Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction: A Portrait that Thinks with Its Hands

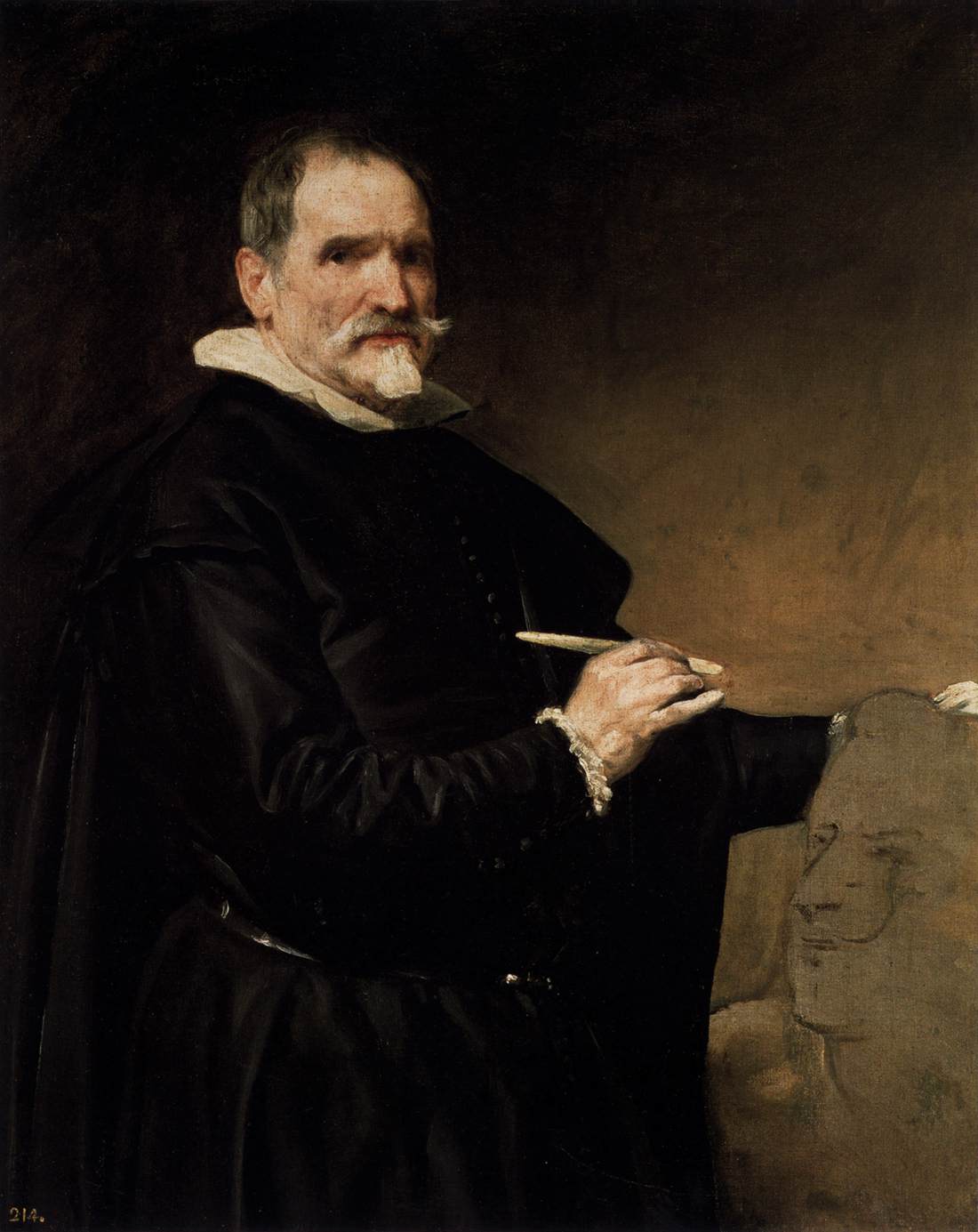

Diego Velázquez’s “Portrait of the Sculptor, Juan Martínez Montañés” stages one of the most intimate encounters in Baroque art: painter and sculptor meeting across media, with the sitter caught mid-gesture as his chisel or modeling tool hovers over a clay or wax head. The background is an atmospheric brown that breathes like studio air; the sculptor’s black habit absorbs light while the lace at his cuffs and collar flashes small clarities; his lined face turns toward us with a look that mingles concentration, patience, and modest pride. Nothing is theatrical, and yet everything is charged. Velázquez refuses courtly pomp and gives us the dignity of work, the nobility of craft, and the intelligence of a hand that has spent decades turning inert matter into living form.

Historical Context: A Meeting of Masters in the Habsburg Orbit

Painted around 1635, the portrait comes from Velázquez’s Madrid maturity, when he had already absorbed the lessons of Italy—tonal unity, pictorial air, and the freedom of painterly synthesis—and re forged them in a Castilian key of restraint. Juan Martínez Montañés, older than Velázquez and already famous in Seville for his polychromed wood sculpture, visited Madrid to model the king’s likeness for a bronze effigy. Velázquez seized the chance to honor the elder master. Instead of presenting him as a grandee decorated with orders, the painter shows the sculptor at work. The gesture is cultural diplomacy and personal homage: a court painter acknowledging that the monarchy’s image depends not only on courtiers and ministers, but also on the makers who give power its durable shapes.

Composition: The Triangle of Head, Hand, and Model

The composition balances three focal nodes. At left, Montañés’s head rises from a dark, voluminous garment; at center, his right hand and tool, rendered with anatomical precision, hover in the light; at right, the half-blocked head of a sculpture emerges from the ground in earthy tones. The triangle they form draws the eye in a circuit—mind to hand to work and back again—so that looking becomes a rehearsal of the sculptor’s own process. The sitter’s torso is turned slightly away, but his head rotates back toward us, storing a reservoir of energy in the neck and shoulders. This slight torsion keeps the image awake; it is a figure caught between concentration and acknowledgement, present to both task and viewer.

