Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

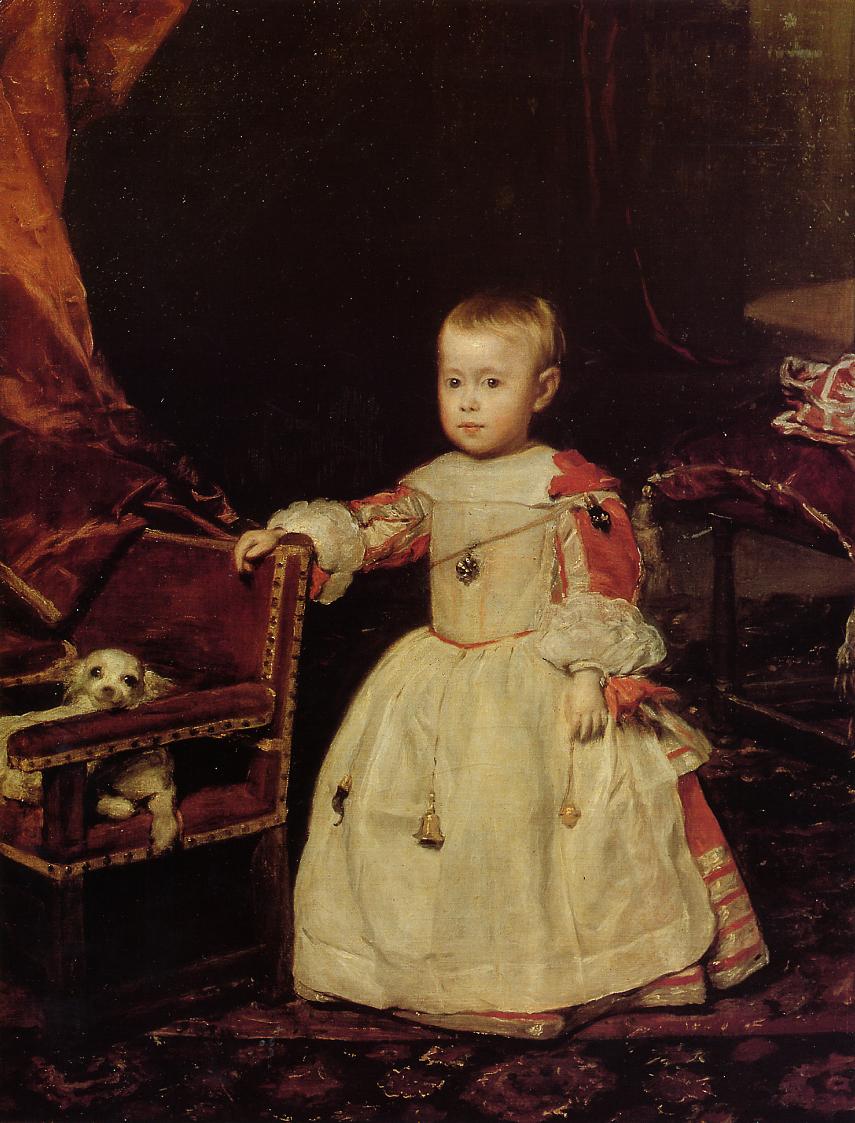

Diego Velázquez’s “Prince Philip Prosper, Son of Philip IV” (1659) is a portrait that marries ceremony with vulnerability. The toddler prince stands in a dim, resonant interior, wrapped in the ritual fabrics of Spain’s Habsburg court. A small dog peeks from a child-sized chair at his side, a thread of domestic warmth in an image burdened by dynastic expectation. The dress bristles with talismans and amulets meant to guard a frail life, and the painter’s late, economical brush converts brocade, braid, and lace into living light. Rather than create a symbolic cipher, Velázquez stages a quiet encounter with a little boy who carries a crown-sized future and the fragility of any child. The portrait is tender without sentimentality, regal without theater, and unguardedly human.

A Dynasty’s Hope Painted With Honest Light

When Velázquez painted the prince—known in Spanish as Felipe Próspero—Spain needed heirs and assurances. Court portraits were instruments of continuity, tokening the health and promise of the royal family. The boy had been born in 1657 after years of losses and would live only a few years; anxiety about his survival was woven into daily life at court. Velázquez meets this anxious hope with candor. He makes the child present in his actual proportions, his soft, watchful face, and his tentative posture. The painter does not enlarge the figure with contrived architecture or a monumental prop; he lets the boy’s presence grow from air, light, and attention.

