Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

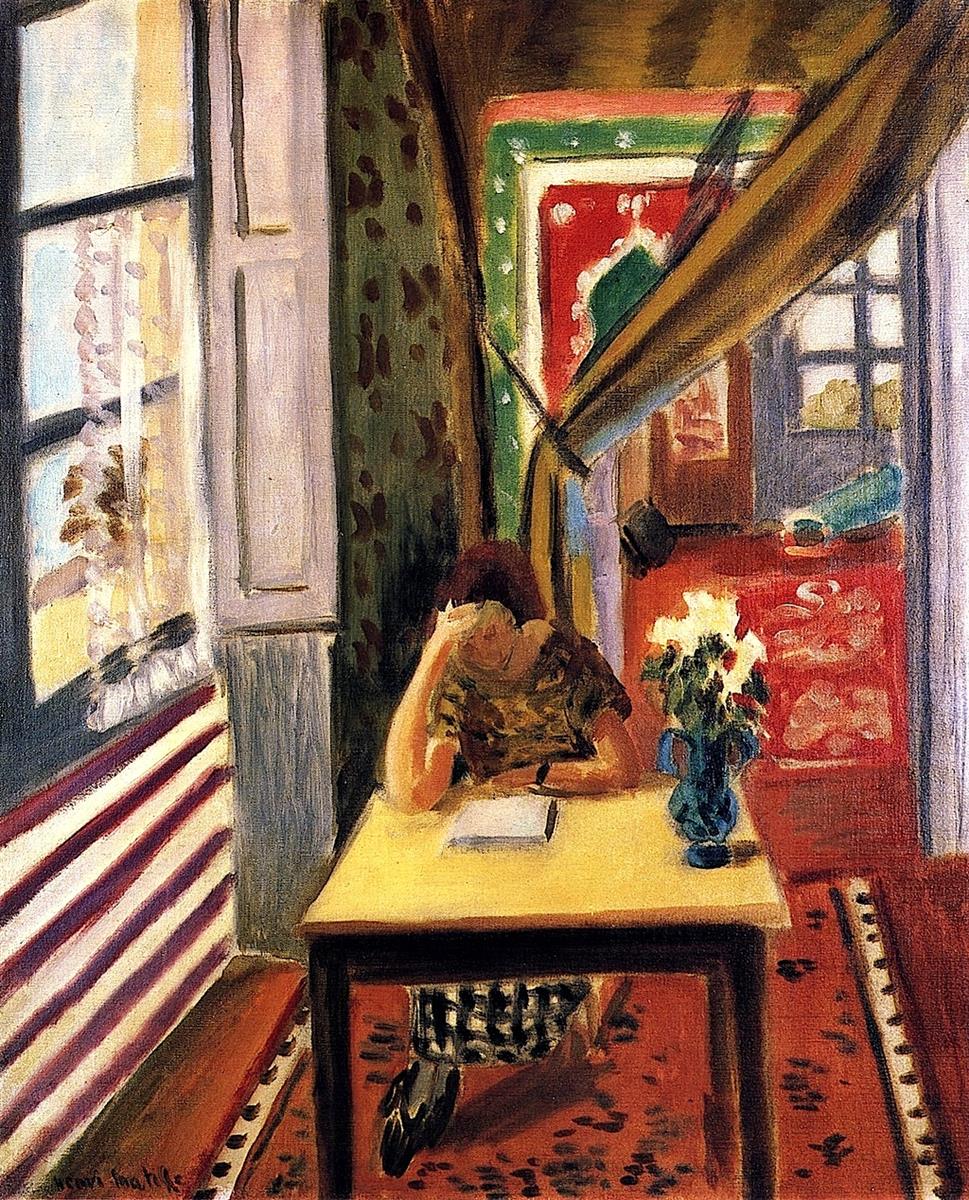

Henri Matisse’s “Reader Leaning Her Elbow on the Table” (1923) captures a quiet act—reading—in a room that seems to hum with color and pattern. Set during his Nice period, when interiors, textiles, and gentle sunlight became his principal stage, this painting transforms domestic space into a theatre of vision. A woman bends toward a page, head propped by her hand, while a square table glows like a pale altar beneath a canopy of angled curtains, carpets, and doorways. The seeming modesty of the subject belies a complex orchestration of light, structure, and chromatic music. In this canvas, Matisse shows how attention—both the reader’s and the painter’s—turns the ordinary into a scene of radiant concentration.

Historical Context

By 1923, Matisse had been working in Nice for several years. The Mediterranean light, the availability of models, and the intimate scale of rented rooms gave him a laboratory to refine a new pictorial language after the shocks of Fauvism. He shifted emphasis from blazing contrast to poised harmony, from agitation to equilibrium. Interiors—often with a window, a patterned curtain, and a figure engaged in simple tasks—became the ideal setting for his aims. “Reader Leaning Her Elbow on the Table” belongs to this world of quiet dramas. It aligns with other works in which women sew, daydream, write, or read, each activity chosen because it harmonizes with the painter’s own act of sustained looking.

