Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

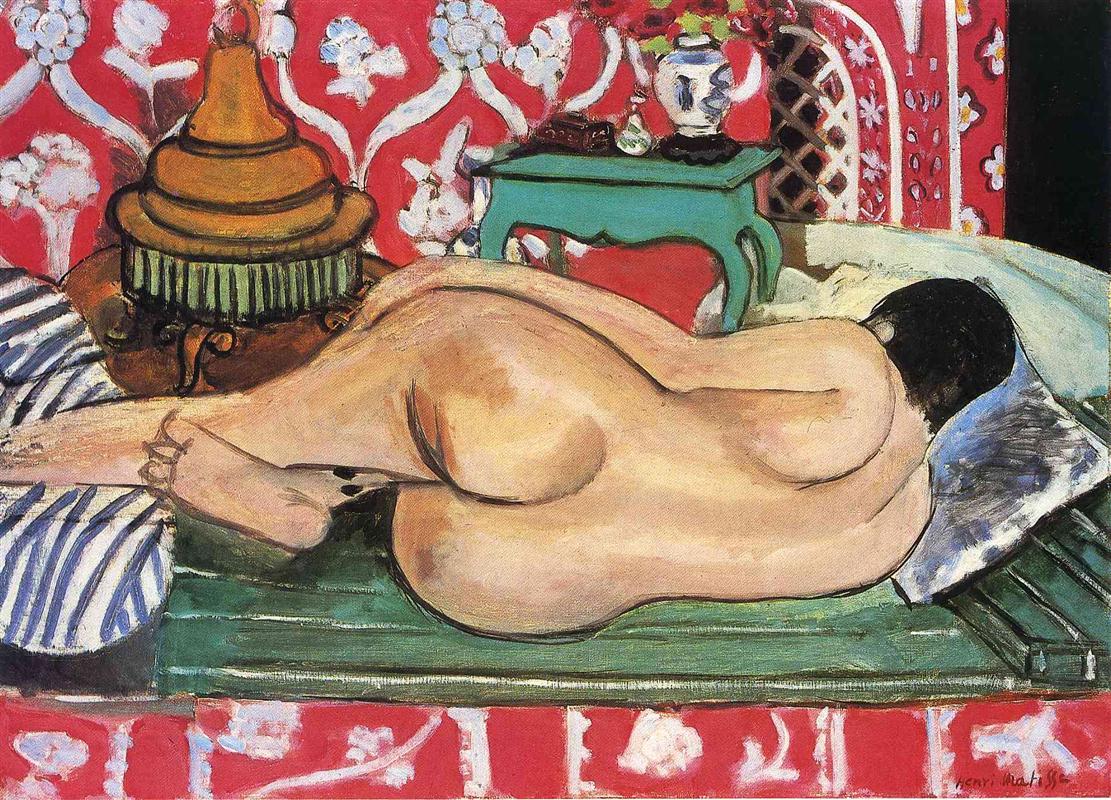

Henri Matisse’s “Reclining Nude, Back” (1927) condenses the ambitions of his Nice period into a single, resonant chord of color, pattern, and pose. A nude figure stretches horizontally across a low green divan, her back turned to the viewer, head pillowed at the right edge, feet drawn up to the left. The surrounding room is a theater of textiles: a red wall stenciled with white vegetal arabesques; a turquoise side table carrying a vase of flowers and a small box; a striped cushion; and the familiar brass vessel that punctuates so many of Matisse’s interiors. The composition is intimate yet assertive. Rather than narrate an exotic scene, the painting demonstrates how a reclining body can anchor a decorative architecture, how pattern can meter time, and how warm and cool colors can be tuned until they breathe together.

The Nice Period As A Laboratory Of Color And Calm

By 1927 Matisse had transformed the explosive chords of Fauvism into a modern classicism based on interval and relation. Working in sunlit studios in Nice, he staged rooms with portable furniture, screens, and patterned fabrics, inviting models to inhabit poses calibrated for clarity and rest. The odalisque motif supplied a permissive framework for languor and textile abundance without obliging anecdote. In this canvas, the model’s back becomes the quiet axis around which the room turns. The goal is neither erotic display nor ethnographic description; it is a rigorous, pleasurable order in which the decorative does the structural work of painting.

