Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

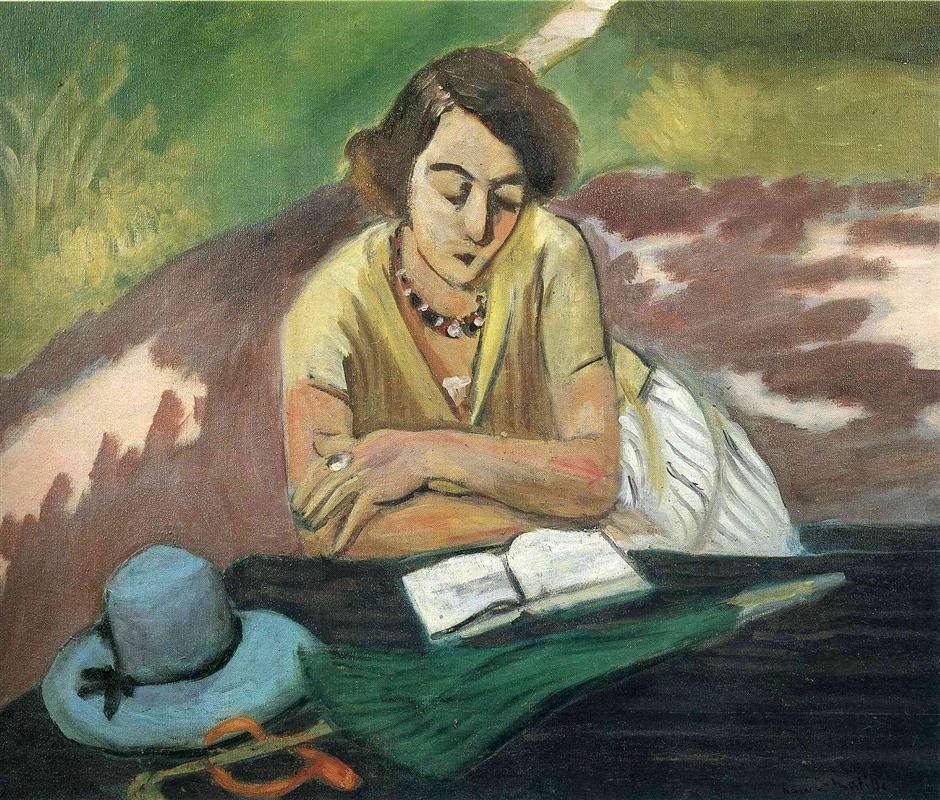

Henri Matisse’s “Reading Woman with Parasol” turns a casual moment of concentration into a complete weather system of color, touch, and tempo. A young woman leans over a small open book, elbows folded on a dark tabletop. A light blue hat rests nearby; a green parasol stretches diagonally across the foreground like a quiet metronome; a pair of amber spectacles peeks from under the brim. Behind her, a softly rolling landscape—patches of green, clay, and cream—breathes like clouds over ground. Nothing in the image is theatrical, yet the scene feels charged, as if the air were tuned to the frequency of reading. Matisse builds this charge not through detail but through relations, letting color and contour do the work of narrative so the viewer senses time slowing around the act of attention.

A Nice-period meditation on leisure and looking

Painted in the Nice years, this canvas belongs to Matisse’s sustained exploration of modern classicism: figures set in lucid spaces where pattern and color provide architecture and mood. Instead of a grand interior or a patterned screen, he chooses a simple outdoor or terrace setting and scales the drama down to the near field. The subject is not the book’s story but the human state of reading—head bowed, shoulders released, features softened into thought. The parasol and hat suggest an errand briefly suspended; the spectacles imply the mechanics of seeing laid aside for the pleasure of unmediated concentration. Matisse treats these props as equal partners with flesh and ground, transforming a pause into an atmosphere.

Composition led by diagonals and resting ovals

The composition is a choreography of diagonals anchored by rounded forms. The green parasol, placed low and left-to-right, establishes the principal vector. The woman’s forearms cross in a counter-diagonal that both contains and echoes the parasol’s thrust. Her head, bent forward, creates a stable oval that locks the upper triangle of the composition, while the hat forms a second oval at the lower left, balancing the mass of the figure. A pale path in the background runs from top center toward the figure’s crown, a visual whisper that the world continues beyond the frame even as the mind narrows its focus. These few structural lines allow the eye to circle the center—hat to parasol to book to face—without ever being trapped.

