Image source: artvee.com

Historical and Cultural Context

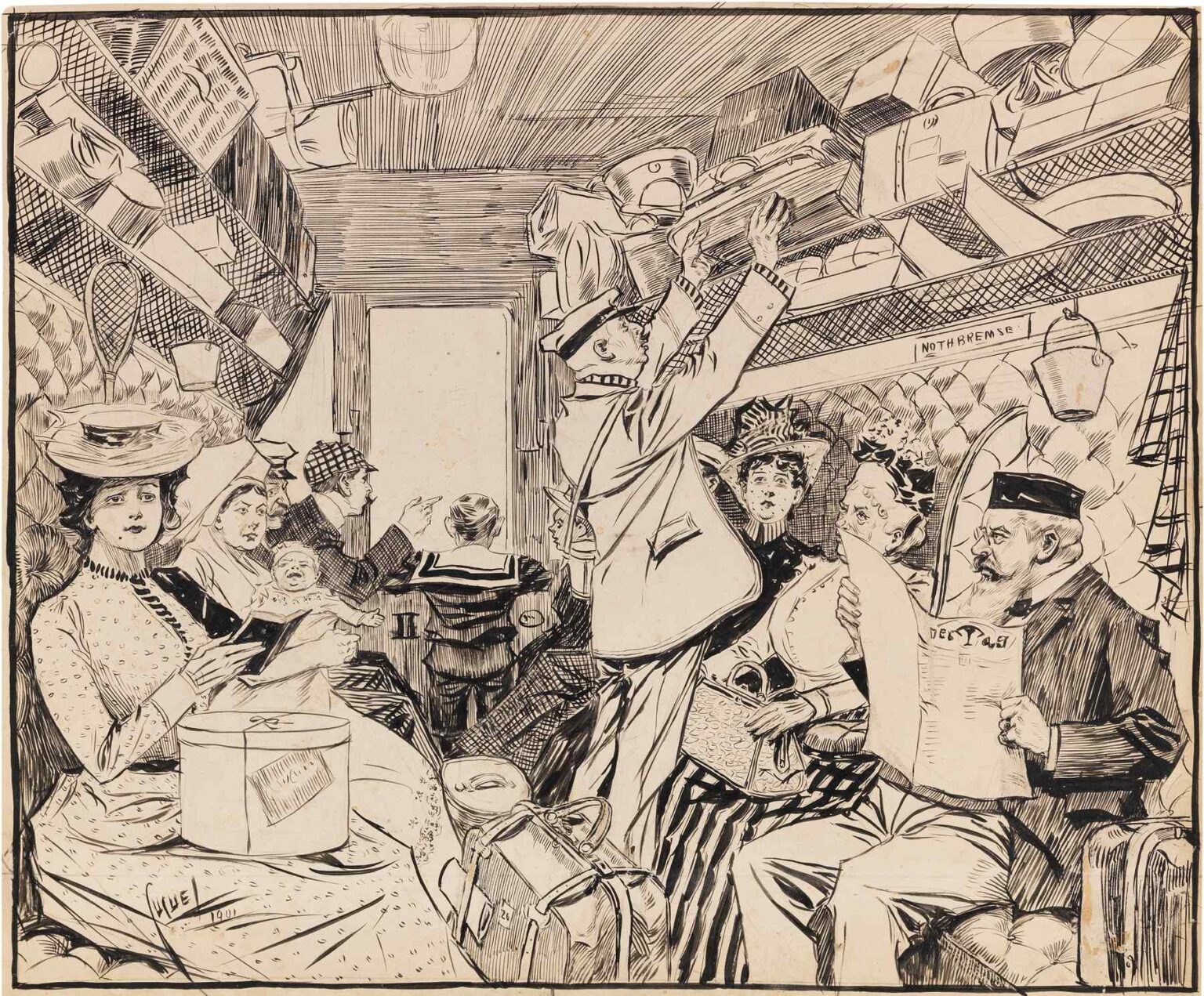

At the turn of the twentieth century, railway travel had become a defining feature of modern life, symbolizing mobility, progress, and the democratization of journeying. In 1901, Edward Cucuel captured this zeitgeist in his pen‑and‑ink drawing “Railway Compartment,” a lively tableau of passengers sharing a confined space while en route to destinations both mundane and exotic. Cucuel, an American‐born artist raised in Germany, honed his skills in Stuttgart and later New York before immersing himself in the Munich Secession and Parisian avant‑garde circles. His acute observational powers and deft draftsmanship shine in this work, which commemorates the social microcosm of a compartment car—where class distinctions, generational dynamics, and cultural curiosities unfolded in equal measure.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Cucuel arranges his composition within the strict confines of a rectangular frame that mimics the compartment’s rigid geometry. The walls, ceiling, and benches are delineated by parallel hatching, creating a sense of enclosure. Overhead, luggage racks brim with trunks, hatboxes, a tennis racket, and other personal effects, their dense cross‑hatched lines contrasting with the open hatch of the doorway at center. The vanishing point lies just beyond this threshold, inviting the viewer to imagine the landscape rushing past. Within this tight space, Cucuel balances vertical, horizontal, and diagonal axes: the standing porter’s uplifted arms form a central vertical thrust, while the seated figures and bench backs generate horizontal counterpoints. Diagonal floorboards and the tilt of the baby’s pram draw the eye into the scene’s depth, unifying the compartment’s bustle into a coherent whole.

Character Studies and Social Nuance

“Railway Compartment” functions as an ensemble portrait, presenting a cross‑section of society in transit. On the left, a well‑heeled woman in a dotted bodice and elaborate hat consults a travel guide, poised between curiosity and composure. Beside her, a nursemaid struggles soothingly with an infant, whose tear‑streaked face conveys the rigors of confined travel. A young boy in sailor suit stands before the doorway, his back to us as he peers down the corridor—a gesture of childhood wonder at the iron road’s vast network. To the right, an elderly gentleman in a kepi reads his newspaper, seemingly impervious to surrounding commotion, while the woman beside him glances anxiously overhead, anticipating the porter’s next burden. Each figure’s attire, gesture, and facial expression speak to distinct roles and attitudes: the adventurer, the caregiver, the observer, the escapist, and the seasoned commuter.