Composition As Chamber Stage

The composition is a shallow stage where shapes of red, cream, and shadow organize the eye. The child stands slightly right of center, facing forward, one hand resting on the chair and the other hanging at his side. The empty space above his head is not wasted darkness; it is breathable atmosphere that elevates him visually without resorting to columns or thrones. A crimson drapery on the left and the reddish carpet underfoot echo the crimson accents in the prince’s sleeves and sash, binding the room to the child. On the right a richly upholstered seat and domestic furnishings recede into dusk. This asymmetrical balance is characteristic of Velázquez’s late design: the painting feels poised and unforced, like the room discovered rather than staged.

The Language Of Color And Tone

Velázquez limits the palette to deep reds, warm creams, ashen grays, and subdued gold. Light falls from high left, inflaming the curtain and the boy’s garments before dissolving into the room’s brownish air. The white apron-dress and cuffs are not simply white; they feed on grays and light ochres that turn to pearl in the highlights. The reds pulse with quiet saturation, never garish, always part of the same climate of light. Because values are tuned to a single key, the painting reads as one breath: the child, the dog, the furniture, and the drapery reside in a unified atmosphere rather than in separate compartments.

Brushwork And The Courage Of Economy

The surface is a compendium of Velázquez’s late shorthand. The carpet’s pattern is laid in quick, broken strokes that cohere at distance into a field of arabesques. The chair’s gilded studs are brief, thick touches that catch real light; their precision is optical, not descriptive. Lace ruffles are flickers of bright impasto rather than counted stitches. The dog’s fur is a few agile whisks over a warm ground, enough to suggest wet nose and eager eyes. The prince’s face receives the most careful transitions—wet-into-wet planes around the eyes and mouth that keep expression alive without hard outline. Nothing is over-explained; everything is sufficient.

Costume, Amulets, And The Poetics Of Care

Court costume could swallow a child, and Velázquez acknowledges its weight while preventing it from becoming armor. The child wears a long, pale over-dress with red accents, a sash with tassels, and small medallions and capsules suspended at the chest and waist. These are not merely ornaments; they are protective amulets and reliquaries, common in Spanish infancy, meant to ward off illness. Their glinting presence brings a tremor of tenderness to the picture, a reminder that beneath the clothing of rank the sitter is a fragile body loved and worried over. Velázquez paints these objects with respect but without fetish—small constellations of gold that punctuate the soft planes of cloth and skin.

A Face That Is Both Child And Prince

Velázquez refuses to turn the boy into a miniature adult. The head is large in proportion to the body, the cheeks round, the gaze steady but unassuming. The eyes hold minute, exact lights that animate the entire likeness. The mouth is relaxed, neither forced into a smile nor tightened into stoic gravity. This honesty feels revolutionary in court portraiture: the child’s authority does not come from theatrical sternness, but from his unadorned presence. He is a person first, a prince second—and this ordering is precisely what makes the portrait credible.

Gesture And The Discipline Of Stillness

The child stands because portraits require standing; his hand rests on the chair because toddlers need anchoring. These necessities become expressive gestures in Velázquez’s hands. The resting hand reads as both support and introduction, as if the boy quietly presented the small dog who shares his stage. The other hand’s relaxed fall, with tiny fingers slightly curled, conveys the bodily facts of a small child in a heavy garment. Court etiquette is visible, but childhood persists: a soft sway in the posture, a head that rises toward the light.

The Dog As Companion And Counterpoint

The toy-sized dog peering from the chair is not an anecdotal afterthought. It provides scale, revealing how small the prince truly is, and it invents a triangle of attention: the boy to the viewer, the dog to the boy, and the viewer back to the dog. The animal’s bright eyes and alert muzzle bring a spark of humor and vitality that intensifies, by contrast, the formality of the setting. With a few strokes Velázquez builds a creature that breathes the same air as the child, a point of warmth in a room of responsibilities.