Color climate: olive, citron, clay, and sea-air blue

Matisse’s palette here is gentler than in his odalisque interiors but no less deliberate. The woman’s blouse is a soft citron yellow that glows against the cooler greens of grass and parasol. Her skirt picks up the light in chalky whites and pale greys; the tabletop is a charcoal violet that absorbs brightness and concentrates the scene. The hat’s sea-air blue is more than accessory: it cools the lower left and prevents the yellow blouse from overheating the picture. In the background, a band of sap green slides into a clay-brown zone mottled with cream, like light skimming over uneven terrain. Flesh tones—a warm rose-ochre carried into quieter greys on the shadowed cheek—sit in the middle of the chord, harmonizing hot and cool. Nothing is overly blended; small temperature shifts replace heavy modelling so the surface stays breathable.

Drawing that conducts, not cages

The contour in this picture is the work of a confident conductor. Around the arm and wrist, the line darkens slightly to keep the yellow sleeve from dissolving into the table. At the face, the line thins and sometimes gives way to a meeting of values—shadow to cheek, hair to forehead—so the visage remains tender and permeable. The parasol’s rib is a simple stripe, firm enough to guide the diagonal but not so heavy that it feels mechanical. The folded book is briskly drawn: two planes and a hinge are all that’s needed. The spectacles are described with a few loops of amber paint, their cartoon-like simplicity reinforcing the sense that the painting values clarity over pedantry. Matisse uses line where structure must hold and lets it evaporate where air and light should pass.

Brushwork that keeps the moment alive

Look closely at the background and the blouse. The ground is laid with open, scumbled strokes that let earlier layers breathe through; these strokes pivot in direction so the land seems to turn under light. The blouse is handled in wider, buttery passages that catch at the seams, suggesting folds without counting them. Hair is a series of soft, directional swipes that both model plane and cue the tilt of the head. On the tabletop, darker paint is drawn across the grain, leaving faint tracks; the effect is not polished furniture but a serviceable surface that absorbs the reader’s world. Everywhere, Matisse stops as soon as a passage “reads,” keeping the painting nimble, as if the woman might lift her eyes from the page at any second.

The parasol as visual and symbolic hinge

The green parasol is the painting’s hinge. Formally, its diagonal organizes the foreground and gives the static act of reading a dynamic counterweight. Chromatically, its cool green mediates between the warm blouse and the warm-brown earth, making the mixed palette cohere. Symbolically, the parasol speaks of a life lived in light—an object for strolling, for shade, for cultivated leisure. Placed next to a book, it quietly proposes a modern ideal: a day divided between movement and repose, weather and text. That ideal animates much of Matisse’s Nice period, where comfort is not decadence but a rhythm that protects attention.

A portrait of absorption without psychological fuss

Matisse refuses melodrama yet grants the sitter interiority. The mouth relaxes, the lids are heavy, the chin tilts into the shelter created by the arms. The necklace—a string of warm beads and a pale pendant—rests on the clavicle like a metronome stilled. The ring on the forefinger is the tiniest bright accent, acknowledging the hand’s role as both support and potential page-turner. We do not know what she reads, and the painter doesn’t tempt us with legible words; the book’s whiteness is a mirror for her attention. By withholding anecdote, Matisse allows the universal to surface: the pleasure of being briefly nowhere except inside a sentence.

Space built from stacked, breathable planes

Depth is managed through overlapping fields rather than strict perspective. Foreground: the dark table and the clutch of objects. Middle ground: the figure, elbows resting, torso advancing into our space. Background: a belt of mixed tones that reads as terrain, its mottling and path-line hinting at recession. Because each plane retains visible brushwork and color variation, none of them feel like stage flats; they are permeable, admitting air. This stacking lets the viewer inhabit the space while remaining fully aware that it is paint doing the work.

