Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Quiet Face, a Loose Blouse, and a Book Held Like Light

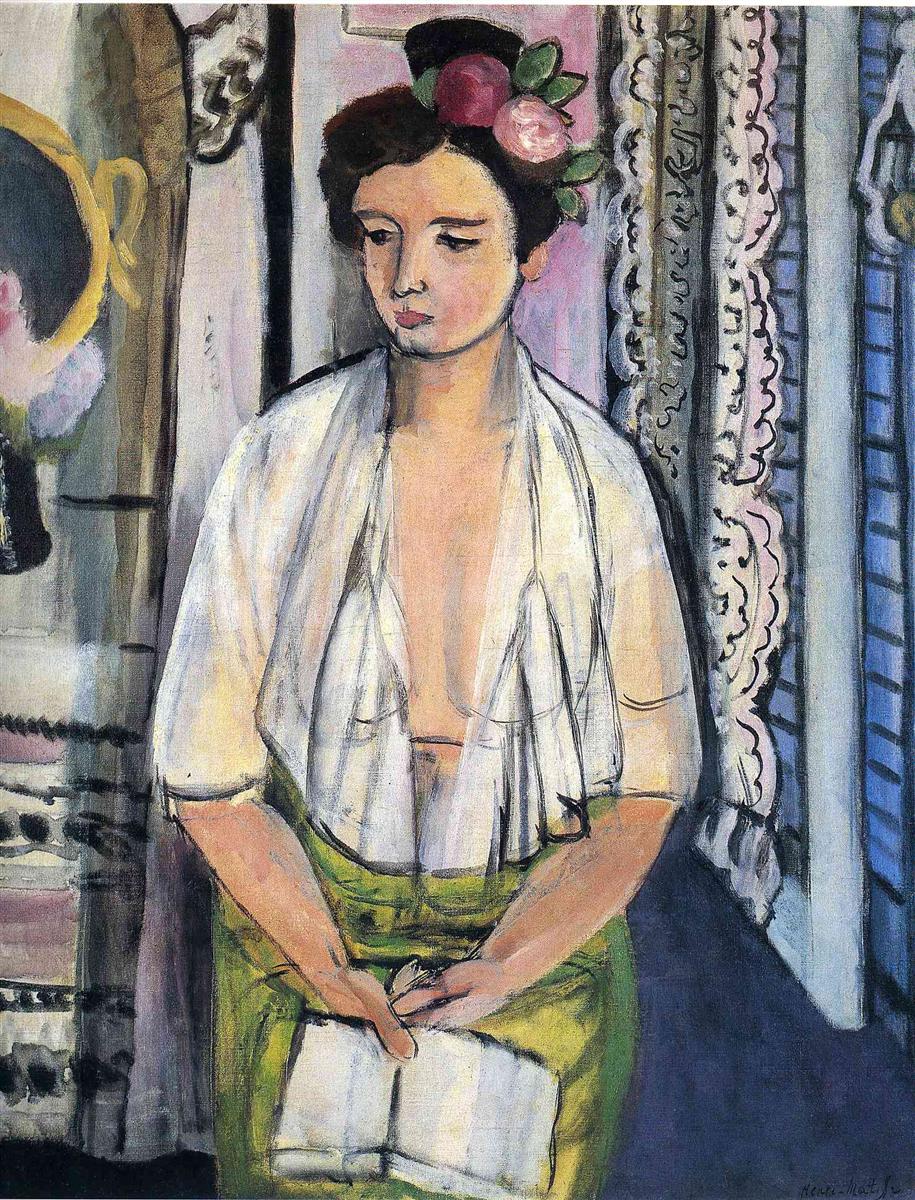

“Reader on a Black Background” places a young woman before a layered wall of patterns, lace, and shutters. Flowers crown her hair; a white blouse opens to a soft V; a citron-green skirt gathers at the waist; and a slim, pale book rests in her lightly clasped hands. To the left, a mirror and drapery form a vertical band; to the right, lace curtains and blue shutters stack into a shallow stage. The title promises darkness, and indeed a vertical current of black anchors the composition, yet the overall feeling is one of breathable light. The face is thoughtful, inward, untheatrical. The painting’s power is the calm of its relations: pale skin against softened blacks, cool shutters against warm textiles, a white book echoing the blouse, the flower crown repeating the small rose warmths of the cheeks and lips.

1918 and the Nice Grammar of Air and Pattern

The year 1918 marks Matisse’s emergence into the Nice period, when he exchanged the carved, high-contrast energies of the mid-1910s for a tuned, domestic lyricism. The Nice grammar is all here. Color is moderated and precise. Black functions as a positive color—structural and musical, not merely an outline. Space remains shallow yet inhabitable, constructed by overlaps and temperature steps rather than by deep perspective. Pattern is disciplined into architecture. And the surface leaves the time of its making visible in economical, confident strokes. This portrait of a reader becomes a manifesto for the new key: a human presence held by air, textiles, and a handful of exact color relations.

