Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

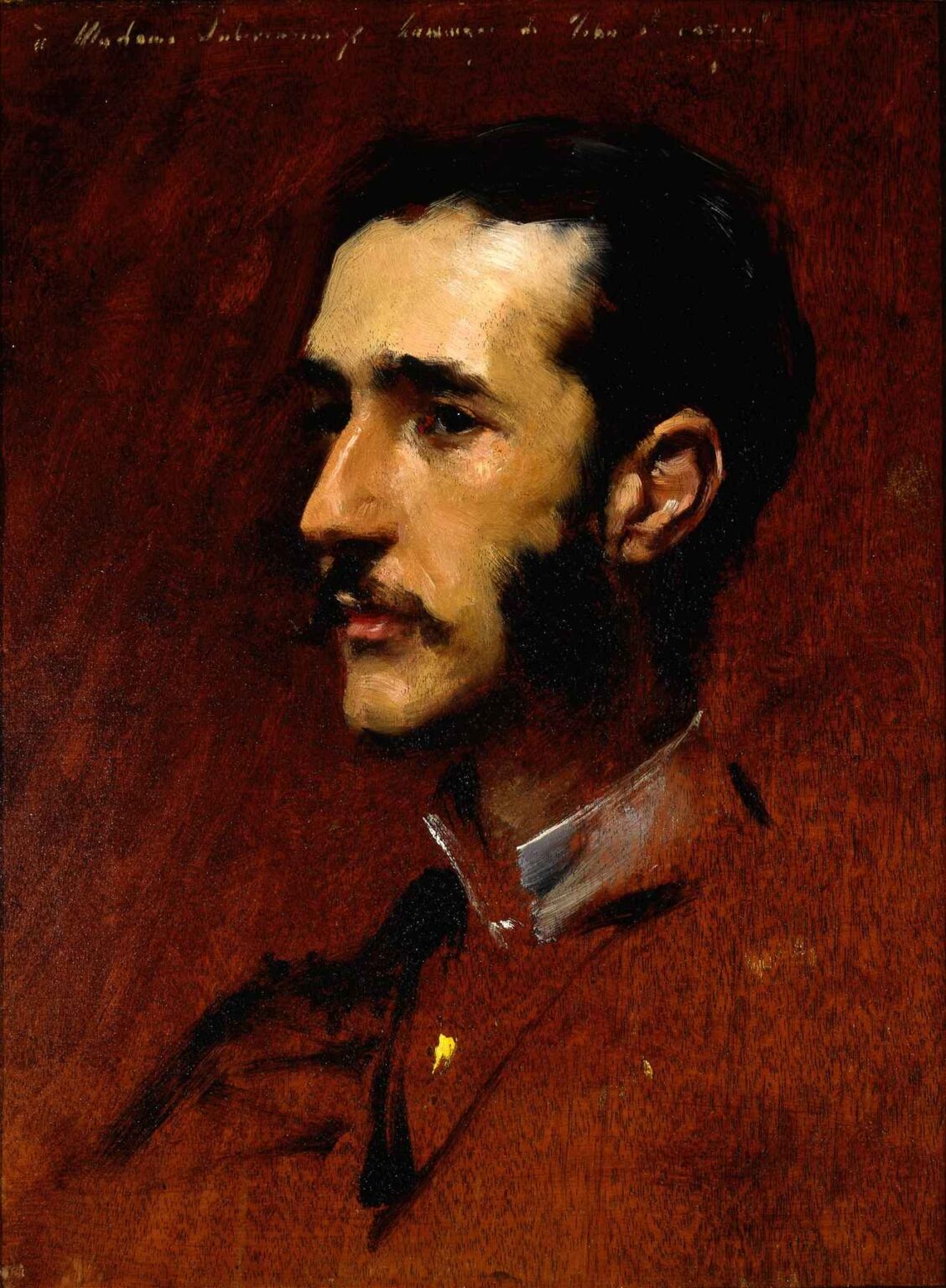

John Singer Sargent’s Ramon Subercaseaux (1880) is a masterful example of plein‐air portraiture that blends refined draftsmanship with a bold economy of brushwork. Painted when Sargent was just 23 years old, this oil study captures the Chilean diplomat and painter Ramón Subercaseaux Vicuña in a moment of composed introspection. Far from a stiff academic likeness, Sargent’s portrait pulses with vitality: warm underpainting shows through the translucent layers, and brisk strokes articulate the sitter’s features, attire, and the resonant background. In this analysis, we will explore how Sargent’s compositional choices, handling of light and color, brushwork, and psychological insight combine to create a portrait that remains both intimate and grand.

