Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

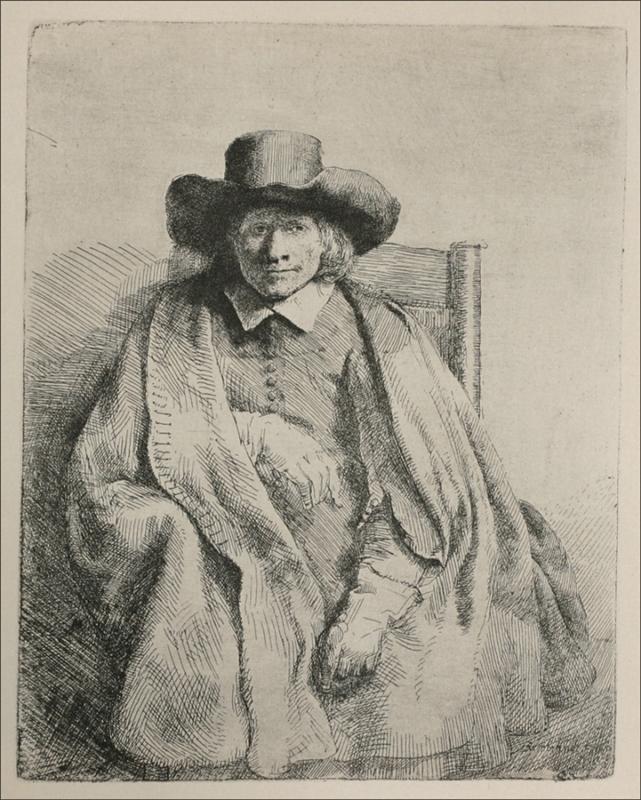

Rembrandt’s “Portrait of Clement de Jonge” presents a seated man whose quiet authority seems to flow as much from his occupation as from his person. Made in 1651, this print captures Clement de Jonge (often modernized as Clement de Jonghe), one of Amsterdam’s successful print dealers and publishers. The sitter belongs to the world that sustained Rembrandt’s own graphic art: the showroom, the stockroom, the market stall, the collector’s cabinet. In this etching and drypoint, Rembrandt turns a habitual business relationship into an absorbing psychological encounter. The man’s hat casts a mild shadow across his brow; his cloak falls in heavy folds; a gloved hand rests, half-clenched; and his gaze, steady and appraising, meets ours with the professional attention of a person used to looking closely.

Subject, Vocation, And The Marketplace Of Prints

Clement de Jonge was not a patrician magistrate or a gilded courtier. He was a merchant of images, someone who bought, commissioned, and distributed engraved and etched sheets to a thriving Dutch public. By representing a print dealer with the gravity usually reserved for scholars or wealthy burghers, Rembrandt elevates the commerce of art to the realm of cultural stewardship. The portrait salutes the man who brings images to the hands of others. The sitter’s demeanor—calm, astute, neither deferential nor vain—reflects a profession grounded in judgment. The tilt of his head and the level gaze suggest an eye trained to evaluate crisp lines, strong impressions, and successful compositions. We sense the invisible presence of portfolios, drawers, and copperplates beyond the frame.

Composition And The Architecture Of Stillness

The composition is starkly frontal. Clement sits squarely before us in a straight-backed chair whose crossbar anchors the right side of the image. He is set a little low within the rectangle, so that the seat and cloak occupy a deep foreground, enlarging his physical presence while keeping the head modestly scaled. The sides of the coat sweep down like heavy curtains and meet near the center in a deep, vertical fold. That long seam, supported by echoing folds to either side, converts fabric into a monumental architecture. Within this mass, the triangle of white collar and the ellipse of the hat form a concentric frame around the face. The arrangement creates a feeling of stilled time. There is no fidgeting or flourish; rather, the sitter settles into his authority, the way a craftsman settles into a bench.

