Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

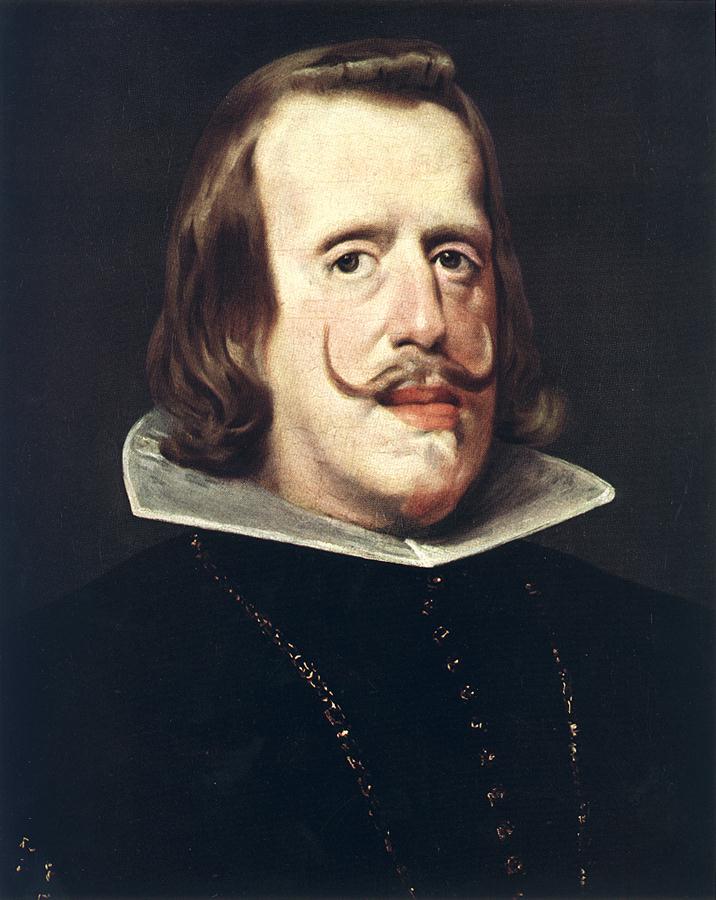

Diego Velázquez’s “Portrait of Philip IV” (1653) condenses decades of collaboration between painter and monarch into a head-and-shoulders likeness of startling immediacy. The king faces us in three-quarter view, his head rising from the bright wedge of a starched collar and the depths of a black costume barely interrupted by the faint sparkle of a chain. The background is an indeterminate air that recedes without distraction. Within this restrained setting, Velázquez achieves an extraordinary mixture of candor and ceremony. The painting bears the weight of state while remaining a human encounter: a tired, alert, and self-aware Philip looks out from behind the mask of kingship, and the picture’s economy of means—tone, temperature, and a handful of decisive strokes—does the rest.

Court, Crisis, and the Late Style of a Painter-King Partnership

By 1653 Philip IV had reigned for more than three decades through wars, territorial losses, and the erosion of Habsburg prestige. Velázquez, his trusted court painter and Aposentador Mayor, had returned from Rome with a liberated brush and a renewed sense of how air and light could construct presence. The king needed portraits that stabilized authority; the painter offered images that stabilized reality. This late likeness compresses that long partnership into a single, lucid statement. It is neither the youthful equestrian glamour of earlier years nor the elaborate pageantry of grand canvases. Instead, it is a sober reckoning—an image tuned to a monarch who had seen the cost of power and who still understood the necessity of appearing.

Composition and the Architecture of Poise

The design is spare and exact. The shoulders form a low base from which the head lifts in quiet dominance. The angled, translucent collar is essential, acting like a luminous wedge that thrusts the face forward while separating it from the dark garment. The body mass is a deep, unified tone that refuses anecdote; the chain’s discreet sparkle articulates depth without clamoring for attention. The head is placed just off center and turned gently toward us. This small torque animates the likeness and creates a dynamic diagonal that runs from the left shoulder through the collar to the forehead, a path our eye travels almost unconsciously. Nothing jars the calm; everything steadies the gaze.

