Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

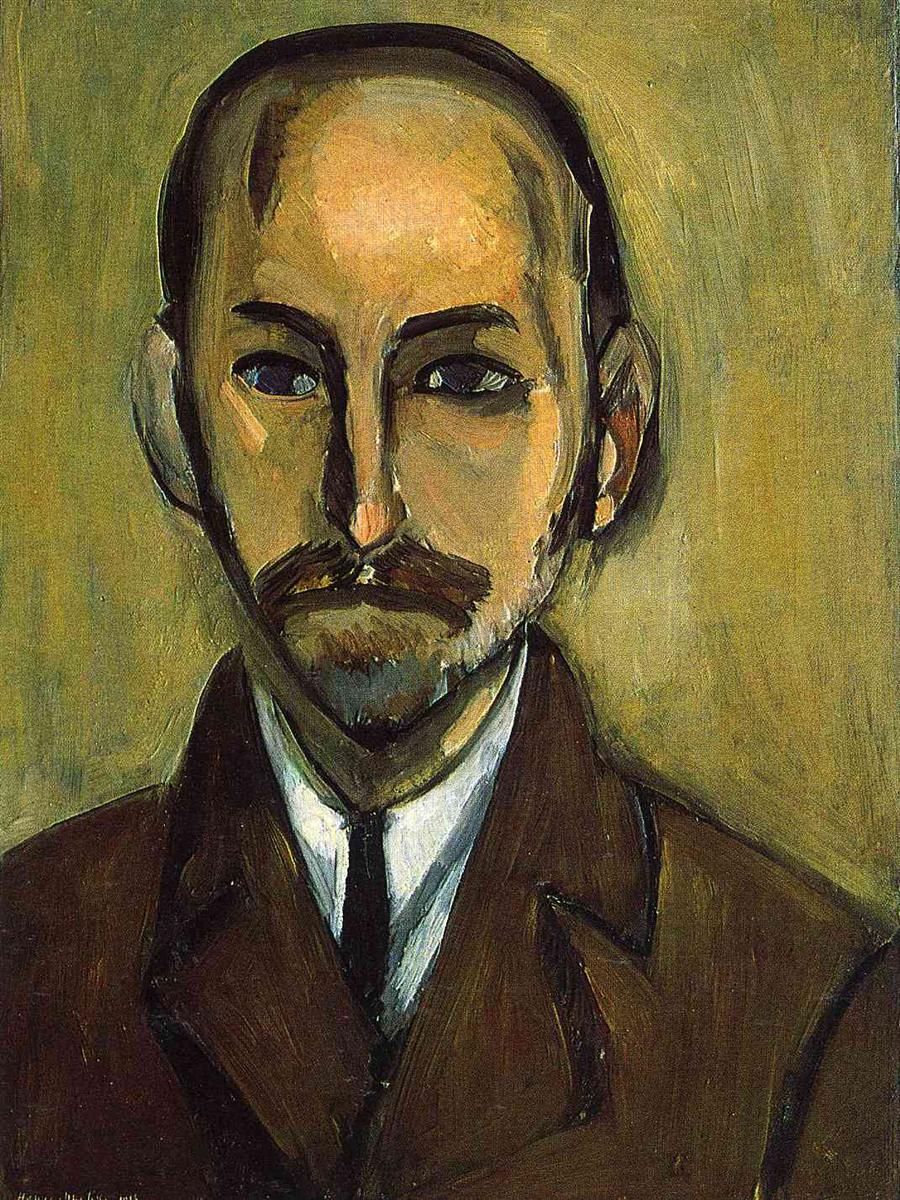

Henri Matisse’s “Portrait of Michael Stein” (1916) is a compact, frontal likeness that turns the grammar of modern painting into a study of character. The sitter faces us squarely, his high forehead catching light, his eyes set beneath strong brows, his beard shaping a dark triangle above a narrow tie. Everything around him reduces to essential planes: a jacket rendered as deep brown slabs, a neutral ground flickering between olive and straw, a collar and shirt simplified to tapering wedges of white. With very few colors and a disciplined contour, Matisse constructs a portrait that is simultaneously direct and deeply meditated—a summation of his wartime search for order and a tribute to one of his earliest and most loyal patrons.

Historical Context and Patronage

Between 1914 and 1917, Matisse’s painting changed dramatically. The dazzling chromatic eruptions of Fauvism gave way to a spare language of large color fields, powerful outlines, and carefully controlled value. Paris, under the strain of World War I, provided a somber backdrop to this internal tightening. During these years Matisse made a number of portraits of close associates and patrons, using their faces to test a more structural, architectonic approach.