The Language Of Etching And Drypoint

Rembrandt’s line is both descriptive and atmospheric. He builds the cloak with long, parallel hatchings that follow the drape and weight of the wool. In the shadowed recesses, drypoint burr velvets the black, making the fabric feel thick and handled. The chair’s uprights are defined by rectilinear strokes that contrast with the cloak’s curves, keeping the figure from dissolving into shapelessness. Around the hat and face, lines become quieter and more measured; cross-hatching softens to cultivate a bloom of mid-tone. These modulations are not merely technical feats: they assert the sitter’s material reality and touch upon the sensual allure of prints themselves—the way ink clings to plate and deposits gradations that painting cannot exactly replicate.

Light, Tone, And The Intimacy Of Air

Light falls from above and slightly left, striking the top of the hat, the ridge of the cheek, and the edges of the collar. The tonal range is controlled rather than theatrical. Rembrandt declines deep chiaroscuro; instead he lets the face emerge from a matrix of soft greys, as if we have stepped into a showroom lit by a high window. This moderation of contrast suits the subject. A print seller requires clarity, not drama. The print’s air feels breathable, like the atmosphere of a place where one might leaf through portfolios while exchanging learned remarks.

Costume And Status Without Glitter

Clothing plays a crucial part in the portrait’s rhetoric. The broad-brimmed hat belongs to a professional urban type, practical and slightly archaic in fashion. The cloak, voluminous yet unostentatious, swallows ornament and asserts presence through mass, texture, and fall rather than through lace or brocade. The small ruff and line of buttons introduce order at the center, aligning with the sitter’s measured temperament. Rembrandt’s interest lies not in display but in use. These garments are the uniform of someone who spends days in a shop or office, greeting clients, negotiating prices, and caring for stock.

Hands, Gesture, And The Grammar Of Appraisal

Few artists rival Rembrandt in the expressive power of hands. Here, the gloved right hand rests on the knee, the index finger subtly extended as if marking a point in conversation or indicating a sheet set aside for later review. The left hand, partly obscured by the cloak, seems relaxed but ready, a dealer’s hand that might lift a print by its corners to angle it toward light. The gloves themselves suggest daily handling of paper—both practical and symbolic. They keep ink and oil from smudging impressions; they also declare that these objects, though reproducible, are precious. The sitter’s bodily language halts between repose and intention, creating the sense that we have interrupted him during work.

Psychology In The Gaze

The portrait’s quiet magnetism resides in the gaze. Clement does not look past us; he looks at us, and the look is steady. It is not the penetrating stare of a magistrate, nor the bashful glance of a novice; it is the assessing regard of a professional. The mouth is slightly pursed, a sign of attention rather than severity. This is someone used to holding silence while a buyer debates with himself, then returning with a cool price and a better impression when the moment requires. Rembrandt renders this mental poise without caricature. He gives us a human face at work.

Space, Chair, And The Edge Of The Room

The chair’s high crossbar makes a frame within the frame, an architectural punctuation that keeps the sitter bodily present. The left side of the print fades into loose hatching, and the upper background remains bright and open, as if the wall is a blank sheet awaiting the next print to be tacked up for inspection. The uncluttered space honors the sitter’s vocation by refusing anecdote. Nothing distracts from the transactional intimacy between subject and viewer.

The Relationship Between Artist And Dealer

Choosing a print dealer as a subject carries a personal dimension. Rembrandt depended on such men for the circulation of his etchings, for payments, and for gossip within the trade. A successful dealer could make or stall an artist’s market. The portrait’s dignity may thus be read as gratitude and professional respect. At the same time, there is a subtle equality implied. Rembrandt grants the dealer the same weight he offers scholars, Mennonite elders, and wealthy patrons in other portraits. The artist who expanded the expressive range of prints honors the merchant who expanded their audience.

Material Presence And The Truth Of Surfaces

Rembrandt’s handling of cloth is almost geological. The cloak’s strata of hatchings pile up like sediment, each layer catching light differently. The cuffs, hat brim, and the small collar register as distinct materials without resorting to fussy detail. He disdains the ornamental habit of enumerating threads, preferring to orchestrate masses and accents that let the mind fill in texture. The face, by contrast, is built with delicate, searching lines that thicken around the eyelids and mouth, preserving the moist, complex surface of skin. The coordination of these treatments—coarse for fabric, tender for flesh—produces tactile truth.