Light, Palette, and the Breathable Dark

Light falls from high left, skimming the brow and ridge of the nose, warming the cheek and upper lip, and then losing strength along the jaw and into the collar’s cool shadow. The palette is Velázquez at his most concentrated: a world of blacks that are never merely black, a collar that is white yet modulates from pearl to chalk to blue-gray, and flesh pitched between warm ochres and restrained roses. The background hovers as a dark air that allows edges to soften and reappear. The painting’s mood—grave but not severe—emerges from these tonal relationships. We feel a room behind the king, but it is defined by breath rather than furniture.

The Face and the Intelligence of Weariness

Velázquez builds Philip’s features with planes of tone, not with hard outline. The brow is a single lucid plane that turns in measured facets; the eyelids sit heavy but focused; the famous Habsburg nose is observed without exaggeration; the lips, shaped by the royal underbite, settle into a line that suggests effort mastered rather than concealed. What makes the portrait modern is the refusal to either flatter or condemn. The painter records fatigue and persistence together. The eyes carry small, bright catches of light that animate the whole; they read as a mind that has learned to listen more than speak. The moustache—calligraphic, controlled—introduces a flourish within restraint, a reminder that kingship remains theater even when the actor is tired.

The Collar as Instrument and Metaphor

Spanish fashion furnished Velázquez with an optical device: the starched, slanted collar. Here it functions like a reflector, lifting light under the chin and pushing the head forward from the engulfing black. Its edges are laid in with crisp strokes that catch actual light in the gallery, turning pigment into the thing depicted. Metaphorically, the collar becomes a civic architecture that props the face of rule. The king’s features emerge not merely from anatomy but from the apparatus of ceremony, and Velázquez makes that apparatus both literal linen and luminous idea.

The Black Costume and the Grammar of Restraint

The garment’s blackness is a declaration of Spanish sobriety, but Velázquez refuses monotony. He orchestrates a spectrum of cool and warm darks: the body takes a soft, velvety black that drinks light; the sleeves and chest flare with barely perceptible sheens; the chain probes the depth like a thin constellation. By denying ornamental distraction, the costume compels attention to the head. The painting thus enacts a political truth: at the center of ceremony stands a person, and the success of the ceremony depends on the credibility of that person’s face.

Brushwork and the Art of Necessary Paint

Up close, the image dissolves into a choreography of exact marks. The hair is a cloud of soft, open strokes over a warm ground; strands are implied with tonal breaks rather than drawn. The collar’s facets are broad planes of cool white, edges snapped with one clean motion. The chain is not counted link by link; metallic flicks become rhythm rather than inventory. Flesh is knit by wet transitions and delicate glazes; the small highlights at the inner corners of the eyes are placed like punctuation, activating the whole sentence of the face. This economy is not parsimony; it is a mature belief that a few right decisions outpace a thousand correct details.

The Habsburg Likeness and Velázquez’s Honesty

Generations of portraitists struggled with the Habsburg physiognomy, especially the mandibular prognathism that could invite either ridicule or erasure. Velázquez always chose the third way: truthful but tempered by air and light. Here the underbite appears, but the head’s turn and the modelling of the lips prevent it from dominating. The painter accepts what heredity gives and registers what reign has required. Because he does not try to beautify, he can dignify. The monarch’s authority grows from candor, not cosmetics.

Background as Moral Space

The undefined dark behind Philip is not a failure to furnish; it is a principle. In this breathable atmosphere Velázquez places everyone—kings, jesters, cardinals, dwarfs, philosophers—on equal terms with the viewer. Within that democracy of air, character must carry rank. The decision is especially powerful in this late royal image. The throne room falls away; the man remains. It is not anti-ceremonial; it is ceremony stripped to its essence: face, light, and the courage to be seen.

From Youthful Majesty to Late Gravitas

Compare this portrait with Velázquez’s earlier images of Philip—the youthful equestrian triumphs, the brocade brilliance, the expansive formats. The 1653 head pares away the world that once surrounded the king. The change is biographical and stylistic. Politically, the crown’s disappointments have accumulated; artistically, the painter’s Roman lessons about economy and atmosphere have ripened. The transformation converts the icon of a regime into a human intelligence at its center. It is not diminution; it is concentration.