The Face: Weathered Authority and Clear Intention

Velázquez maps the sculptor’s face with mild, impartial light that clarifies rather than dramatizes. The forehead carries the pale sheen of thought; crow’s-feet break from the outer eye with the credibility of years; a white moustache and goatee frame a mouth that can turn to kindness or critique without leaving self-command. The eyes are steady, not burning; they look through, not at, the world, as if measuring form against an inner storehouse of knowledge. This quiet psychology aligns with the ethical tone of the portrait: authority born from competence, not from noise.

Hands as Instruments of Mind

In Velázquez, hands speak. Here the right hand becomes the painting’s grammar and heartbeat. Veins lie like pale threads under the skin; the thumb braces the tool; the fingers gather with purposeful delicacy—the grip of someone who understands pressure to the gram. The left hand, mostly submerged in shadow, offers a counter-weight, reinforcing the calm of the pose. The tool itself is no gleaming emblem; it is practical, slightly worn, angled with habitual assurance. By dignifying the workman’s hand, Velázquez dignifies the knowledge that lives in touch, the intelligence that travels from eye to fingertip.

Black as Structure, Lace as Breath

Spanish black is never empty in Velázquez. Montañés’s garment is a grand, dark architecture that shapes space without shouting. Broad, soft passages absorb light to anchor the figure; satin flickers along folds to report movement; seams and buttons are hinted rather than counted. Against this deep mass, the linen collar and lace cuffs operate like windows of air. Their cool whites oxygenate the color system and lift the head from the garment without detaching it from the room’s atmosphere. The economy of these passages—few strokes, exactly placed—keeps the painting alive rather than overfinished.