Furniture, Drapery, And The Room’s Rhythm

The painter builds the setting not from emblematic architecture but from textures: wood with worn gilding, a velvet seat with folded gloss, a curtain that drinks and releases light in long waves. These things are chosen because they are felt. The small chair is scaled to childhood; the drapery’s color binds the room to the garment; the darker recess where furniture melts into shadow keeps our focus where it belongs. Nothing in the arrangement distracts, and yet everything contributes to a rhythm of verticals and diagonals that makes the quiet scene vibrate with life.

The Democracy Of Air

Velázquez is famous for placing sitters—royals, buffoons, dwarfs, saints—in the same breathable darkness. That democratic air is the real setting here. Background space is not a painted wall or a scenic illusion; it is the room’s shared atmosphere, a tonally modulated void from which faces and fabrics seem to precipitate. The effect is to unify the portrait’s many truths—rank, affection, anxiety—under one light. This is why the painting feels immediate: the child stands in the same kind of air that we ourselves inhabit.

Time, Mortality, And The Tender Stoicism Of Late Velázquez

Viewed with historical hindsight, the portrait’s tenderness deepens. The amulets, the quiet face, the dog’s attention—these become foreshadowings of a fate the court hoped to avoid. Yet Velázquez does not imbue the scene with tragedy. He paints a dignified present tense. The boy is alive in a specific hour, the light soft on his forehead, the room warm with red. This stoic commitment to the moment is the painter’s highest ethical stance. He gives the viewer no melodrama to consume, only presence to honor.

Relation To “Las Meninas” And The Late Court Cycle

Executed three years after “Las Meninas,” this portrait shares that masterpiece’s tonal intelligence and moral clarity. In the earlier work, a slightly older princess anchors the court’s social web; here, the prince stands alone, watched by our eyes and a dog’s. The brushwork that turned satin to light in “Las Meninas” now turns infant ruffles to air and tassels to heartbeat-like accents. The quieter scale invites closer looking, and the reward is an intimacy that state images rarely grant.

The Viewer’s Vantage And The Contract Of Regard

We stand at the child’s eye level—perhaps a fraction above—an angle that balances respect with tenderness. The prince does not perform; he allows himself to be seen. The contract is mutual: the viewer owes attention and patience; the sitter offers unsentimental presence. This pact is why the portrait feels modern. It is not a spectacle to be admired from afar; it is a meeting in a shared room.

Paint As Evidence Of Care

The picture’s surface contains its own biography: thin passages in the dark let warm ground breathe; raised touches along the chair’s studs and the jewel-like amulets catch real light; the dog’s fur shows the direction of a bristle’s sweep. These traces of making are not accidents; they are a record of the painter’s attention. To look at them is to perceive care translated into matter, which is ultimately what the painting is about—care for a child, care for a dynasty, and care for the art that preserves both.

The Ethics Of Restraint

It would have been easy to ring the child with allegory or drown him in embroidery. Velázquez opts for restraint. He keeps the palette narrow, places objects only where they serve the likeness, and allows the boy’s face to carry the composition. In this discipline lies both the poetry and the persuasion of the image. The prince does not need grand symbols to project importance; truth presented with clarity is enough.

Lessons For Seeing

The portrait teaches you how to look. Begin with the pinpoint lights in the eyes; notice how they balance the brighter studs on the chair and the softer shine of the amulets. Follow the red seam at the sleeve into the deep red curtain and back down to the carpet’s mottled pattern. Observe the gentle ellipse of the dress at the hem and how its rhythm is echoed in the dog’s rounded back. Let your eyes finally come to rest on the relaxed hand at the boy’s side, a small human sign that steadies the whole room.

Why The Painting Endures

“Prince Philip Prosper” endures not because it is a document of royal propaganda, but because it is a document of attention. The painter’s fidelity to atmosphere, gesture, and light converts fragile biography into lasting presence. The image persuades across centuries exactly as it did at court: by the authority of truth. We recognize the child, we sense the care that surrounds him, and we understand without instruction that the stakes are both personal and historical.

Conclusion

Velázquez’s 1659 portrait of Prince Philip Prosper is a summit of late court painting: a small figure who fills a room by virtue of light, a few calibrated reds, the glint of protective charms, and a gaze that quietly meets our own. Ceremony is here, but it has been softened into human scale. The brush remains visible, the air shared, the moment dignified. Looking at this canvas, we experience what the best portraiture offers—a meeting carried by care, clarity, and the humbling knowledge that presence, not pageantry, is what truly makes a person royal.