Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

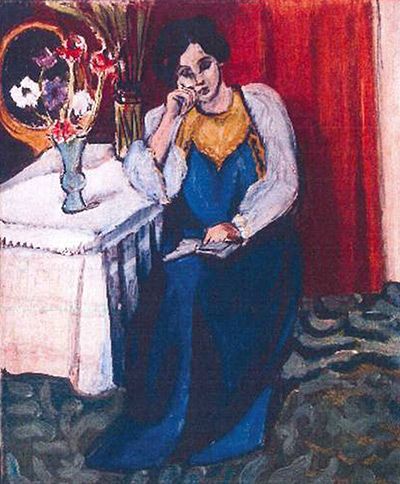

Henri Matisse’s “Reading Girl in White and Yellow” (1919) stages a concentrated moment of interior life. A young woman sits beside a small table, a book open in her lap, fingers brushing her cheek as if to hold a thought in place. A vase of flowers lifts a bright counter-melody on the tabletop, a round mirror catches a pocket of light, a red curtain presses forward like a theater drape, and a patterned green floor flows under everything like quiet surf. The picture is intimate without becoming sentimental, decorative without surrendering to ornament for its own sake. It announces the Nice period’s concerns—light, pattern, repose—while retaining the structural discipline that keeps Matisse’s calm from turning static.

Historical Context

Painted the first year after the Armistice, the work belongs to a moment when artists in France were rediscovering the consolations of interiors, private rituals, and measured light. Matisse had begun to make Nice his home base, gravitating toward seaside rooms where doors and curtains negotiated between indoor life and marine air. The figure of a reader appears throughout his career, but in 1919 the motif carries the special charge of recovery: quiet time restored, attention reclaimed from public catastrophe. “Reading Girl in White and Yellow” converts that cultural longing into a domestic image that honors slowness, reflection, and the life of the mind within a decorative setting.

Subject And Pose

The young woman is seated three-quarter to the viewer, her torso slightly sloped, her left hand cupping cheek and temple while the right hand supports or turns a page. Her dress is a deep oceanic blue trimmed by white sleeves and a yellow panel at the bodice; the garment’s color blocks do as much compositional work as the figure’s contours. The head tilts without theatricality; the eyes drop just beyond the page, suggesting that she is reading and thinking at once. The pose is not a frozen tableau but a sustained action—reading as a kind of breathing. The leaning elbow and propped head mark the body’s effort to hold steady while the mind moves.

Composition As Architecture

Matisse organizes the room with a small set of powerful shapes. The table is a bright, near-rectangular slab with a fringe of cloth; the red drape descends as a broad vertical plane; the mirror is a golden disc; the floor is a soft sea of patterned green; the figure’s blue silhouette occupies the center like a keystone. These elements interlock to produce a shallow yet convincing space that reads less as an “interior view” and more as a harmonized arrangement of planes. The book operates as a compositional hinge: a small pale rectangle whose diagonals echo the elbows and keep attention tethered to the figure’s task.

Color Harmony: Blue, White, Yellow, Red, Green

The palette is carefully tuned. The cool depth of the dress stabilizes the image, its dark blues absorbing the red of the curtain and the saturated greens below. The white of the sleeves and tablecloth injects light without glare; it is the picture’s breathing room. The yellow panel at the bodice is crucial: it mediates between the warm red and the cool blue, and because it sits where heart and lungs would be, it gives the figure a warm center. The floor’s green—patterned with pale curls—adds climate and calm; it keeps the reds from overheating and prevents the whites from floating away. Nothing is excessively saturated; the harmony is measured like chamber music.

Drawing And The Living Edge

Contour is the painting’s secret skeleton. Matisse’s line swells and loosens around the figure’s shoulders, tightens at the elbows, and quickens at the fingers that touch cheek and page. The line around the table is steady and slightly irregular, preventing the plane from becoming mechanical; the curls on the carpet are sketched rather than engineered, their openness preserving the sense of air moving underfoot. Even the flowers in the vase are drawn with speed—a few elastic strokes that state stem and petal without pedantry. Everywhere the line declares that this is paint on canvas, not a masquerade of photographic precision, and that truth gives the scene its humane warmth.

Light And Atmosphere

The light in this canvas is diffuse and interior, more like the consistent glow of a cloudy day than the sharp drama of a spotlight. The whites are creamy rather than icy; shadows are warm and thin; the red curtain holds light rather than swallowing it. The mirror may reflect the window, but Matisse refuses literal specularity; instead he uses the mirror as a golden node, a gentle lamp within the picture that keeps the upper left corner alive. The overall effect is of time paced by reading rather than by clocks: a long, elastic hour during which light barely shifts.

Pattern As Organizing Thought

Pattern in Matisse is never mere decoration. Here the carpet’s leafy scrolls, the fringe of the tablecloth, and the small blossom shapes in the vase compose an ornamental rhythm that binds the room. Each pattern is scaled to its role: the carpet broad and rolling, the cloth’s edge a tight, saw-tooth cadence, the flowers quick flares. The blue dress, largely unpatterned, becomes the necessary counterform—the quiet field against which the ornamental voices can play. Pattern streams through the image the way a theme moves through a sonata: sometimes foregrounded, sometimes supporting, always organizing feeling.