Michael Stein—brother of writer Gertrude Stein and an ardent collector with his wife Sarah—had been championing Matisse for over a decade. Their apartment in Paris was a sanctuary for the artist’s work; their faith helped stabilize his career after critical storms. In the 1916 portrait Matisse returns the favor, not by flattering the patron with decorative opulence, but by honoring him with clarity, sobriety, and a steady, almost contemplative gaze. The painting becomes both likeness and manifesto: here is the man who believed in the work, presented in the very language that belief enabled.

First Impressions and Composition

Seen at a glance, the portrait is built on a system of nested triangles and ovals that lock the image into the rectangle. The bald dome of the head forms a luminous oval, the beard and tie create a dark triangle, and the lapels of the jacket articulate counter-triangles pointing outward. The shoulders push to the canvas edges, giving the bust the scale of a relief. The entire composition hinges on the vertical axis of nose, beard, and tie, offset by the oblique lapel lines and the gentle tilt of the head.

Matisse positions the sitter close to the picture plane. The background is shallow and unparticular; it acts as atmosphere rather than space. That compression yields intensity: we confront a person, not an anecdotal setting. The proximity lets the modeling of eyes, cheeks, and mouth operate at the center of attention, while the rest of the figure is simplified to near-abstract forms.

A Restricted, Expressive Palette

Color is austere and purposeful. Earth browns, olive-yellows, and charcoal-black carry most of the picture, with small reserves of white in the shirt and two tiny sparks within the eyes. The browns are not singular; they step from roasted umber to chestnut to a smoky, nearly black mixture at the beard and lapels. The background’s yellow-green keeps the head warm and alive, while its cooler notes keep the painting from becoming monochrome.

This rationed palette has consequences for mood and structure. It introduces the gravity appropriate to a portrait made in wartime. It also allows minute temperature shifts—warmer around the forehead, cooler in the cheek shadows—to do the work that saturated color once did in Matisse’s Fauvist canvases. In “Portrait of Michael Stein,” warmth and coolness replace high-chroma contrasts as the chief expressive tools.

The Authority of Contour

A supple, elastic contour holds the portrait together. Matisse’s line is neither fussy nor mechanical. It thickens along the collar to assert a ridge, softens around the ears where flesh yields to shadow, and sharpens at the nose to cut the mask-like face from the surrounding air. Around the eyes, a few angular strokes establish lids and brow ridges; around the beard, broken lines let painted hair merge into the skin’s edge.

This contour is more than description. It organizes. It parcels the head into legible planes and binds the jacket’s great brown fields into a single, architectural form. Even when the brushwork inside those shapes becomes loose or scumbled, the contour maintains coherence, allowing interior freedom without sacrificing design.

Faceted Planes and the Legacy of Cézanne

The face is shaped not by soft illusionistic modeling but by interlocking planes. A warm wedge at the forehead meets a cooler, violet-gray patch at the temple; the cheek turns with a flat brushstroke that declares its direction; the nose bridge is a simple, vertical plane bracketed by darker passages. These facets echo Matisse’s dialogue with Cézanne, whose late portraits taught a generation how to turn flesh into planes that hold the picture surface.

This planar construction gives the portrait structural credibility. The head feels solid beneath the skin, the beard reads as a mass that sits on the jaw, the eye sockets carve inward. Yet nothing becomes academic; the facets are kept broad and alive, and where a plane might become brittle, Matisse tempers it with a drag of the brush or a translucent glaze.

The Background as Climate

The ground is a mutable olive field stained with yellow ocher and gray-green. It swirls lightly, a visible record of broad brushstrokes that leave the canvas’s weave breathing. The ground carries a middle value that does two jobs: it lets the dark beard and lapels register powerfully and it keeps the high forehead luminous without blasting to pure white. The smudged halo around the ears and shoulders suggests that the head was shifted slightly during work—small pentimenti that keep the surface alive and mark the portrait as an achieved decision rather than a neat design imposed all at once.

Light and Value Strategy

Rather than dramatizing the sitter with theatrical shadows, Matisse redistributes illumination to clarify form. The forehead and nose catch the highest lights; cheek hollows and the eye sockets sink by a step or two; the beard and tie anchor the lower range of values. This calibrated scale brings the face forward and lets the jacket remain a larger, quieter base. Because the range is controlled, the smallest highlights—along the lower lip or the eye’s wet rim—suddenly matter, quickening the likeness with minimal means.