Historical and Biographical Context

Ramon Subercaseaux (1854–1937) was a member of one of Chile’s most prominent families, known for banking, politics, and the arts. Educated in Europe, he cultivated friendships with leading cultural figures of his time. In 1880, Subercaseaux commissioned the young Sargent—then building his reputation in Paris—to capture his likeness. This period coincided with Sargent’s studies under the influential portraitist Carolus-Duran, whose emphasis on alla prima painting and the careful observation of light profoundly shaped Sargent’s approach. Ramon Subercaseaux thus emerges at a pivotal moment: Sargent’s academic training had merged with his desire for painterly immediacy, and his transatlantic clientele included figures such as Subercaseaux who appreciated both technical skill and artistic daring.

Composition and Framing

The composition of Ramon Subercaseaux is deceptively simple yet carefully orchestrated. Sargent frames the sitter in a loosely cropped profile, filling much of the vertical plane with the head and shoulders. The subject’s head is positioned slightly above center, drawing the viewer’s eye to his contemplative gaze. The stainless red‐brown background tightly hugs the sitter, eliminating spatial distractions and emphasizing the interplay of figure and ground. The scant visible lapel and high collar provide just enough cue to the sitter’s attire, while the interruption of brushwork below the collar suggests the beginning of a jacket without detailing it fully. This restrained framing underscores the portrait’s intent: direct engagement with the sitter’s countenance and spirit rather than elaborate setting.

Use of Light and Shadow

Sargent’s treatment of light in this study is particularly noteworthy. A soft, diffuse illumination falls across Subercaseaux’s face from the viewer’s left, creating delicate modeling of the cheekbones, brow, and nose. The left side of the face is bathed in gentle highlights—painted with thin, radiant glazes—while the right side recedes into cooler, subdued shadows. This chiaroscuro approach sculpts the sitter’s features convincingly, yet the transitions remain smooth and natural. The ear, rendered with a few deft strokes, catches a sliver of light that anchors the profile. Subtler still is how Sargent allows the warm underpainting to show through in the shadows, imparting a vibrancy to the skin tones and preventing the portrait from feeling lifeless or overworked.

Color Palette and Tonal Harmony

Sargent’s palette in Ramon Subercaseaux revolves around warm siennas, burnt umbers, and ochres contrasted with muted flesh tones and touches of cooler grays. The background’s reddish‐brown hue complements the sitter’s complexion and dark hair, creating visual unity. Subercaseaux’s jacket—indicated by a smudge of deeper red—echoes the background, binding figure and ground. Sargent avoids jarring contrasts, opting instead for a harmonious tonal range in which every hue supports the portrait’s subtle emotional tenor. Even the whites of the sitter’s eyes and teeth are integrated through gentle glazing rather than stark highlights, reinforcing the overall sense of cohesion.

Brushwork: Precision Meets Spontaneity

A defining feature of Sargent’s early work is the dynamic balance between refined detail and bold suggestion—and Ramon Subercaseaux exemplifies this. The sitter’s facial features receive careful attention: the arch of the brow, the slope of the nose, and the shape of the lips are all articulated with precise, controlled brushstrokes. Yet these carefully rendered areas sit within a broader context of looser handling. The hair, for instance, is painted with sweeping, gestural strokes that convey volume and texture without delineating every strand. The background and clothing are indicated with rapid, confident marks that suggest form through shifting tonal values rather than explicit contour. This interplay of tight and loose brushwork energizes the portrait, lending it immediacy and vitality.

Psychological Depth and Character

Beyond technical prowess, Sargent’s portrait succeeds in conveying the sitter’s psychological presence. Subercaseaux’s eyes, directed slightly off‐canvas, carry a thoughtful intensity reinforced by the slight furrow of his brow. His lips, gently parted, hint at a reflective temperament. Sargent captures these nuances without overwrought dramatization; instead, subtle variations in color and value around the eyes and mouth articulate a spirit of quiet contemplation. The sitter’s upward‐tilted head and the elongation of his neck lend an air of poise, suggesting personal dignity and intellectual engagement. In a single glance, viewers sense both Subercaseaux’s social standing and his inner life.

