Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

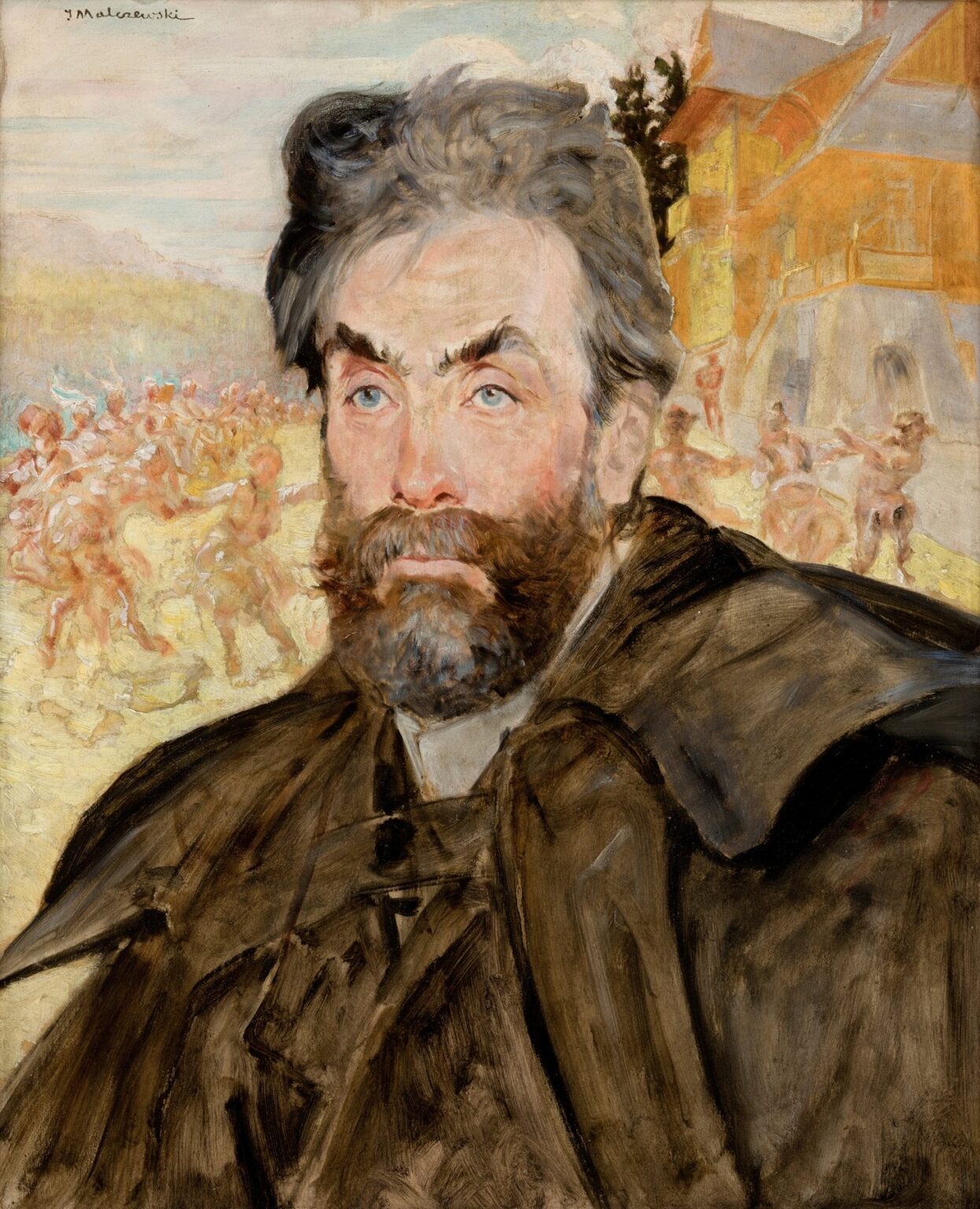

Jacek Malczewski’s Portrait of Stanisław Witkiewicz (1902) stands as a masterful convergence of personal likeness and cultural narrative. At its center is Stanisław Witkiewicz—painter, art theoretician, writer, and the originator of the Zakopane architectural style—rendered with striking immediacy. Behind him, Malczewski unfolds a panoramic tableau of Highlander dancers and vernacular buildings that celebrate Witkiewicz’s devotion to Podhale folk traditions. This portrait is more than a study of character; it is an emblem of Poland’s turn-of-the-century artistic renaissance. Through deliberate composition, a resonant palette, and layered symbolism, Malczewski captures both Witkiewicz’s intellectual vigor and the regional culture he championed. In the sections that follow, we will explore the historical context of the work, examine its compositional and technical strategies, unpack its iconographic depth, and reflect on its psychological and cultural resonance.