Pictorial Air and the Ethics of Restraint

The background is a field of warm, modulated browns, brushed with visible energy. It reads as the breathable air of a studio, not as an abstract void. That atmosphere fuses figure and ground, giving the portrait softness at the edges where cloth, flesh, and air meet. The restraint is deliberate. Velázquez avoids props that would literalize biography—no clutter of tools, no sculptor’s bench piled with chips—because he trusts the viewer to grasp the essential. The result is modern in spirit: the fewer the distractions, the clearer the encounter with a person at work.

The Sculpture Within the Painting: Mediums in Conversation

On the right, the emergent head acts like a quotation inside the canvas—a sculpture in the making, sketched with painterly shorthand. Velázquez states planes, hollows, and the outline of the nose with broad, confident strokes, just enough to convey volume and direction. This economy has two effects. First, it honors Montañés’s process, catching the clay at a stage where decisions are still reversible, where mind and hand are negotiating. Second, it sets up a subtle contest and collaboration between mediums: paint modeling sculpture modeling a living head. The hierarchy collapses into conversation, and the viewer sees how different crafts chase the same truth by different paths.

Light as Narrative and Proof

Light is the portrait’s narrator. It picks out the architect’s essentials: the working hand, the small gleam on the tool, the ridge of cheek, the lifespan in the eyes. On the modelled head, light registers the clay’s moistness and the direction of strokes, making material specific without fetish. In the garment, light is slower and broader, revealing weight, depth, and the dignity of volume. These differentiated illuminations constitute proof: proof of presence, proof of work, proof that the world here is optically coherent. The viewer’s belief in the man is secured by the painting’s belief in light.

Brushwork: Suggestion Over Enumeration

Move close and the surface resolves into a language of marks. The beard is laid with a handful of silvery flicks and warm glazes that your eye knits into hair. The collar’s creases are pulled from quick, opaque notes; the cuff lace is a concentrated scrawl, exact at the edges and suggestive in the interior. The tool catches a single high note of highlight at its tip; the clay head is blocked with pooled shadows and lifted planes that snap into legibility at the proper distance. This economy honors the viewer’s intelligence, inviting participation in finishing the picture optically—one reason Velázquez’s portraits never stale.

The Psychology of Work: Pause Inside Flow

Every element serves to dramatize a pause inside continuous action. The sculptor has looked up, perhaps to evaluate or to acknowledge an interruption, while the tool rests in provisional suspension. Because the clay head is still becoming, the painting traps time at a hinge moment when potential is highest. That temporal tension—the “almost”—is profoundly human. Velázquez shows not accomplishment alone, but the disciplined attention that makes accomplishment possible.

Dialogue with Velázquez’s Other Working Portraits

Across the oeuvre, Velázquez honored people at work: jesters with their staffs, a court huntsman whose hands speak readiness, a kitchen maid caught before the Virgin’s apparition, even the painter himself in “Las Meninas.” Montañés joins this company as a master depicted through his practice rather than his social station. Compared with the showy splendor of royal armor and sashes in equestrian portraits, this canvas seems pared back; yet the respect is the same. Velázquez’s democratic exactness extends court dignity to the studio and brings studio truth to the court.

Color as Moral Temperature

The palette is a constrained chord—warm umbers and siennas; cool, almost blue-black in the garment; pearl whites at collar and cuff; flesh built from pinks cooled by grays. The clay head picks up the earth notes and anchors the right side of the field. Because saturation is low, small shifts carry emotion: a blush at the cheek deepens sympathy; a cooler shadow at the temple introduces gravity. Color functions as moral temperature, keeping the picture balanced between warmth (humanity) and cool (discipline).

Edge Behavior and the Reality of Air

Edges here are never mere borders. The shoulder dissolves into the room with a softness that breathes; the contour of the head tightens around the temple and relaxes near the hairline; the knuckles sharpen where light turns abruptly. These micro-decisions keep the image from hardening. The sitter inhabits the same air we do. That unity of figure and ground—learned from Venice, refined by Velázquez—reinforces the portrait’s larger ethic: truth without fuss.