Attire and Textile Suggestion

Although the painting focuses on the sitter’s face, sartorial cues play a pivotal role. The high shirt collar—rendered in a few strokes of white and gray—frames the face and anchors the composition. A hint of a jacket lapel in darker, cooler tones signals formal attire appropriate to a diplomat. Sargent eschews exhaustive detail in the clothing, instead suggesting fabric through swift marks that convey material weight and form. This approach aligns with the portrait’s overall economy: when you paint only what you need, the viewer’s imagination completes the rest, deepening engagement with the work.

Background as Character

Rather than a blank slate, the background in Ramon Subercaseaux functions almost as a character itself. Sargent layers brushstrokes of warm underpainting with cooler overlays, creating a subtly textured field that pulses with energy. The background’s mottled surface contrasts with the sitter’s smooth modeling, lending depth without distracting from the face. The warmth of the backdrop also bathes the sitter in an enveloping glow, reinforcing the portrait’s intimate scale. Through this deft handling, Sargent demonstrates how background itself can support emotional mood and emphasize the sitter’s presence.

Influence of Spanish Masters

Sargent’s portrait draws inspiration from Spanish masters such as Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya, whose spare yet penetrating studies of character Sargent admired. Like the Velázquez portraits at the Prado, Ramon Subercaseaux relies on rich tonal harmonies and subtle chiaroscuro to convey psychological depth. The spare composition, with minimal figural context, echoes the directness of Velázquez’s early court portraits. Sargent’s own review of these works during his Paris years undoubtedly informed his approach here: the idea that less can indeed be more, and that a few masterful strokes can reveal a soul.

Sargent’s Transition to Modernity

Painted at the dawn of Impressionism’s influence in Paris, Ramon Subercaseaux reveals Sargent’s ability to synthesize academic training with avant‐garde sensibilities. He retains the realism and anatomical accuracy valued by the Salon, while embracing the Impressionist emphasis on light and color dynamics. The rapid, sketch‐like passages and evidences of wet‐into‐wet application foreshadow the freer handling Sargent would showcase in later plein‐air works. This portrait thus marks a crucial moment in his artistic development: the confident assertion that portraiture could evolve without forsaking fidelity to character.

Comparative Analysis with Other Early Works

When compared with Sargent’s Portrait of Carolus-Duran (1879) or Portrait of Madame Gautreau (1883), Ramon Subercaseaux feels both related and distinct. Carolus-Duran’s likeness is more formal, with precise edge work and a stiffer pose. Madame Gautreau’s scandalous pose and bold costume reveal Sargent’s willingness to court controversy. In contrast, Subercaseaux sits for an intimate, understated study—an exercise in soulful restraint. The three portraits together illustrate Sargent’s range: from formal academic homage to daring society statement to introspective study. This diversity cemented his reputation as a portraitist who could satisfy any patron’s desires while maintaining artistic integrity.

Legacy and Influence on Portraiture

Though less famous than some of Sargent’s grander canvases, Ramon Subercaseaux remains a touchstone for portrait artists interested in merging realism with painterly freedom. Its enduring influence lies in demonstrating how strategic omissions and confident brushwork can reveal more about a sitter than exhaustive detail. Contemporary portrait painters often cite Sargent’s early studies, like this one, as models for conveying psychological presence with economy and grace. The portrait’s balance of restraint and vitality continues to inspire dialogues about how modern artists can capture the essence of their subjects.

Conclusion

John Singer Sargent’s Ramon Subercaseaux (1880) exemplifies the artist’s early genius: an ability to distill character through masterful composition, nuanced color, and varied brushwork. In just a few deft strokes, Sargent conveys the sitter’s intellect, social standing, and inner life, all against the backdrop of a harmoniously textured ground. The portrait stands as a testament to the evolving language of late‐19th‐century art—where academic rigor and emerging modern sensibilities converged. Over 140 years later, Ramon Subercaseaux continues to captivate viewers, reminding us of the power of painting to transcend time and capture the soul.