Image source: wikiart.org

Meeting Allan Stein: A Modern Portrait With a Direct Gaze

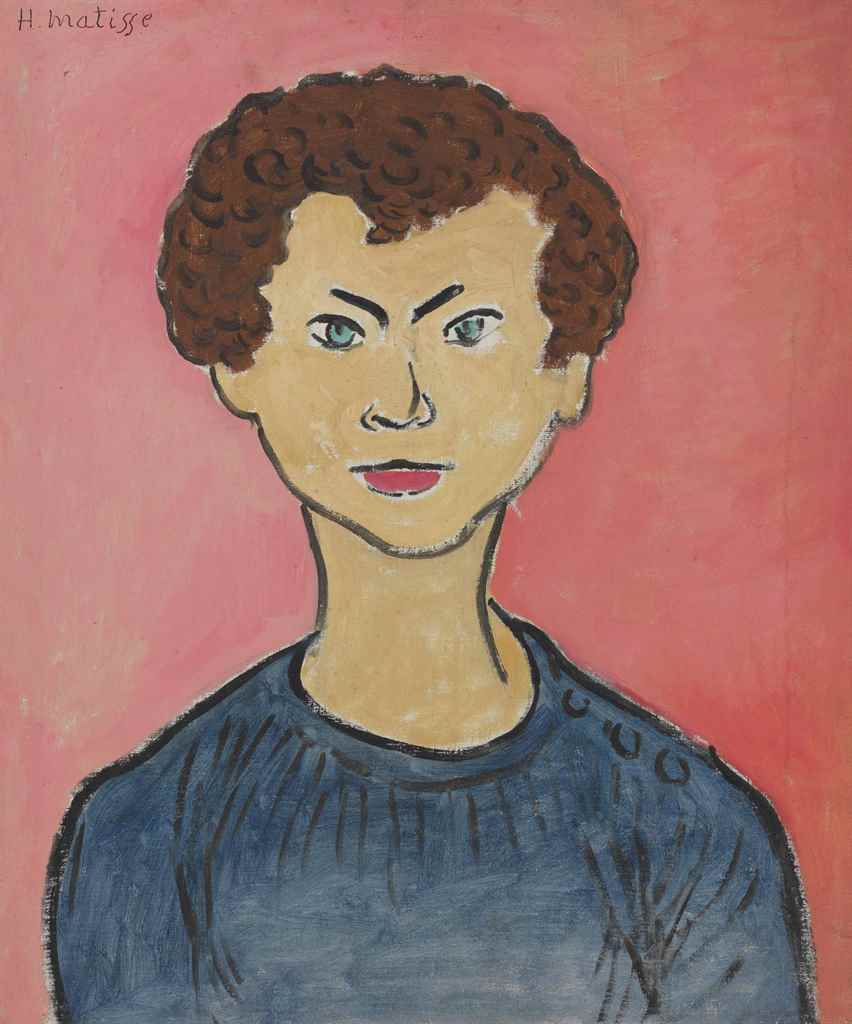

Henri Matisse’s “Portrait of Allan Stein” from 1907 confronts the viewer with a startling economy of means. A young boy appears frontally against a saturated pink ground, his curly hair and sea-glass eyes framed by an assertive black contour. The face is modeled with pared-down tones of ochre, cream, and pale green, while the navy shirt is defined less by shadow than by calligraphic sweeps of line. Nothing here is incidental. The background is a single, pulsing field; the features are simplified to essentials; the whole design relies on the tension between flat color and emphatic outline. In this compact canvas, Matisse distills years of experimentation into an image that feels at once intimate and icon-like, personal and modern.

The Stein Circle and the Intimacy of Patronage

Understanding this portrait begins with the sitter’s identity. Allan Stein was the son of Michael and Sarah Stein and the nephew of Gertrude Stein—collectors and champions of Matisse from the earliest days of Fauvism. The Steins’ Paris apartment became a crucible for the avant-garde, where Matisse’s canvases hung beside Picasso’s and where family members often modeled for artists they supported. Painting Allan was not a commissioned society portrait in the nineteenth-century sense; it was a depiction born of proximity and trust. That closeness helps explain the unguarded, slightly mischievous look, the absence of costume or props, and the compositional frankness. Matisse paints the boy not as allegory or social type, but as a presence he knows—concentrated, alert, and on the threshold of adolescence.

1907: From Fauve Fire to Structural Clarity

The year 1905 had made Matisse notorious for blazing chroma and seemingly anarchic brushwork. By 1907, his color remained audacious, but he was refining the structure that held it. “Portrait of Allan Stein” shows that shift. The coral-pink field is bold, but it is controlled—laid in broadly to keep the surface calm. The shirt’s dark blue is rich, yet organized by repeated arcs and seams that settle the form. Most revealing is Matisse’s use of contour. Heavy, confident outlines carve figure from ground the way a printmaker’s ink bites into paper. This drawing with paint yields a new stability that would support his next decade of interiors and portraits.