The Viewer’s Distance and the Contract of Regard

We meet the king just below eye level, at a distance suited to conversation rather than parade. This vantage constructs a pact of mutual respect. The sitter will not overwhelm us with pageantry; we will attend without prying. The compact is sustained by the picture’s tonality: no violent contrasts, no rhetorical diagonals, only the steady pressure of presence. The viewer feels addressed but not accosted, admitted but not flattered. This balance—courtesy without capitulation—is the secret of Velázquez’s late portraits.

The Subtle Politics of a Chain

The faint glimmer that threads the chest is more than an accessory. It signals office while obeying the painting’s hush. Velázquez refuses to sharpen each link; instead he suggests the chain’s geometry with regulated highlights that rise and fade. The effect is musical: a soft ostinato under the melody of the face. The chain says: this is the king, but the person precedes the regalia. Such subordination of emblem to presence is a hallmark of the painter’s vision.

The Physical Intelligence of Skin and Hair

Velázquez’s portraits persuade because they respect physics as much as psychology. Notice the slight halation where hair lifts from temple, the cool shadow where collar meets jaw, the moist brightness at the lower lip, the dry crossing of light over the moustache. These tiny events coordinate to give the sensation of a living head in air. Material truth—how surfaces take and release light—grounds the more abstract truth of character. Without that physical intelligence, the psychological insight would feel rhetorical. With it, the portrait breathes.

Time, Surface, and the Record of Making

The canvas retains the trace of its creation: thin places where the ground murmurs through, thicker highlights along collar and eye that catch real light, faint craquelure traversing the darks like delicate topography. Velázquez allows these records to remain, insisting that a painted truth includes the truth of paint. As the years pass, the surface keeps company with the life it holds; the portrait becomes at once artifact and encounter.

Dialogues Within Velázquez’s Oeuvre

Placed beside contemporary works—“Juan de Pareja,” the Roman papal portraits, the late self-portraits—the “Portrait of Philip IV” participates in a shared tonal universe. Each figure stands in breathable dark, each head is pushed forward by a keyed collar or scarf, each pair of eyes engages us with a different temperature of attention. Yet the king’s likeness is uniquely calm. Where Innocent X tests the viewer with suspicious intelligence, Philip meets us with measured endurance. The painter calibrates this difference not with overt gesture but with micro-choices of value, edge, and temperature.

The Modernity of Restraint

The painting reads as modern because it refuses both moralism and spectacle. It treats power as a person in light, not as a costume on a platform. Its visible brushwork anticipates later painters—Goya, Manet, Sargent—who would trust atmosphere and touch over emblem. In a visual culture flooded with declarative images of leadership, Velázquez’s quiet proves radical. The king does not dominate; he persists. The portrait asserts that endurance, rendered exactly, is a form of grandeur.

Why the Likeness Endures

This picture endures because it solves a complex equation with elegance. It honors the requirements of state portraiture while remaining psychologically exact. It satisfies the eye with tactile truth—hair, skin, linen—while letting the mind recognize a fellow consciousness. It is spare without being thin, generous without being indulgent. Most of all, it demonstrates how a small set of elements—head, collar, dark air—can carry the entire weight of history when they are arranged by a painter who trusts truth more than ornament.

Conclusion

“Portrait of Philip IV” is the distilled essence of Velázquez’s royal portraiture. A head rises from luminous linen and sober black; light clarifies planes of flesh; a chain whispers rank; a dark air equalizes the encounter. Within this near-minimal structure, the king’s humanity appears—aware, burdened, enduring. The painter’s late mastery is everywhere: brushwork that states only what is necessary, a palette tuned by temperature rather than hue, and an ethic that treats presence as the highest form of dignity. Four centuries on, the picture still asks for nothing but attention and repays it with a living exchange: a monarch who has become, through the exactness of art, simply and unforgettably a man.