Light distributed by value relations

There is no single dramatic light source. Illumination is a network of value relationships. The blouse’s upper surfaces brighten against the table’s darkness; the cheek turns cool where it meets the shadow beneath the brow; the hat’s crown picks up a matte highlight that makes its felt plausible; the parasol gleams in places where a stroke of lighter green rides along a darker one. The background’s lightest path passes behind the head, giving a faint halo that lifts the profile without resorting to outline. Because light is relational, the painting remains convincing even as it stays simplified.

Objects as character clues and chromatic anchors

Every object earns its place. The blue hat cools the picture and suggests modest urbanity. The green parasol, beyond its compositional role, points to outdoor sociability. The amber spectacles nudge the scene toward intimacy; they have just been removed, implying that the act of reading has shifted from duty to pleasure. Even the necklace, with its red-brown beads, carries color from earth to skin, ensuring that the figure doesn’t float free of her setting. The book, an open whiteness, is both literal and abstract—the brightest plane at the center of the picture’s attention.

Affinities and contrasts with Matisse’s reading images

Matisse painted readers in interiors, on sofas, by windows. Compared with those works, this painting is stripped down—no patterned screens, no striped cloths, no crowded still lifes. The reduction focuses the eye on the mechanics of attention: head tilt, elbow crossing, the nearness of objects essential to an afternoon outdoors. Where some Nice interiors rely on spectacle—saturated blues and reds, buzzing patterns—“Reading Woman with Parasol” trusts tonal modulation and a breezier palette. It is the same aesthetic of ease, translated to a terrace or garden.

The viewer’s path through the scene

Most viewers enter through the face, where small contrasts concentrate: dark hair against light path, warm cheek against cooler shadow. From there the gaze drops to the book, slides along the crossed forearms, and glides onto the parasol’s shaft toward the hat and spectacles. The eye then lifts into the background’s mottled greens and clays before circling back along the pale path to the head. Each lap reveals subtle episodes: a violet edge where sleeve meets table; a soft green reflection lifting into the blouse’s shadow; a single brighter stroke on the parasol tip that pins it to the world; the way a pinkish brushmark at the elbow echoes the necklace’s warmth. The picture is designed for this kind of revisiting; it sustains attention the way the woman sustains her reading.

Sensation over description

The painting persuades by sensation rather than by literal description. Background vegetation is not botanically named; it is a set of tonal swells that feel like shade patches and sunlit turf. The tabletop is not grained wood; it is a dark field whose weight we accept because of how it receives the objects. The blouse is not silk or cotton by label; it is airy because edges are soft and internal modelling stays transparent. This economy honors the viewer’s perceptual intelligence and keeps the image from congealing into illustration.

The ethics of ease

Matisse’s oft-quoted wish that art provide a calming influence is not shorthand for escapism here. Ease is the outcome of accurate relationships: the weight of the table against the lift of the path, the cool hat against the warm blouse, the diagonal parasol against the vertical spine. The painting proposes a humane tempo for looking—unhurried, clear, generous—mirroring the sitter’s own chosen tempo. In a world that often celebrates agitation, this maintenance of calm attention is both aesthetic and ethical.

Why the image endures

“Reading Woman with Parasol” stays with us because its parts click into place with quiet inevitability. The figure’s diagonal elbows, the parasol’s echoing line, the hat and spectacles as friendly anchors, the book’s white at center, the soft path behind the bowed head—each element supports the others without noise. The work offers renewable pleasures: the discovery of a cooler seam along the forearm, the exact value of the hat’s highlight, the tiny amber loop of a spectacle arm against blue felt, the faint green echo inside the book’s shadow. These are not decorations; they are the small guarantees that the moment has been understood.

Conclusion

In “Reading Woman with Parasol,” Matisse refines his Nice-period language to an intimate scale. Color sets the climate, line conducts the eye, brushwork keeps the air moving, and a few chosen objects act as companions to thought. The painting does not tell a story about who the woman is or what she reads; it shows, with tender clarity, what it feels like to inhabit a pocket of concentration in an afternoon’s light. That sensation—of attention made visible—explains why the canvas remains as fresh as the parasol’s green and as calm as the book’s blank, bright page.