The Intelligence of the Gaze

Montañés’s gaze is unusually complex. It acknowledges our presence, but not at the expense of the work. He looks slightly downward and to the side, a supervisory angle common to craft: measuring the whole while working a part. The expression carries a touch of weariness and a great deal of clarity. It is the look of someone who has made thousands of decisions on hundreds of faces and knows the thousand and first must be as careful as the first. The portrait, in honoring that attention, offers a definition of mastery as a lifetime of well-placed choices.

Material Presence: A Painting That Breathes with the Room

Velázquez engineers the surface to respond to ambient light. Thin scumbles in the background take on the room’s color; denser lights on knuckle, collar, and tool throw back small sparks; the satin passages on the garment open or close as you move. The object is not a static illustration; it behaves like a person seen across time, its meanings re-voiced by changes in illumination. This responsiveness helps explain why the portrait still feels contemporary: it performs with you.

Craft, Status, and the Spanish Ideal of Dignity

Seventeenth-century Spain valued gravity—gravedad—as a public virtue. Velázquez gives that virtue to a maker. By clothing Montañés in sober black, by eliminating distracting emblems, and by elevating the act of work, the painter argues that craft has rank. The court that commissioned armor and sashes also depended on hands and tools; this portrait demonstrates that dependence without sermon. The message is quiet and persuasive: dignity lives in attention to one’s task.

The Sculpted Head as Self-Portrait in Method

Some scholars have proposed that the modeled head relates to the king’s likeness Montañés created in Madrid. Regardless of identity, the clay profile doubles as a metaphorical self-portrait of method. Its half-formed planes mirror the half-described passages in Velázquez’s own painting. Both artists, in different materials, build solidity from layered approximations, trusting that a few right decisions in the right places will conjure life. The portrait thus becomes a manifesto for realism: fewer perfect moves are better than many fussy ones.

Economy Versus Display: Why the Picture Feels Modern

Though created for a world of ceremony, the portrait looks startlingly modern because it declines ceremony. There is no gilded chair, no column, no drape. The room is an idea of a studio, not a catalog of things. The sitter’s identity is inseparable from the act he is performing. Contemporary viewers, accustomed to images of people defined by their doing rather than their having, find here an ancestor. The painting affirms that authenticity—feeling like the truth—is a higher form of splendor than display.

Lessons for Looking: How to Read the Painting Slowly

To understand the picture’s quiet richness, let your gaze follow the triangle repeatedly. Start at the sitter’s eyes, note the tiny window of light in each pupil, then travel to the knuckles and tool. Stay long enough to sense the tension in the grip, the poised pause. Move to the modeled head; allow the broad planes to snap into facial structure; then return to the eyes. Each circuit reveals more: the way lace hardens at the edge and dissolves inward; the covered left hand’s counterweight; the garment’s deep architecture. The portrait rewards attention with attention—the more carefully you look, the more carefully it seems painted.

Why the Portrait Endures

“Portrait of the Sculptor, Juan Martínez Montañés” endures because it reconciles polarities that often break apart: modesty and grandeur, speed and deliberation, surface and depth, person and profession. It is a work about work that itself works exquisitely. It shows how a life of making leaves its map in a face and how a fellow maker can read that map with respect. In times that oscillate between fetishizing celebrity and neglecting skill, the painting remains an antidote—an image of mastery at human scale.

Conclusion: Two Arts, One Truth

Velázquez gives us not merely a likeness of Montañés, but a philosophy of making. Painter and sculptor share methods—a reliance on light, on mass, on edges that tell the truth without shouting—and share a belief that presence can be summoned from humble matter by intelligent hands. The portrait, poised between head, hand, and model, dramatizes that belief with quiet power. It is an homage, a conversation across mediums, and a proposal for what dignity in art looks like: attention, sufficiency, and a confidence that the smallest true mark can carry the weight of a life.