Composition As A Horizontal Sentence

The composition reads like a long, horizontal sentence with carefully placed punctuation. The sentence begins at the pillow, where the dark oval of hair and a cool gray-blue slip create a soft comma, continues across the sprung arc of the back, slows at the hip’s turning point into a semicolon, and concludes in the intertwined feet at the left. Large still-life accents regulate the flow. The brass vessel occupies the far left like a golden clause; the turquoise table with its vase interrupts the upper register just beyond the hip. At the bottom edge, a red band patterned with pale plant-like forms brackets the space like an ornamental footer. The divan’s elongated green planks act as a staff on which the whole phrase is written. Everything is arranged to honor the body’s sustained curve while keeping the eye in motion.

Color As Architecture And Atmosphere

Color builds the room as surely as carpentry would. Red dominates the wall and lower border, setting a warm climate that could easily overheat. Matisse cools and mediates that heat with the green divan, the turquoise table, and the gray-blue pillow slip, while the brass vessel accumulates warmth into a single dense mass and the small black tabletop grounds the still life. Flesh tones are tuned to sit comfortably amid this alternation. The back is a spectrum of apricots, pinks, and pearly grays shifting with the angle of the plane; shadows are chromatic rather than black, moving toward olive near the waist, toward violet in the hollow at the shoulder. Because each color borrows slightly from its neighbors—the green of the divan warming near the hip, the red wall cooling in the proximity of white stencils—the palette breathes instead of shouting. Color here is not an accessory; it is the architecture of feeling.

Pattern As Structural Rhythm

Matisse’s patterns are not merely decorative; they are the metronomes that pace the surface. The wall’s white stencils repeat at an even cadence across the red field, establishing a steady, medium-tempo beat in the upper half. The floor or lower panel repeats the idea at a slower pulse, its motifs larger and more widely spaced. On the divan, directional marks and planked grooves introduce a quiet counter-rhythm that runs the length of the painting. The striped cushion near the feet translates the theme into black-and-white bars, a brief percussion passage that prevents the left side from dissolving into softness. This distribution of meters keeps the viewer’s attention moving without agitation, like an adagio with clear downbeats.

The Back As A Modern Motif

Turning the figure away from the viewer shifts the painting’s register from portrait to sculpture. The back is a classic subject in European art, but Matisse modernizes it by simplifying contour and letting color carry most of the modeling. The shoulder blades, spinal trough, and sacrum are indicated with tender economy. A few darker strokes along the edge of the waist and under the buttock are sufficient to flip the planes; the rest is achieved with temperature: warm planes facing the room, cooler ones relaxing into shadow. The result is intimate without vulnerability, sensual without melodrama. The back becomes a quiet emblem of rest, set against the livelier talk of fabrics and objects.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Edge

Matisse’s contour grants the picture its authority. The back’s long silhouette swells and thins with anatomical truth; the sharp turns at the ankle and heel are snapped into place with crisp, dark notes; the hand at the left foot is abbreviated to a few decisive angles that read instantly. Furniture and objects receive the same living outline. The brass vessel’s dome is a rhythmic curve rather than a mechanical arc; the table’s cabriole legs are elastic S-shapes that echo the figure’s broader sweep. These lines do not imprison color. They set a permeable boundary at which warm and cool can negotiate, letting the room feel both graphic and atmospheric.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The light in the painting is even and reflective, typical of the Nice interiors. Rather than a single spotlight, illumination seems to circulate, bouncing off the red wall and green divan. Shadows are therefore chromatic and thin. Along the lower back, a cool ash-gray meets a warmer ochre in a soft gradient; beneath the arm and along the ribs, violet and olive participate without deadening the color. Highlights are small but exact: a milky touch on the shoulder, a bright gleam on the brass, a white kiss on the vase. Because value contrasts are moderated, color remains sovereign, and the atmosphere stays gentle and breathable.