Historical and Biographical Context

Stanisław Witkiewicz (1851–1915) emerged as a towering figure in late 19th- and early 20th-century Polish art and culture. Trained in Munich and influenced by European realism and symbolism, he returned to Galicia with the conviction that Poland’s own mountain folk traditions could revitalize national identity under foreign partitions. In 1893 he pioneered the “Zakopane Style” of wooden architecture, translating Highlander motifs into villas and public buildings. As an art critic and novelist, Witkiewicz promoted a synthesis of modernist aesthetics and local vernacular, arguing that true innovation springs from indigenous roots rather than imported fashions. In 1902, when Malczewski painted his portrait, Witkiewicz had already published his influential treatise on regional art and guided a generation of students at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts. Malczewski, a close friend and fellow Young Poland proponent, sought to honor Witkiewicz’s contributions by embedding his likeness within the very cultural landscape he had championed.

The Sitter: Stanisław Witkiewicz

Malczewski’s portrayal of Witkiewicz conveys both the man’s intellectual rigor and his deep empathy for Highlander life. Witkiewicz’s gaze, directed just beyond the viewer’s eye, suggests contemplative foresight—an artist and theorist forever looking ahead toward cultural renewal. His beard and furrowed brow lend gravitas, balancing a subtle warmth in the bright blue of his eyes. He wears a heavy, dark cloak reminiscent of traditional Kierpce garb, connecting him visually to the Highland shepherds he admired. The collar of a white shirt peeks beneath, hinting at his scholarly pursuits. Malczewski’s focus on the sitter’s head and shoulders elevates Witkiewicz to an almost heroic rank, while the soft handling of facial features reflects affection and respect rather than caricature or idealization.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Malczewski arranges the canvas in layered horizontal bands that echo the rising slopes of the Tatra Mountains and the architectural rhythms of Zakopane dwellings. Nearest to the viewer, Witkiewicz’s powerful bust dominates the foreground, creating an intimate encounter. Behind him, a golden sunlit field teems with a throng of Highlander dancers—an homage to the lively folk festivals Witkiewicz helped document. Further back and to the right, the steep roofs and ornate balconies of Zakopane wooden villas rise against a pale sky. This spatial organization achieves a dynamic triangulation: the sitter anchors the composition while the swirling dancers and angular architecture triangulate his cultural sphere. The shifting planes guide the eye from the solidity of the portrait to the collective energy of folk celebration and finally to the permanence of vernacular design.

Color Palette and Light

Malczewski’s palette in this portrait balances earthy warmth with strategic accents. Witkiewicz’s cloak is rendered in deep umber and tactile brushstrokes that capture the weight of wool or fur. His skin glows with rose-tinted highlights and sunlit arcs, suggesting both vitality and sensitivity to alpine light. The dancers’ figures in the midground are painted in lively ochres and corals, their blurred outlines conjuring movement and communal fervor. The architecture behind them shifts to lighter ochre and muted reds, harmonizing with the dancers’ warmth while receding into atmospheric distance. A pale, cool sky—blended grays and soft blues—provides relief and ambient luminosity. Light appears to originate from above and to the left, modeling the sitter’s features and casting gentle shadows that unify form and background. Through subtle modulation of warm and cool tones, Malczewski achieves a sense of cohesive brightness typical of highland midday.

