warm against cool—sets the body aglow. Flesh tones are kept light, hovering between warm ivory and a cooler gray-pink; the shadow tones remain gentle to preserve the sensation of diffused Mediterranean light. In the upper right, the gilt console injects flashes of yellow and black, a decorative fanfare that prevents the palette from drifting into pastel languor. The orange cabinet at left offers a second warm accent, while the pale panels of the doors calm the center. These relationships create a chromatic equilibrium that feels at once domestic and celebratory.

Line And The Living Contour

Contour is the armature of the painting. A single, confident line runs along the back, tucks at the waist, and slips over the hip; another defines the forearm, wrist, and hand pressed beneath the cheek. These lines swell and thin, never mechanical, giving the figure a pulse. In places the line opens, allowing the flesh color of the figure to meet the couch’s pink without hard separation, an approach that keeps air between forms. The gilded table and the carpet’s leaf motifs are drawn with the same calligraphic energy, so that furniture and pattern feel alive, not dead props. This unifies the room: everything is made of the same vibrant drawing, whether body, couch, carpet, or console.

Light And Surface

The light is even and quiet, the kind that comes from high windows or an overcast noon near the sea. There are no dramatic cast shadows. Instead, Matisse modulates planes with temperature shifts: a cooler gray along the flank, a warmer note across the shoulder, a faint blush above the knee. The paint sits thinly in some passages so the weave of the canvas participates, particularly in the doors and wall; elsewhere, as in the gilt console and the leaves of the carpet, the paint thickens into raised strokes. This modulation keeps the surface varied and tactile, reinforcing the sense that the studio is a place of real materials—wood, fabric, gold leaf, skin—rendered by a hand that enjoys their differences.

Space And Depth

The composition is shallow by design. The couch occupies the foreground; the model’s body runs parallel to the picture plane; and the wall, doors, and furnishings create a backdrop pressed close behind. The easel’s diagonal legs produce a hint of recession, and the small table’s top tilts slightly to suggest volume, but the overall effect is compressed, a modern space that respects the flat surface of the canvas. This shallowness intensifies intimacy. We do not peer across a cavernous room; we stand near the sleeper, granted proximity without intrusion.

Studio Truths

One of the painting’s pleasures is its frank declaration of the studio. The easel rising behind the model acknowledges the act of painting. The cabinet at left and the stool or side table at center-right register as useful, not purely ornamental. Even the gilded console—so flamboyant in its scrolling legs—reads less as palace furniture and more as an object found and enjoyed for its voluptuous line. Matisse shows the tools and toys of his craft without apology. The nude belongs to this working world rather than to a mythic harem. The effect is to humanize the odalisque tradition and relocate it in the modern studio, where making art and arranging life are intertwined.

Decorative Intelligence

Matisse’s decorative intelligence is everywhere. The green carpet’s pale, wave-like motifs rhyme with the carved volutes of the gilded table. The ribbing of the couch echoes the parallel brushstrokes in the walls and doors. The model’s hair, painted in rich brown curves, participates in the same arabesque language as the furniture. This web of echoes makes the composition coherent. Decoration is not an overlay but a skeleton that supports space and distributes attention. The eye can travel by ornament from couch to carpet to console and back to the body, always finding a familiar curve or repeat to hold onto.

Eroticism, Dignity, And Sleep

The figure’s sexuality is present but not sensationalized. Sleep softens display; the prone posture is a gift of trust rather than an invitation to conquest. The face, with closed eye and relaxed mouth, contains no theatrical expression, and the body, although carefully described, is not polished to porcelain. Slight irregularities—the natural weight at the hip, the gentle slack of the resting arm—preserve dignity and reality. This blend of eroticism and decorum is essential to Matisse’s Nice period: the body is an instrument for color and line, but it remains a person’s body, attended with respect.

The Pink Couch As Emblem

The couch is more than furniture; it is a pictorial device that shapes the painting’s mood. Its low height and soft color create a platform of warmth on which the body floats. The ribbed texture, made by lightly dragged, parallel strokes, adds a steady tempo beneath the more fluid rhythms of the figure. Because the couch is neither dark nor gaudy, it never competes with the skin tones; instead it amplifies them, the way a good accompanist supports a soloist. Across Matisse’s work, couches, daybeds, and carpets become recurring instruments in the orchestra of pattern; here the pink couch is the key of the piece.