The Table, Vase, And Mirror

The left side of the painting offers a still-life within the figure study. The white tablecloth, with its neat fringe, signals domestic order. The vase, pale blue with scarlet and cream blossoms, introduces vertical accents that counter the reader’s bowed head and the long downward sweep of blue dress. The round mirror is a brilliant compositional invention. It acts like a sun—golden, circular, radiating a soft aura—while slyly acknowledging that this is an interior where seeing and being seen matter. The mirror’s placement also pulls the eye back into the left half of the picture so that attention doesn’t settle exclusively on the figure.

Gesture Of Reading

The most expressive element may be the hand at the cheek. It is a familiar human gesture—part concentration, part comfort. The elbow plants near the table edge as if to connect thought to the stable world of furniture and floor. The other hand’s engagement with the book suggests movement through time: a page about to turn, a paragraph just finished. Because the face is not minutely detailed, the hands carry psychological weight. They keep the reading from becoming an illustration and turn it into a felt, bodily activity.

Space And Depth

Space is shallow but persuasive. The carpet rises up the picture plane, flattening the floor into a decorative field; the curtain reads as a sheet pinned to the wall rather than as a deep recess; the table advances nearly to the plane of the picture. But overlap and scale are enough to cue depth: the table sits forward of the mirror; the figure overlaps the drape; the vase stands in front of its reflection. This measured shallow space is central to Matisse’s modernism. It preserves the painting’s surface harmony while granting just enough breathing room for the room to feel habitable.

Material Presence

Matisse’s paint handling is direct. The red drape shows the soft trails of a loaded brush; the carpet’s motifs are laid with visible bristles; the white cloth is a light scumble over darker underpaint that lets the weave flicker through. These textures are not demonstrations of craft for their own sake; they are sensations scaled to the objects they describe. The cloth looks soft because the paint is thin; the curtain feels plush because the paint is dragged; the flowers are fresh because the strokes are quick and wet. The viewer registers the studio’s material reality through the painting’s material honesty.

Dialogue With Tradition

The reading figure belongs to a long lineage from Dutch interiors to nineteenth-century intimism. Matisse recognizes that inheritance but remakes it for modern eyes. Where Vermeer builds space with calibrated perspective and minute effects, Matisse builds it with blocks of color and living line. Where nineteenth-century salon pictures might narrate the book’s contents through props or expressions, Matisse leaves narrative blank so that the act of reading itself—attention, absorption, the soft separation from the room—becomes the subject. The painting is not an anecdote; it is a condition.

The Ethics Of Looking

There is tenderness in the way Matisse locates the figure within the room. She is given privacy by the angle of her head and by the absence of any second gaze within the picture. The mirror faces away; the flowers look outward; the curtain shields the world. The viewer is close but not intrusive. This tone aligns with the broader ethic of the Nice period: the body and the interior are places for slow looking, not sites of conquest. The painting honors the woman’s attention by mirroring it—by attending with equal care to cloth fringe, carpet curl, and page edge.

Rhythm And Movement

Despite its quiet, the painting vibrates with rhythm. The red curtain’s vertical fall sets the tempo; the table’s diagonals create syncopation; the mirror’s circle offers a sustained note; the carpet’s pattern murmurs like accompaniment; the quick flicks in the vase are trills. The figure’s blue silhouette rides this rhythm like a melody line, rising and falling from shoulder to hem. The book is the pause mark—the fermata—under which time holds.

Color Psychology

The dominant blue of the dress carries emotional temperature: steadiness, depth, a mild melancholy held at bay by warmth. The yellow at the chest warms the center of the figure and links her to the mirror’s golden ring and the flowers’ bright cores. The red curtain suggests interior heat, but because it is balanced by blue and green, it doesn’t overwhelm. This equilibrium—cool intelligence, warm heart, sheltered fire—feels tailored to the act of reading, the joining of thought and body in a room that supports both.

Relations To Matisse’s Other Works Of 1919

This canvas connects to the contemporaneous balcony scenes and nudes through its devotion to thresholds and interiors. Like the balconies, it places a figure in relation to a vertical field of color; like the nudes, it trusts contour and large planes to carry form. But it also asserts a quieter register distinct from the odalisque’s sensuality: the sensual pleasure here is cognitive—the feel of paper, the weight of a paragraph, the dignity of attention. It is an important counterpoint in the year’s production, showing how Matisse’s decorative language could encompass different kinds of inwardness.

How To Look

A rewarding path through the picture begins at the mirror’s gold circle, drops along the vase into the white plane of the tabletop, catches on the reader’s propped elbow, slides to the hand and book, and then flows down the blue triangles of the skirt to the murmuring green floor. From there the eye rises up the red curtain and returns to the face. This circuit traces both the design and the action: light to object, object to hand, hand to thought, thought to body, body back to room. Each lap feels slower than the last, as if the painting were teaching the viewer to read it with the same patience the figure gives her book.

Meaning For Today

Contemporary viewers may find in this work a portrait of attention that feels rare and precious. The painting validates the ordinary heroism of focus in a distracting world. It suggests that a room can be a sanctuary for thought if its forms are tuned—table for grounding, color for warmth, pattern for gentle movement. It also reminds us that the most durable pleasures in art are often modest: a good chair, a good book, a patch of quiet light, a few flowers making color audible.

Conclusion

“Reading Girl in White and Yellow” is a studied celebration of an interior life. Through measured color, living contour, and a room orchestrated like chamber music, Matisse turns a private act into a shared experience of calm. The red curtain and green floor breathe around the blue figure; the white table and yellow bodice stabilize and warm; the mirror and flowers keep light circulating. Nothing shouts, everything participates. The painting offers a model for how attention and beauty can inhabit the same square meters—how a person, a book, and a room can coexist in a harmony that feels both modern and timeless.