Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to “Portrait of George Besson” (1917)

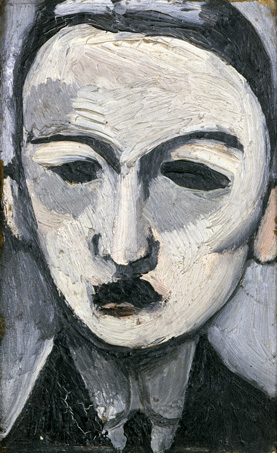

Henri Matisse’s “Portrait of George Besson” is one of those small, concentrated canvases that feels larger than its dimensions. With a palette reduced almost to bones—chalky whites, slate grays, and dense blacks—Matisse delivers a head that is at once human and mask-like, intimate and impersonal. The sitter’s eyes are heavy caverns of shadow; a neat dark moustache anchors the mouth; the suit is a wedge of black that tapers toward the bottom of the panel. Everything is simplified to essentials, yet nothing is careless. Painted in 1917, at the very threshold of Matisse’s Nice period, the portrait captures a shift in his practice: after a decade of blazing color and pattern, he turns to an austere language of planes and strokes to test how much a face can be reduced and still throb with presence.

Who George Besson Was and Why He Mattered to Matisse

George Besson was a French art critic, collector, and champion of modern painting. He and his wife, Adèle, formed a collection that later entered public institutions and played a significant role in shaping French taste for the avant-garde. Besson wrote persuasively in defense of contemporary artists, and Matisse counted him among the allies who truly understood his ambitions. The portrait, then, is not a commission in a conventional sense but a token of collegial recognition. Matisse does not flatter. He distills. In place of polite likeness, he offers a statement about vision: a critic represented by a head that reads like a carved thought.

A Composition Built on Vertical Compression

The first shock of the painting is its format. It is a narrow vertical that compresses the head against the picture plane. The forehead barely fits; the chin nearly spills off the bottom edge. That compression forces attention onto the essential relationships of features—brow to eye socket, nose bridge to nostril, moustache to mouth—while increasing the sense of monumentality. The head becomes a column, a small totem. The suit and tie are condensed into a dark triangle that props the head like a plinth. With almost no background and no anecdotal details, the entire drama occurs in the face’s architecture.

A Palette Reduced to Stone and Bone

Matisse restricts his colors with uncommon rigor. The flesh is a stack of cool and warm whites knifed with gray; the shadows slide toward blue; lines and accents are built from mixtures so dark they read as black. A faint ruddy note appears in the ears and lip, but it is subordinate, a whisper of blood in an otherwise mineral construction. This near-grisaille is not a retreat from color so much as a test of its necessity. After years of orchestral chroma, Matisse asks what can be said with three or four notes. The answer is: a lot. The limited palette clarifies form, brings brushwork forward, and charges every small temperature shift with meaning.

Brushwork that Carries Structure

Look at the forehead: broad, diagonal strokes ride across its dome like wind on snow. At the bridge of the nose, the paint direction changes to vertical, cinching the form and driving the gaze downward. Along the cheeks, strokes break and turn, articulating plane changes without resorting to blended modeling. In the eye sockets, short, loaded touches build darkness with palpable density; in the moustache, a single pass establishes both texture and weight. Matisse’s brush is not descriptive in a photographic sense; it is structural. Each mark is both an analytic decision and a record of movement. The head seems carved from paint.

The Face as Mask and the Mask as Psychology

Because the eyes and mouth are simplified almost to signs, the portrait flirts with anonymity. Yet the result is not cold. The mask-like reduction—deep sockets, compact nose, tight moustache—concentrates rather than erases personality. The sitter appears grave, self-contained, perhaps a little ascetic; the trimmed moustache and the straight fall of the hair imply discipline. Matisse uses impersonal forms to communicate inwardness. The paradox is crucial: by withdrawing anecdotal charm, he makes the head feel inevitable, as if it had been waiting in the paint all along.

The Positive Power of Black

Black in Matisse is never mere absence. Here, as in his best portraits, it acts like a color with its own temperature and light. The jacket wedges upward like a block of onyx; the pupils and moustache absorb light yet gleam at their edges where they meet lighter planes. Thin black rhythms around the lids and nostrils are decisive. They do not outline so much as command. This positive black—at once graphic and luminous—binds the portrait’s cool whites and grays, giving the image its authority.

Cropping, Scale, and Monumentality

Although the painting is small, it feels monumental. That effect comes from three decisions: the extreme cropping, the vertical format, and the refusal of background depth. By pressing the head forward and stripping away spatial cues, Matisse enlarges the sitter’s presence. The portrait behaves like a relief sculpture mounted on the wall. You do not enter it; it arrives at you. This immediacy suits the subject—a critic whose work was to look and judge. The head becomes an instrument of attention.

Between Fauvism and Nice: The Importance of 1917

The date—1917—places the work at a hinge in Matisse’s development. The wild harmonies of the Fauves had matured into a language where color still carried structure but no longer needed to shout. In the late 1910s Matisse experimented with heightened drawing, austerity, and a certain classical severity. Almost immediately after this period he would settle in Nice, where sunlit interiors and patterned fabrics tempered his discipline with atmosphere. The Besson portrait stands precisely in that transition: hard, economical, surgical in its simplification, yet already sensitive to the soft temperatures that would suffuse his Nice canvases. It is a bridge from fire to light.