The Green Carpet And Sense Of Climate

The carpet’s green is not a neutral floor; it is the painting’s air made visible. Its coolness brings the sensation of a sea breeze into the room, and its leaf-like swirls supply a vegetal counterpoint to the warm couch and body. The pattern avoids perspectival tiling; instead it flows up the picture plane, flattening stretch of floor into a decorative field. This maintains the painting’s modern shallow space and supports the feeling of Mediterranean climate—a soft, maritime mildness that bathes everything evenly.

The Gilded Console And The Language Of Curves

The rococo console on the right, with its golden scrolls and leafy feet, is a small fireworks of line. Its curvilinear energy amplifies the arabesques of the model’s form and the carpet motifs. It also injects a subtle note of play, a reminder that Matisse delights in objects not for their status but for their visual music. The lively console prevents the quiet of the sleeping figure from dissolving into monotony; it supplies a sparkling counter-theme that keeps the composition dancing.

Modeling Without Illusionism

Matisse avoids classical modeling built from detailed shadow and highlight. Instead, he suggests form through junctions of color and temperature. The breast is understood by a soft, cooler crescent; the abdomen rounds where warm and cool flesh tones meet; the shoulder turns with a single broad stroke. This economy allows the viewer to complete volumes imaginatively. The method is modern not because it rejects reality, but because it trusts that a few well-placed notes can summon it.

Relations To Tradition And To Matisse’s Own Work

The reclining female nude has a long lineage, but Matisse modernizes it by routing emphasis away from narrative and toward pictorial construction. Ingres’ odalisques provide a precedent for languor and contour, yet Matisse strips away the polished finish and packs the background with studio facts. Compared to his earlier, hotter Fauvist canvases, the palette here is tempered; yet the independence of color remains intact—pink couch and green floor do not imitate “local” color so much as create harmony. The picture also anticipates the later odalisques of the 1920s, where patterned textiles and shallow rooms become theaters for chromatic pleasure. It stands as a bridge: traditional genre, modern means.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Path

The eye follows a deliberate route. It begins at the dark arc of hair and the closed eyelid, glides along the shoulder and back, finds the inflection at the hip, and travels to the slightly bent knees. From there, the pink couch lines pull the gaze left to right, and the green waves of the carpet lift the eye back into the background where the pale doors and easel create a resting zone. The gilded console draws the attention again to the right edge, and the circuit returns to the sleeper’s face. This path is unhurried and circular, echoing the painting’s theme of calm, continuous rest.

Material Presence And The Ethics Of Touch

Because the paint remains visible as paint—thin here, thicker there—one senses the ethics of touch at work. Matisse’s handling of the body is gentle but not precious, and his handling of furniture is loving but not fetishistic. The same hand that draws the console’s flourish draws the curve of the rib and the roll of the couch. This parity dignifies the subject and the studio alike. All elements are worthy of attention, and attention is the currency that gives them life.

The Feeling Of Time

Although the model sleeps, the painting is not frozen. The rippled brush of the carpet, the soft striations of the couch, and the flicker of highlights on the gilt suggest slight currents of air and the subtle settling of a body in rest. The easel in the background hints that this moment belongs to an ongoing practice—the hours of a working day in which model and painter share quiet endurance. Time here is not narrative sequence but duration, the kind of time that painting is uniquely suited to hold.

Conclusion

“Reclining Nude on a Pink Couch” offers a concentrated statement of Matisse’s art at the start of the Nice period. It translates an old subject into a modern language of shallow space, living contour, and tuned color. The pink couch and green carpet establish a harmony that sets the figure aglow; the studio furnishings acknowledge the truth of making; the decorative rhythms bind room and body into a single orchestration. The painting’s sensuality is calm rather than clamorous, its intimacy founded on respect, and its beauty inseparable from its construction. In a world recovering from war, Matisse found in this room a durable pleasure: the quiet music of a body at rest, a studio at work, and color breathing across a canvas.