Composition and the Architecture of the Room

The composition is a masterclass in how to organize a crowded interior without losing clarity. The table sits near the center, tilted slightly so its top reads like a luminous plane. The reader occupies the near edge, her torso compressed into a triangle formed by the line of her forearm and the downward tilt of her head. To the left, a tall window with a striped cushion bench introduces a vertical shaft of pale light; to the right, a corridor or second room opens onto layers of patterned carpets and a checkered window. A heavy drape diagonally bisects the upper right quadrant, creating a dynamic canopy that both shelters the reader and drives the eye deeper into the painting. Every boundary—the window jambs, the table edge, the carpet borders—acts like scaffolding to contain the abundance of color.

Space as a Sequence of Rooms

Rather than a single box, the picture presents space as a procession. Closest to us: the table, the reader, the vase of flowers. Midground: the green wall and the pulled curtain. Deepest: a red-carpeted room whose walls carry white foliate motifs and whose doorway is framed by a mint-green border. The floor functions like a river of patterned textile flowing from front to back. Because perspective is gently skewed—the tabletop steep, the corridor compact—depth reads not as illusionistic recession but as layered tapestries. The viewer travels through color thresholds: warm red to cool green to glowing cream, then back to red again.

Light and Color as Atmosphere

Light in this painting has the softness of filtered afternoon sun. It enters from the left window, washing the table with a buttery glow and paling the curtain to a warm ocher where it catches the light. Matisse’s palette is anchored in reds and oranges—carpet, distant walls, and soft reflections—balanced by sage greens, violet shadows, and the blue glass of the vase. The reader’s face and forearm are modeled in gentle creams and soft grays, never pushing toward harsh contrast. The interplay of warm and cool keeps the surface alive: the red corridor breathes against the green wall; the blue vase cools the table’s honey tone; the lilac window panes temper the golden light. Color here is not accessory but structure, a system that shapes depth and mood simultaneously.

Pattern and the Decorative Field

The room is dense with pattern: scalloped carpet borders, floral or foliate wall motifs in the distance, spotted green wallpaper behind the reader, and striped bench fabric under the window. Matisse does not treat these as separate decorations; he uses them to generate rhythm across the canvas. Each pattern establishes a beat. The stripes rise and fall near the left edge, a steady metronome. The dotted green wall murmurs behind the figure like a soft drumroll. The red carpet with scattered dark marks spreads a syncopated base line under the table. The effect is musical—a polyphony where design elements sustain the reader’s solitary melody.

The Figure and Gesture of Concentration

The reader’s pose is one of compressed attention. Her hand props her head, elbow firm on the table, shoulders slightly forward. The face, though generalized, conveys inwardness through two economy moves: the tilt of the head and the shadow falling over the brow. In Nice-period works Matisse often avoids psychological detail, preferring a more universal mood. Here, the lowered gaze and resting cheek make the act of reading palpable without anecdote. She is not an illustration of a story; she is a figure of thought itself—a body arranged by the mind’s weight.

The Table as a Luminous Stage

The square table is a pivotal actor. Its top is a warm, light plane that concentrates the painting’s illumination. It hosts three elements: the reader’s hand and paper, the vase of white blossoms, and the faint reflection of light pooling at the near edge. The table’s legs, darker and more solid, anchor the composition to the carpet. Beneath, a sliver of the reader’s skirt and her shoes confirm the human scale and add a flicker of black that ties to the dark specks in the carpet. The table is both practical furniture and pictorial device: a quiet platform that renders thought visible.

Window, Curtain, and the Drama of Thresholds

No Nice-period interior is complete without the theatre of windows and curtains. At left, the window’s panes and shutters create a cool geometry that counters the organic patterns elsewhere. The translucent lace filters sunlight into chalky whites and mauves. At right, the ocher curtain falls diagonally, its sweep transforming the rectangle into a tent-like enclosure for the reader. This curtain is pivotal structurally; it creates a wedge that points into the distant doorway, guiding the eye deeper. It also suggests movement—someone has just drawn it back—while simultaneously freezing the moment into poised stillness. Matisse uses thresholds to frame attention: light crossing glass, textile crossing air, the open doorway crossing rooms.

Perspective, Skew, and the Sense of Nearness

Matisse’s perspective is deliberately elastic. The table leans; doorframes compress; the bench elongates. These distortions are not mistakes; they keep the viewer physically close to the scene. A perfectly rational space would push us back; this slanted geometry lets us hover just over the table’s edge, breathing the same air as the reader. It also allows color to do the work of depth. The receding corridor is constructed not by vanishing points but by transitions in color intensity—from saturated scarlet to paler, cooler tones toward the far window. The skew becomes a tool to keep the painting open, alive, and tactile.