Gesture, Movement, and Humor

Central to the drawing’s vitality is the porter—a uniformed railway employee—in mid‑action, stretching to secure a heavy trunk in the overhead rack. His upwardreaching arms and arched back create both tension and comic relief, as fellow passengers watch with varying degrees of interest and apprehension. The baby’s wide‑eyed stare and the matron’s startled expression mirror his straining effort, while the well‑dressed woman maintains her dignity, reading on as if oblivious to the turmoil. Cucuel’s inclusion of everyday humor—bent bodies, shifting luggage, and animated reactions—imbues the scene with warmth and authenticity, reminding viewers that travel’s romance often resides in its small absurdities.

Line Work and Draftsmanship

Executed in black ink on cream‑toned paper, Cucuel’s drawing exemplifies mastery of linear technique. He employs an array of hatching styles—vertical, horizontal, diagonal, and cross‑hatching—to articulate form, texture, and light. The compartment’s quilted wall panels appear plush under dense, parallel lines, while the luggage racks are defined by crisscross patterns that suggest metal mesh. Figures emerge from carefully controlled contours, their clothing detailed through delicate stippling and short linear accents. The precision of his pen strokes captures both the structural integrity of the railway car and the ephemeral gestures of its occupants, demonstrating a harmonious blend of accuracy and expressiveness.

Perspective and Viewer Engagement

Cucuel adopts a slightly elevated viewpoint, as though the spectator stands just inside the open compartment door. This angle enhances the sense of immersion, placing us among the travelers rather than at a remove. The open doorway at center serves as both literal and metaphorical portal—linking interior and exterior, private and public, departure and arrival. By including this aperture, Cucuel invites viewers to step onto the platform or wander down the corridor, bridging the gap between observation and participation. The resulting spatial tension keeps the eye mobile, oscillating between the dynamic interior life and the promise of onward movement.