Dialogue with Earlier Portrait Traditions

Matisse was a revolutionary who knew his ancestors. In this portrait you can feel the moral weight of Ingres’s line, the structural logic of Cézanne’s planes, and the frontal, hieratic solemnity of African masks and medieval icons. None of these influences appear as quotation. They are absorbed into a modern syntax where contour confers dignity, planes construct volume without fuss, and frontal symmetry delivers calm. The painting is modern not because it rejects history but because it recomposes it for new ends.

The Role of Asymmetry and Small Instabilities

Within the tight symmetry of the head, small asymmetries keep the portrait alive. One eye socket sits fractionally higher; the moustache leans a hint to one side; the ear shapes differ. The jawline tightens more sharply on the right than the left. These minute instabilities are not mistakes; they are the signs of looking. They break rigidity and let the face breathe. Matisse understands that a perfect mask is dead, while a human face always carries tiny discrepancies that register as life.

Materiality and the Ethics of the Stroke

Matisse believed in leaving a stroke true to itself. The Besson portrait is a small manifesto of that ethic. Paint is not smeared to invisibility; neither is it heaped into virtuoso ridges for their own sake. Each zone is handled according to its structural task: broader on the forehead to communicate mass, more angular on the nose to signal plane changes, denser in the shadows to weigh them down. The portrait insists that painting is not just picture-making but a form of thought enacted in the material. You can trace the thinking in the surface.

The Suit, Tie, and Social Persona

The sliver of tie, the dark lapels, and the high white shirtfront carry more than costume. They represent the public persona of a critic—formal, tidy, compressed. By rendering them as abstract wedges rather than tailored detail, Matisse treats social identity as shape and value rather than as fashion note. The result is respectful without being deferential. The clothes ground the head but do not compete with it. They are the visible grammar of a professional life reduced to its punctuation marks.

Light, Shadow, and the Space of the Skull

One of the portrait’s quiet marvels is how convincingly it constructs the skull with such reduced means. The forehead bulges not because it is carefully shaded but because strokes change direction and temperature as they cross it; the eye sockets sink because darker mixtures pool there with edges that taper rather than harden; the nose projects because two flanking planes cool relative to the central bridge. These are economical solutions to sculptural problems. The head breathes in shallow space, neither flat nor theatrically deep, but held just in front of the picture plane.

Psychology Without Anecdote

Many portraits lean on props—books, desks, backdrops—to imply character. Matisse refuses those aids. The painting’s psychological charge arises from a handful of visual facts: the gravity of the sockets, the discipline of the mouth, the tight-drawn planes of cheeks and nose. From these he creates a presence that feels thoughtful, serious, and touch inward. The effect is dignified rather than flattering. It suggests a person who looks hard and says little—a critic’s face, pared to function.

Comparisons with Matisse’s Other Portraits of the Period

Placed alongside the portraits of Laurette from 1916–1917, the Besson head looks severe. Laurette’s portraits tend toward warm grounds and lyrical hair; Besson’s is a sculpted block of cool light. Both, however, share the drive toward reduction: big planes, strategic blacks, and a refusal of superfluous description. In that sense, the Besson portrait is the steely end of a spectrum. It demonstrates how Matisse could bend the same formal vocabulary toward very different emotional weather.

The Intimacy of Scale

Small paintings are easy to overlook in reproductions, but scale matters deeply here. At close range, the Besson portrait engages you almost at face-to-face distance. The brushwork reads like handwriting—letters in which pressure and slant carry feeling. You move across the surface from brow to nose in one breath, then pause in the density of the eyes, then feel the quick flick that became a nostril or lip corner. This intimacy of viewing is part of the portrait’s power: it asks the same focused attention from us that a good critic gives to art.

The Image as Modern Icon

Because of its frontality, narrow format, and high-contrast design, the painting bears a faint kinship to icons. It is not religious, but it has the calm authority icons cultivate. Matisse harnesses that authority to secular ends, producing an image that honors the vocation of looking and judging. The face becomes emblematic of scrutiny—an icon of critical seeing.

Why the Portrait Feels Contemporary

A century on, the Besson portrait still looks startlingly fresh. Its compressed palette aligns with contemporary taste for graphic clarity; its impastoed surface satisfies a hunger for visible process; its mask-like geometry anticipates the ways modern artists and designers turn faces into signs. In an era that often strips images down for legibility on screens, Matisse’s reduction reads as prescient rather than austere. The portrait speaks fluently in today’s visual language without surrendering its historical depth.

Enduring Significance in Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Portrait of George Besson” occupies a precise and important slot in Matisse’s development. It proves that after Fauvism’s chromatic revolution he could still discover new force by limiting himself. It demonstrates a route from expression through color to expression through structure. It also pays quiet homage to a critic whose advocacy mattered, not by rendering his likeness sweetly but by giving him the dignity of a distilled, durable form. For viewers mapping Matisse’s trajectory, the painting is a touchstone: the moment when a master of color proves equally a master of value and plane.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s portrait of George Besson is small, cool, and unyieldingly precise. With three or four colors and a handful of decisive strokes, he builds a head that feels carved from light and shadow. The eyes are caverns, the moustache a single authoritative mark, the suit a dark plinth; together they make a modern icon of attention. Set at the threshold of his Nice period, the painting shows an artist retooling his language without losing his voice. It also honors its sitter by granting him what critics prize most: clarity. The image lingers not as a biographical likeness but as a statement about what painting can be when it refuses excess and trusts the intelligence of the stroke.