The Brass Vessel, Table, And Vase As Countermelodies

The large golden vessel at the left is not only a visual weight but a counter-melody in the composition. Its stacked tiers echo the sequence of shoulder, hip, and feet; its warm ochres and greenish shadows multiply the room’s dominant red into a family of related temperatures. The turquoise table mediates between the brass and the flesh, offering a cool platform on which the small still-life—white vase with a spray of flowers and a dark box—adds high notes of white and black to the chord. By placing these vertical accents above the back’s long horizontal, Matisse gives the body a dignified accompaniment. They keep the eye from sliding off the curve and lead it gently back across the surface.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

While overlaps and cast shadows give us enough depth to be persuaded—the vase sitting on the table, the brass resting on the rug, the body indented into the cushion—the general effect is intentionally compressed. The wall behaves like a tapestry close behind the figure; the lower band rises as if pinned along the bottom edge; the divan is a shallow shelf. This productive flatness focuses attention where Matisse wants it: the surface where pattern meets contour and color meets color. The painting is not a window into another room; it is a modern interior arranged as a breathing, legible plane.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse often likened painting to music, and this canvas is best read as a score. The red wall’s even motifs provide the tempo; the green divan offers a sustained middle register; the brass and table strike resonant chords at measure points; the back sings the melody—one long, unbroken phrase that invites the viewer to breathe with it. The eye loops in composed circuits: pillow to shoulder, shoulder across the back to hip, hip to vase, vase down the table leg to the divan’s edge, divan along the striped cushion to the feet, and back again to the brass. Each loop reveals small consonances—a white stencil aligning with a shoulder highlight, a green reflection touching the lower back, a black table top repeating the hair’s tone. Because the relations are distributed rather than centralized, the picture supports prolonged attention.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

Despite saturated color and strongly stated pattern, the psychological tone is serene. The turned-back pose is self-contained; the head receives the pillow without strain; the weight of the body is felt in the gentle flattening of the hip against the cushion. Objects nearby—vessel, vase, box—do not crowd but companion the figure. The room’s warmth is profound but controlled; blues and greens temper the red so that the eye is bathed rather than flooded. For the viewer, the experience is hospitable: one can return daily and discover new hinges among hues and shapes without exhausting the image.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Reclining Nude, Back” speaks to many works from 1925 to 1927. It shares the diamond or stencil walls and brass accents of several odalisques, yet its emphasis on the back places it near Matisse’s sculptural sensibility, recalling his bronzes where the arc of spine and pelvis is paramount. Compared with “A Nude Lying on her Back” of the same year, which stages a diagonal figure within a blue-latticed red wall, this canvas opts for a fully horizontal body and a broader, more ornamental field. Compared with “Odalisque by the Red Box,” it replaces a small, centralized accent with two larger anchors—the brass and the table—that bookend the body. In each case, the constants prevail: shallow space, living contour, and color that carries structure.

Tactile Intelligence And The Evidence Of Touch

Material differences are conjured by touch rather than description. The back is laid with smooth, creamy strokes that let the paint’s skin read as skin; the divan’s green planks are brushed with more resistance, so the grain of canvas participates and suggests textile nap; the brass is built with thicker, slightly sticky marks that catch light like metal; the wall’s stencils are quickly swiped, leaving edges that breathe. Pentimenti remain visible: a softened outline at the waist, a repositioned contour along the feet, a corrected border on the turquoise table. These traces make the calm we feel credible; harmony has been achieved through revision, not formula.

The Ethics Of Ornament And The Modern Interior

The historical odalisque risks exoticism, but Matisse’s distribution of dignity neutralizes that hazard. The human figure, the vessel, the table, the wall, and the patterned textiles are granted equal clarity of attention. Ornament is the method, not the subject. It orders the plane, clarifies pace, and makes the room a generous place for the gaze to rest. The result is a form of modern classicism in which pleasure and discipline coexist: strong color is spaced, pattern is metered, and calm is earned.

Why The Painting Endures

The painting endures because its satisfactions are structural and renewable. Each viewing yields a fresh hinge of relation: a pale blue from the pillow surfacing in the white stencils; a green reflection touching the lower spine; a small red echo from the wall warming the hip; a black repetition linking the hair, the tabletop, and the line defining the divan’s edge. No single effect exhausts the image because the work’s rightness rests on a network of tuned intervals. You can linger, leave, and return to find the harmony intact and welcoming.

Conclusion

“Reclining Nude, Back” is a compact manifesto of Matisse’s Nice-period ideals. A single, unbroken figure lies across a shallow interior where a red patterned wall, a green divan, a turquoise table, and a golden vessel converse like instruments in a chamber ensemble. Color behaves as architecture; pattern is a disciplined rhythm; contour is a breathing edge; light is chromatic. The image invites patient looking and rewards it with steady, replenishing calm. In a century of noise, Matisse offers a room where attention can slow without losing alertness, and where beauty is not a flourish but a rigorously spaced condition.