Brushwork, Surface, and the Record of Making

The brushwork is varied and purposeful. In the carpet and curtain, strokes are broad and loaded, leaving ridges that catch the light. Along the left window, paint thins so the weave of the canvas flickers through, heightening the sensation of air and glare. The face and hand are scumbled gently, preserving softness. The flowers are flicked in with quick, creamy touches that avoid fuss. Matisse’s restraint is key: he stops when a passage says enough. The surface retains the tempo of its making—measured, economical, assured.

Rhythm and the Time of Reading

Everything in the room participates in the tempo of reading. The stripes along the bench suggest a page’s lines; the spotted wall behind hums like words murmured in the mind; the carpet’s specks echo the dance of letters. The reader’s pause—hand to temple—mirrors the curtain’s pause where it is looped and gathered. Even the vase’s whites seem to glow with the quiet intensity of concentration. The painting is not only a picture of a reader; it is a map of reading’s rhythm translated into architecture, color, and line.

Emotion Without Drama

Matisse’s painting does not seek theatrical emotion. Its power derives from poise. The reader’s inwardness, the room’s gentle order, and the moderated palette create a feeling of domestic refuge. The painting acknowledges the world’s noise—the angled curtain, the layered rooms, the bright outside light—yet gathers it into a sanctuary of attention. The emotion is trust: trust in rooms to hold us, in color to soothe and stimulate, in a page to anchor thought. This quiet confidence is one of the Nice period’s most lasting contributions to modern painting.

Relations to Other Nice Interiors

Compared with contemporaneous odalisques, “Reader Leaning Her Elbow on the Table” is modest and clothed, eschewing theatrical costume for a simple dress and shoes. Yet the structural logic is consistent: a figure stabilized by patterned décor, a warm field balanced by cooler intervals, a shallow space activating the picture plane. Where the odalisque paintings often deploy pinks and saturated reds as sensual climate, the reader’s room prefers a warmer orange-red carpet and a thread of cooling greens. The emphasis shifts from pose to posture, from display to absorption. In this way, the painting broadens the Nice vocabulary to include the intellectual sensuality of reading.

The Bouquet and the Reading Mind

The blue glass vase with white blossoms is more than a still-life insert. It is an analogue for the reader’s mind at work. The blooms flare upward like sparks, their whites taking on surrounding hues—warm at the edges, cool at the centers—just as thoughts absorb the tones of their environment. The blue vessel cools the table’s glow, acting as a counterpoint to the warm carpet. Placed slightly to the right, the bouquet balances the reader’s weight on the left edge of the table. Object and figure together conduct the room’s energy into a calm chord.

Material Culture and the Modern Interior

Matisse’s interiors are both specific and archetypal. The striped bench cushion, the patterned carpets, the brocaded drapery, the glass vase—these speak to a European, Mediterranean-inflected domestic culture in the 1920s. Yet they are abstracted into signs more than described as objects. Their identities matter less than their energies. The modern interior in this painting is a place where everyday items are enjoyed for their colors and shapes, not their prestige. Matisse’s democratic eye grants the same dignity to a curtain fold as to a human cheek, provided both serve the painting’s harmony.

Looking Today: A Guide for Slow Seeing

To truly see the painting, begin at the table’s closest edge. Let your gaze lift to the reader’s hand and travel across the page’s pale rectangle. Move to the bouquet and feel the cooling blue. Follow the curtain’s diagonal into the doorway and down the red corridor; note how the green frame arrests your motion and returns you to the table. Visit the left window and trace the lavender panes, then drop to the striped bench and let those lines steer you back toward the figure. This circular path—table, reader, bouquet, corridor, window, bench—matches the painting’s own rhythm. Each loop reveals new connections: the echo between the page and the windowpane, the kinship between carpet dots and inked words, the way the curtain’s ocher ties to the table’s warmth.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

“Reader Leaning Her Elbow on the Table” contributes to a lineage in which everyday attention becomes the subject of art. Later painters who explored interiors—Bonnard with his bathing rooms and breakfast tables, Fairfield Porter with his domestic scenes, Richard Diebenkorn with his Ocean Park windows—owe a debt to Matisse’s balance of pattern and calm. Designers and photographers, too, have borrowed his method of letting textiles and light create spatial rhythm. In a contemporary world of distraction, the painting’s focus on a single page feels quietly radical. It models a way of living with color and objects that nourishes rather than overwhelms.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse turns a reader at a table into a symphony of thresholds—table to page, window to air, curtain to corridor—held together by warm carpets and cooling greens. The painting’s calm is not passive; it is the equilibrium achieved when every element, from a stripe to a shadow, takes its rightful place. In “Reader Leaning Her Elbow on the Table,” the act of reading becomes a visual ethic: attention is beautiful, concentration is luminous, and rooms can be composed like music. The canvas offers not an escape from life but a refined image of how life feels when color, light, and thought are in tune.