Composition as Interlocking Frames

Matisse organizes the composition as a trio of vertical frames. On the left, a dark, nearly black band of mirror and drapery provides the painting’s basso continuo. In the center, the figure stands like a pale pillar edged in soft contour; her blouse opens at the sternum and falls in two translucent panels that rhyme with lace behind her. On the right, the lace curtain and blue shutters stack a gentle column of light. These flanking frames bracket the woman, slowing the eye and drawing attention to her face and hands. The book, a horizontal rectangle, counters the upright rhythm and quietly centers the composition at the level of the clasped fingers. Nothing is superfluous. Each element—mirror, lace, shutter, garment—has a structural job to do.

The Figure’s Pose: Reserve Rather Than Display

The sitter’s posture is self-contained. The head turns slightly to her left, away from the viewer, as if returning to a sentence only she can hear. The shoulders slope modestly; the blouse is open but unprovocative; hands are joined in a loose, habitual fold around the book. Matisse’s ethics of looking—attention without trespass—governs the entire image. There is intimacy but no invasion. The viewer joins the room’s quiet rather than interrupting it.

The Reader as Model of Attention

A book concentrates the portrait’s theme. In Matisse, reading is often a figure for the kind of seeing he asks from a viewer: unhurried, steady, interior. The pale book repeats the blouse’s white, as if the act of reading had become a luminous garment. Because the book is closed or momentarily paused upon, it behaves like a lantern that the hands cradle. The relationship between face and fingers suggests a suspended sentence—the mental and tactile phases of attention held at once.

Palette: Pearly Whites, Citron Greens, and Measured Blues

The palette is maritime and domestic. The blouse and book supply a pearly, warm white that gathers the room’s light. The skirt’s green bends toward citron, refreshed by cooler shadows. Lace is a soft gray-white, more air than cloth. Shutters bring a dense, lavender-blue laid in horizontal strokes, their coolness stabilizing the warmer field of figure and textile. Flesh is a chord of pink ochres with cooler passages at cheek, jaw, and clavicle. The flower crown introduces rose notes of higher saturation—small, decisive sparks that tether the head to warmth and keep the face from drifting into the pale field of blouse and lace.

Black as a Positive, Structural Color

The title’s “black background” does not describe an engulfing void; it names a set of living darks that organize the image. A black vertical in the mirror and drapery at left balances the cool shutters on the right. A fine black line clarifies eyelids, brows, and the edge of the hair, bringing the features into crisp focus without hardening them. A deeper dark anchors the waistline, ensuring the green skirt does not float. These blacks operate as a bass note beneath the paler chords. They steady the painting while allowing whites and pastels to breathe.

Pattern as Architecture, Not Decoration

Pattern is everywhere, yet nothing clamors. Lace is abbreviated to scallops and quick, looping strokes, sufficient to read as transparency and light. The left-side textile introduces a rolling motif, rendered in loose blocks that register as both design and shadow. The shutters’ repetitive horizontals serve as a counter-rhythm to the lace’s vertical fall. Even the blouse is patterned—not by print, but by the logic of folds and pleats. In this room, pattern does the work of architecture. It brackets, articulates, and paces the space.

Light as Climate Instead of Spotlight

Light suffuses the scene as a continuous climate rather than a single beam. The face holds a calm daylight that never glares. The blouse catches light and lets it fall as soft blue-grays in the folds. Lace glows as if made of air. The blue shutters absorb and reflect, deepening the right side while clarifying the edge of the figure. The painter models form by temperature shifts rather than heavy shadow. Warmth lifts where the sternum and cheeks face the room; cool halftones settle in the neck and under the chin; shadows are restrained to narrow seams that nudge volume without drawing attention to themselves.

Edges and Joins: How Forms Share Air

Edges are tailored like seams in a well-made garment. Along the shoulder line, flesh meets lace with a breathed edge that reads as translucence. Along the neckline, a firmer dark, thinly drawn, declares the opening of the blouse without harsh outline. Where hand meets skirt, a shaded join grounds the fingers, reminding us that the book carries weight. The flower crown meets hair with small, scalloped touches that keep the blossoms lively but not sugary. Each join secures the figure in shared air so that the room remains continuous rather than collaged.

Brushwork: The Visible Tempo of Making

The painting keeps its making visible. Flesh is built with medium strokes that turn with bone and muscle. The blouse’s whites are laid in with broader passes that alternate between warm and cool, producing a milky translucence. Lace is a series of loops and taps; the eye can rehearse the painter’s wrist turning along each scallop. Shutters are pulled in horizontal drags that leave narrow ridges—brush-ripples that read as slats. The surface is varied and articulate, but nowhere fussed. This open facture contributes to the picture’s calm; finish is found in relation, not in polish.

A Room of Thresholds

Like so many Nice-period interiors, the painting is built around thresholds: mirror, window, curtain, and shutter. Each is a device for admitting air without relinquishing the room’s privacy. The mirror’s golden rim and smudge of reflected color hint at things unseen beyond the left edge. The shutters promise the sea, though only their cooled light enters the scene. Curtains separate without sealing. The reader stands among these thresholds as a human equivalent: a mind moving between inner sentence and outer day.