Brushwork and Painterly Technique

In Portrait of Stanisław Witkiewicz, Malczewski deploys varied brushwork to articulate texture, motion, and presence. The sitter’s face and eyes receive meticulous, blended strokes that capture delicate transitions of light and skin. In contrast, the cloak is handled with broad, bold brushstrokes, emphasizing the material’s heft without overworking detail. The dancing figures behind Witkiewicz are painted with quick, energetic dabs of pigment—tiny flourishes that suggest swirling skirts and raised arms rather than literal depiction. Architectural elements at the right merge precise lines for roof edges with looser, more gestural paint for carved wood patterns. The sky and distant hills dissolve into soft washes and blended strokes that recede behind the sharper forms. This interplay of finish and spontaneity imbues the canvas with both immediacy and depth, reinforcing the portrait’s dual focus on individual character and collective tradition.

Symbolism and Iconographic Depth

Malczewski layers his portrait with symbolic references to Witkiewicz’s life work. The dancing Highlanders evoke Witkiewicz’s documentation of folk music, costume, and ritual—elements he believed essential to Poland’s cultural future. Their blurred, sunlit forms suggest the vitality of oral traditions and communal memory. The Zakopane-style architecture behind the dancers stands as a monument to Witkiewicz’s architectural vision: wooden homes that harmonize with mountainous terrain and folk craftsmanship. Witkiewicz’s cloak and serious countenance link him to the region’s shepherds and teachers who preserved local customs. Even the field of golden grass may allude to the harvest cycle, a natural metaphor for cultural renewal and the sowing of ideas. By embedding these motifs into the background, Malczewski transforms the portrait into a multi-layered allegory of artistic devotion and national revitalization.

Psychological Presence and Gesture

Beyond symbolism, the portrait captures Witkiewicz’s psychological presence. His slightly raised eyebrows and alert eyes convey intellectual curiosity and moral seriousness. The turn of his head suggests engagement with forces beyond the canvas—perhaps the roar of dancers or the vision of architectural blueprints. His lips, neither firmly set nor soft, imply measured reflection rather than emotional display. This balance of introspective calm and latent energy reflects Witkiewicz’s dual roles as scholar and cultural advocate. Malczewski’s sensitive modeling of facial planes and the energetic handling of hair and beard amplify this psychological complexity, inviting viewers to sense the man’s inner life as directly as his outward appearance.

The Zakopane Style and Cultural Advocacy

Portraiture rarely offers such direct commentary on architectural theory, yet Malczewski’s background choices commend the Zakopane style as an aesthetic ideal. Witkiewicz’s adoption of highland ornament—sawn wooden shingles, carved balustrades, pitched roofs—represented a break from imported historicism, championing local materials and folk artistry. By placing those translucent buildings behind Witkiewicz’s head, Malczewski asserts the intellectual and moral heights of this regional architecture. The folk dancers in front of the villas tie the cultural continuum together, evoking festivals where music, dance, and built environment converge. In this way, the portrait foregrounds Witkiewicz’s cultural legacy, situating him not only as artist-in-chief of the Zakopane movement but also as a guardian of Polish folk heritage.

Reception and Lasting Impact

Upon its unveiling in Kraków galleries of 1902, Portrait of Stanisław Witkiewicz garnered immediate praise for its technical brilliance and thematic boldness. Critics recognized Malczewski’s gift for uniting portraiture with cultural narrative, noting how the background and figure coalesce into a singular vision of national identity. The portrait became emblematic of Young Poland’s fusion of modernist technique and folk patriotism. In subsequent exhibitions, it was displayed alongside landscapes and mythological works, demonstrating Malczewski’s versatility across genres. Over the 20th century, art historians cited this painting as a key document of Polish modernism, illustrating how portrait artists engaged with broader debates on architecture, folklore, and national self-definition. Its enduring presence in museum collections continues to inspire studies on cultural hybridity and the role of artists as social commentators.

Conclusion

Jacek Malczewski’s Portrait of Stanisław Witkiewicz remains a landmark of Polish art, weaving together individual character, painterly innovation, and cultural advocacy. Through its layered composition, dynamic brushwork, and resonant symbolism, the painting captures both Witkiewicz’s intellectual vigor and his heartfelt dedication to highland folk traditions. The throng of dancers and stylized Zakopane buildings behind the sitter transform the portrait into an allegory of national renewal, celebrating the marriage of modernist technique and vernacular heritage. Over a century since its creation, the work endures as a testament to the power of art to embody both personal likeness and collective aspiration, affirming Malczewski’s lasting impact on Poland’s cultural identity.