Brushwork and Surface

Up close, the paint handling reveals great variety. In the jacket, long strokes follow the seams of the lapel and the drop of the shoulder, with darker threads dragged wet-in-wet to mimic the slight sheen of wool. In the face, shorter strokes knit together to articulate bone and muscle; some passages are nearly dry-brushed, leaving warmer underpaint visible. The beard is built with directional marks that point down and in, creating both texture and gravity. In the background, soft circular scrubs are left unpolished, preserving the studio’s air and the hand’s labor.

This refusal of immaculate finish is not negligence; it is a commitment to truth and vitality. The surface is allowed to speak as painting, reminding the viewer that clarity need not cancel touch.

Eyes and Psychological Presence

The portrait’s psychology concentrates in the eyes. They are not hyper-described; they are constructed with two or three planes and capped by strong brows. Yet the oblique catchlights, the dark irises, and the small compressions around the lids deliver presence with remarkable force. The gaze is steady, slightly inward, as if the sitter meets the painter’s concentration with his own. There is also quiet warmth in the slight swell of the cheek and the softening of the mouth beneath the mustache—signals of a person whose intellect does not eclipse human gentleness.

Dress, Tie, and the Ethic of Sobriety

The brown suit, white shirt, and dark tie are rendered with monumental simplicity. They build the stern base on which the bright head rests. The tie’s narrow wedge parallels the nose and beard triangle, strengthening the vertical axis and compressing the composition’s energy toward the center. Such sobriety also reads as a moral stance. In a period of upheaval and rationing, surfaces that once invited ornament become occasions for restraint. The patron who supported radical color is pictured in a uniform of modern seriousness, suggesting his own steadiness and Matisse’s respect.

Relation to Contemporary Portraits

Placed beside portraits like “Greta Prozor,” “Laurette with Long Locks,” or “The Italian Woman,” this canvas shows the range of Matisse’s experiments in 1916. The masklike emphasis of the brows and nose relates it to those works, as does the planar construction of the head. But the palette here is even more reduced, the design more symmetrical, the rhetoric more sober. Where the Laurette pictures play with costuming and sensual fabric, “Portrait of Michael Stein” strips away accessory and makes the man himself the whole subject. It is a quintessential patron’s portrait, modern in language and classical in dignity.

Influences Without Quotation

Viewers sometimes sense in Matisse’s wartime faces the gravity of Byzantine icons or the distilled power of African sculpture. In this painting those influences have been fully absorbed: the frontal pose and the centralized head echo the icon’s authority; the simplification of features speaks to the sculptural idea of a mask. But the painting never lapses into pastiche. It remains resolutely contemporary, addressed to the flat plane of a modern canvas and spoken in Matisse’s unmistakable voice.

Process, Adjustments, and Pentimenti

There are subtle signs of revision that reward close looking. A half-halo around the right ear suggests the head shifted a few millimeters; a darker seam beneath the lapel hints that the contour was tightened after the interior planes were laid. In the ground, small, warmer stains surface through later cool strokes, evidence of the painter’s search for the exact temperature that would keep the head alive. These traces complicate the apparent simplicity and remind us that such clarity is not schematic but discovered.

How to Look

Begin with the whole: the high, lit forehead; the dark triangle of beard and tie; the jacket’s broad brown architecture. Let your eye travel along the vertical axis and then out along the lapels to the shoulders. Step closer to read the face’s planes and the painterly variety that joins them. Notice the few strokes that define an eye, the quick notches that turn nostril and ear, the delicate translucency of the skin over cheekbone. Return to distance so that particulars dissolve back into a single, decisive presence. The oscillation between structure and touch, between the icon-like and the human, is the portrait’s heartbeat.

Meaning and Legacy

“Portrait of Michael Stein” offers more than likeness; it embodies a way of seeing that influenced generations. It proves that modernism’s reduction need not strip away personality and that restrained palettes can be eloquent. In honoring a patron with such a disciplined image, Matisse also honors painting itself—its capacity to carry psychological nuance through a handful of colors and lines. The picture stands as a testament to the intimate grandeur possible when a great artist meets a devoted friend and collector.

Conclusion

This portrait compresses a remarkable amount of thought and feeling into a tight frame. Its planes are clear, its palette frugal, its contour commanding. Yet the man who looks back at us is not an abstraction. He is attentive, serious, and alive, his presence hovering between the formal and the familiar. In the difficult middle years of the 1910s, Matisse found a way to fuse modern structure with human warmth. “Portrait of Michael Stein” remains one of the purest statements of that fusion—an image of steadiness forged from the simplest elements of painting.