The Flower Crown: A Chromatic Keystone

The blossoms in the hair are not merely pretty. They consolidate the head’s authority, gathering the warmest reds in the painting into a compact, textured cluster. Their rounded shapes echo the circular mirror on the left and the loops of lace, binding the composition. And they serve as a chromatic hinge: their pinks echo the lips and cheeks; their greens nod to the skirt; their darker centers dialog with the black band at the figure’s hair. Without the crown, the head might dissolve into the pale neighborhood of blouse and lace; with it, the head sits securely in the room’s climate.

The Hands and the Book: A Quiet Center of Gravity

The hands form a small architecture of their own, nested just above the waist and cradling the book’s edge. Their pinks are cooler and more muted than the cheeks, a difference that reads as distance from the light and as restraint of emotion. Fingers are simplified but proportionally convincing; knuckles are stated with single touches of gray. The book’s pale rectangle repeats the blouse’s value and temperature, fusing the act of reading to the body. This small constellation—the clasped hands, the book, the waistband—composes the portrait’s still center.

Space Kept Close to the Plane

Depth remains near the surface. Overlap and value, not vanishing perspective, produce space. The figure stands before lace, which drops before shutters; mirror and textile on the left move up to meet the figure’s shoulder; a narrow wedge of floor pulls us gently inward at the bottom right. This shallow depth allows the painting to read as a designed surface at a glance while remaining a place one could inhabit. The modernity of the image comes from that balance: it is both room and arrangement.

Dialogues with Tradition without Quotation

The work converses with portrait traditions but refuses to imitate. The open blouse and floral crown faintly recall Spanish and Mediterranean types, yet nothing here is exoticized. The mirror nods to the long history of selfhood staged beside reflections, but Matisse denies any narrative cleverness; the reflection is merely a warm band of color. Decorative abundance hints at the odalisque interiors to come, but the discipline remains classical: geometry first, relations first, human presence held in proportion to the room.

Relations to Sister Works of 1918

Set alongside “Marguerite Wearing a Hat,” “Mlle Matisse in a Scotch Plaid Coat,” or “Woman in White in Front of a Mirror,” this painting clarifies the period’s vocabulary. The balcony stripe of sea recurs here as cooled shutters. Pattern remains structural rather than flamboyant. Black lines articulate rather than imprison. And the sitter’s privacy is preserved by an averted eye and absorbed expression. Compared with the balcony portraits, “Reader on a Black Background” looks inward, trading maritime horizon for the mental horizon of a book.

Guided Close Looking: A Slow Circuit

Begin at the flower crown and let its rose pulses tie head to heartbeat; move down the left cheek where a small cool shadow triangulates with the lips and chin; cross the blouse’s V, watching the whites alternate in warm and cool notes; pause at the clasped hands and feel the slight pressure where fingers meet; read across the book’s pale pages into the green skirt; ascend through the right arm into the lace, following scallops that thicken and thin; slide into the shutter’s lavender-blue and then back along the dark left margin of mirror and drapery to the face. With each circuit, the picture shifts from inventory to cadence.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

The canvas retains small revisions that animate the surface. A restated edge along the jaw clarifies the tilt of the head. A narrow dark corrected at the blouse’s hem deepens the waist. A reclaimed seam brightens the gap between lace and shutter. Matisse leaves these decisions visible. He stops when the relations feel inevitable, not when the paint is cosmetically uniform. The viewer senses that inevitability as calm.

Lessons Embedded in the Painting

Several practical lessons are encoded here. Use black as a color to stabilize light palettes. Model flesh by temperature, not by heavy shadow. Let pattern shoulder structural tasks rather than compete for attention. Keep depth close to the plane so the portrait remains legible at a glance and intimate at length. Design edges that seat forms in shared air. Decide with the brush and let those decisions remain on the surface. Above all, make attention itself the subject: paint someone reading if you want to teach the viewer to look.

Why the Portrait Still Feels Contemporary

A century later, the image looks fresh because it trusts essentials. Big shapes and tuned hues read instantly, while visible process and softened edges keep the painting human. The sitter’s reserve aligns with modern ideas of privacy; her concentration matches our desire for quiet amidst saturation. The room’s decorative intelligence feels designed rather than crowded. It is a portrait one could live with, because it steadies rather than exhausts.

Conclusion: Presence Made from Light, Pattern, and Poise

“Reader on a Black Background” distills a person and a room into a handful of relations: pale blouse and book as a single lantern of attention, green skirt as a grounding field, flower crown as chromatic keystone, lace and shutter as alternating breaths of air, and a bass of blacks that holds the whole in tune. Nothing shouts; everything participates. Matisse gives us not a story but a condition—concentration made visible, privacy respected, daylight domesticated into calm. It is the Nice period in miniature: a poetics of air, pattern, and humane reserve.