The Print As Object And Aura

This work is itself a printed multiple, yet it behaves like a singular encounter. That paradox is key to Rembrandt’s printmaking. He used etching and drypoint not to standardize likeness but to stage each impression as a slightly different performance. Variations in inking and wiping can deepen shadows, clarify edges, or soften transitions. A dealer like Clement would have recognized the value of such variety; indeed, he might have had a hand in selecting impressions for favored clients. The portrait embodies the aura of the printed object at a moment when prints were both commodities and vessels of intimacy.

The Culture Of Looking And The Ethics Of Attention

The Dutch Republic’s visual culture prized looking as a civic habit. Markets overflowed with maps, views, portraits, emblematic sheets, and news prints. A dealer nurtured and directed this appetite. Rembrandt’s portrait participates in that culture by modeling attention. The sitter is doing what the viewer does: examining, measuring, and weighing. The image becomes reciprocal—the dealer looks at us as we look at him—and in that exchange the ethics of the trade emerge. Trust depends on mutual recognition. The calm clarity of the portrait, its absence of theatrical flourish, its insistence on sober substance, all speak to an economy where reputation matters.

Time, Aging, And Human Scale

Rembrandt loved faces that register time. Clement’s is not lined in spectacle, but it carries the soft wear of middle age: slightly pouchy eyes, a mouth that has learned restraint, hair peeking beneath the hat brim with the dry frizz of years. The portrait refuses flattery, but it also refuses cruelty. It grants the sitter a human scale in which experience reads as competence rather than loss. Such dignity is part of Rembrandt’s broader humanism.

Comparisons Within Rembrandt’s Portraiture

Placed alongside Rembrandt’s portraits of scholars, Mennonite preachers, and burghers, Clement’s likeness shares key traits: a centered presence, a restricted palette of tones, and a preference for psychological specificity over emblematic pose. It is less grand than the painted portraits and more intimate than some etched heads. Its closest kin are other prints from the early 1650s in which Rembrandt explores seated figures wrapped in capacious garments, their bodies anchored by mass while their faces hover in a bright, habitable atmosphere. Within that family, Clement stands out for the professional modernity of his type: a dealer rather than a gentleman.

Reading The Cloak As Composition

The cloak is more than clothing; it is the compositional machine. The cascading folds build a downward energy that is checked by the hand and the chair’s uprights, stabilizing the figure. The long central seam forms a plumb line that subtly echoes the axis of the face. Triangular areas of slight darkness at the bottom corners frame and lift the mass so that it does not slump. These calculations are barely felt as artifice; they ride under the portrait’s naturalness. But they are why the image holds together with such serene coherence.

The Viewer’s Position And The Ethics Of Encounter

We are seated opposite Clement, at the distance of conversation, and slightly below eye level. The perspective produces courtesy rather than confrontation. There is no pedestal. The portrait invites the kind of exchange that would occur across a table when a portfolio is opened and the top sheet—perhaps a fresh impression of an etching—is gently slid forward. Rembrandt places the viewer inside a social ritual of looking, choosing, and valuing. The intimacy underscores the mutual dependence of artist, dealer, and collector within Amsterdam’s print economy.

Legacy And Contemporary Resonance

Today, when images are infinitely multiplied and distributed, a seventeenth-century print dealer might seem remote. Yet the portrait feels contemporary because it honors curatorial intelligence—the skill of selecting, contextualizing, and caring for images in a crowded world. Clement de Jonge’s poise resonates with anyone who mediates between art and audience, whether gallerist, editor, or digital archivist. Rembrandt’s insistence on the dignity of that role gives the print a quietly modern grace.

Conclusion

“Portrait of Clement de Jonge” is a tribute to the ecosystem that made Rembrandt’s own art possible. With controlled light, supple line, and a profound respect for the sitter’s vocation, the artist creates an image of professional steadiness and human warmth. The cloak’s monumental folds, the chair’s sober geometry, the gloves poised for handling paper, and the lucid gaze together form a portrait of judgment at rest. It is a likeness of a man and, equally, a portrait of a trade—a reminder that behind every great work on paper stands the eye and care of someone who brings it to the world.