Textural Contrasts and Material Culture

Through varied line densities, Cucuel differentiates textures—soft upholstery, polished wood, crumpled hats, and glossy paper. The baby’s pram, with its woven basket and curved hood, contrasts with the rigid geometry of the portmanteaus, reflecting the era’s intersection of craftsmanship and industrial production. The tennis racquet tucked above a steamer trunk hints at leisure travel and the Victorian penchant for sports, while the newspaper headline reading “Der Tag” situates the scene in a German‐speaking context. These material details enrich the narrative, situating each passenger within a broader matrix of travel accessories, social customs, and regional specificity.

Narrative Layers and Interpretive Depth

While on the surface “Railway Compartment” appears a humorous snapshot of intransi,t it also bears deeper thematic resonances. The compartment becomes a microcosm of modern life—fragmented yet interconnected, private yet exposed. Each passenger, isolated in their concerns, nonetheless shares a collective experience of confinement and motion. The drawing invites reflection on the paradox of late nineteenth-century progress: railways offered unprecedented freedom of movement yet imposed new constraints of timetable, space, and social proximity. Through this lens, Cucuel’s work transcends pure genre illustration, offering astute commentary on the human condition in an age of accelerating mobility.

Technical Execution and Ink Mastery

Cucuel’s choice of pen and ink allowed for crisp, archival clarity well suited to the era’s illustrative demands. The unvarnished paper tone provides a mid‑value backdrop, making both pure whites (uninked areas) and dense blacks (saturated hatches) resonate vividly. His modulation of line weight—thin for distant or decorative elements, thick for foreground contours and figure outlines—reinforces the spatial hierarchy. The absence of wash or shading ensures that line becomes the sole vehicle for modeling, demanding exacting control and confident economy of stroke. The result is a precise, energetic image that conveys both structural integrity and animated gesture.

Comparative Context and Influences

“Railway Compartment” aligns Cucuel with contemporaries who chronicled modern life and urban experience—such as Jean Béraud in Paris and Henri de Toulouse‑Lautrec in Montmartre. Yet his work retains a distinctly German‐American sensibility, blending satirical observation with restrained draftsmanship inherited from Jugendstil illustrators. Unlike the more caricatural approach of some poster artists, Cucuel’s characters, though humorous, remain grounded in realistic proportions and credible expressions. His compartment scene stands as an early example of travel illustration, prefiguring later developments in graphic reportage and the embrace of everyday subjects by avant‑garde artists.

Provenance and Exhibition History

First exhibited in Munich in 1901, “Railway Compartment” garnered favorable attention in the city’s vibrant illustration circles. It appeared in print journals and inspired reproductions in travel magazines, helping to establish Cucuel’s reputation as a keen observer of contemporary life. In subsequent decades, the drawing entered private collections in Germany and the United States, resurfacing in retrospectives of early twentieth‐century illustration. Today, it is recognized as a significant document of pre‑automobile mobility and remains a highlight in exhibitions exploring the intersection of art, travel, and social history.

Contemporary Relevance and Legacy

In an era defined by high‑speed trains and digital connectivity, “Railway Compartment” retains its charm as a reflection on communal travel and human eccentricity. Modern viewers, accustomed to open‐plan seating and Wi‑Fi, find resonance in the drawing’s themes of cramped quarters, luggage overflow, and the unexpected encounters that define shared journeys. Cucuel’s work presages contemporary graphic reportage, where artists document lived experiences in transit—whether by train, bus, or airplane—highlighting the continuing fascination with the social microcosm of travel.

Conclusion

Edward Cucuel’s “Railway Compartment” stands as a masterful convergence of technical skill, social commentary, and narrative humor. Through precise line work, dynamic composition, and astute character studies, he transforms a transient moment into a vivid exploration of modern mobility. The drawing’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to evoke both the novelty of train travel in 1901 and the timeless quirks of human nature when confined together. As a cultural artifact and an artistic achievement, “Railway Compartment” invites viewers to appreciate the artistry of illustration and to reflect on the shared adventures that continue to define our journeys.