Design and Proportion: A Bust-Length Icon

Matisse opts for a bust-length format that echoes devotional images while remaining rooted in the everyday. The head occupies the canvas’s upper third, crowned by a cloud of tight curls that flatten against the pink plane like a dark halo. The shoulders expand to the picture’s edges, giving the boy an almost architectural presence. Triangular relationships quietly stabilize the composition: the V of the neck, the wedge of the jawline, the peaked arch of the brows. These small geometries counter the softness of hair and flesh, keeping the viewer’s attention from drifting. The proportions are neither photographic nor strictly academic; they are tuned to the emotional weight of the gaze.

Color as Character

Color does the psychological heavy lifting. The pink ground is not merely decorative. It sets a warm atmospheric pressure that charges the eyes’ cool green and the shirt’s oceanic blue. Those greens and blues are near-complementary to pink, so they appear to vibrate outward, giving Allan’s gaze a slight phosphorescence. The skin tones are reduced to two or three values—pale ochre, milky cream, and a touch of green along the temple and jaw. That green is not “realistic” but strategic; it helps turn the form and, more importantly, creates a living counter-rhythm within the face, keeping the portrait from settling into an inert mask. The red of the lips is moderated rather than flaming, but in the pink atmosphere it reads decisively, a focal note of speech and individuality.

The Authority of the Outline

Matisse’s black contour is not a boundary in the naturalistic sense; it is a declarative stroke that shapes identity. Around the hair and shirt, it forms a thick crest, separating figure from background like cut paper. Around the features, it thins and tightens, becoming graphic—two arcs for brows, a few tapered lines for the nose, a gentle hinge for the mouth. This shifting weight of line gives the face its mobility. Look long enough and the expression oscillates between impish and serious, in part because line admits micro-variations that depict changing thought rather than a frozen likeness. The outline also refuses the tyranny of light source. Modeling is minimal; the boy is held together by drawing, not cast shadow. The effect is modern and timeless at once.

Brushwork: From Calligraphy to Scumble

Though the portrait looks simple, the paint surface reveals variety. The background’s pink is scumbled thinly, allowing subtle tonal ripples that keep the field from feeling dead. Hair and shirt are handled with a fuller, draggy stroke that lets the bristle marks accumulate like parallel hatchings in ink. The face is smoother, with small merges of tone rather than built-up impasto. This selective handling guides the eye: it rests on the face, skims across the hair’s textured ring, and then lingers on the shirt’s dark waves, which echo ocean or fabric folds without over-describing either.

The Psychology of a Gaze

Allan’s slightly raised eyebrows, the angular bridge of the nose, and the direct but not confrontational eye contact form a portrait of concentration. He appears to meet us, measure us, and remain unflustered. That calm is not passive; it carries the active intelligence of a child used to adult company and conversation, which the Stein salons surely provided. The firm mouth, neither smiling nor tight, avoids sentimentality. Matisse resists dramatics and instead courts a low, constant flame of attention. The result is a portrait that rewards prolonged looking not with a single narrative but with a deepening sense of a mind at work.

Between Primitivism and Classicism

Matisse in 1907 was absorbing lessons from sources then labeled “primitive”—African sculpture, Oceanic carvings, Byzantine icons—alongside his reverence for classical measure. The mask-like simplification of Allan’s features, the black contour, and the planar treatment of the face owe something to those non-Western and medieval models, not as quotation but as structural inspiration. At the same time, the balanced proportions and quiet frontality recall classical busts. This alloy of influences allows Matisse to achieve gravity without heaviness, stylization without caricature.

The Background as Active Space

The pink setting is an active participant, not a neutral void. Because it is continuous, the ground behaves like a field of light rather than a wall. Around the head, it comes forward; around the torso, it recedes, a perceptual play achieved without changing hue drastically. This softly breathing space is what modernists meant by “decorative” in the best sense: an arena where color orchestrates depth and feeling without descriptive furniture. In this roomless room, Allan’s presence becomes all the more pronounced.

Clothing as Shape and Sign

The dark shirt does double duty. It locates the sitter in contemporary life—this is a child, not a mythic figure—but it also performs as a large, stabilizing shape. The shoulder seam and a row of circular accents near the collarbone introduce a small pattern that humanizes the expanse of blue. The shirt’s matte breadth allows the face to bloom by contrast, much as a dark mat sets off a bright print. By resisting detail, Matisse turns clothing into a compositional tool rather than a narrative distraction.

Comparisons Within Matisse’s Portraiture

Set alongside “The Green Line” (1905), where a green stripe divides Madame Matisse’s face and color partitions construct the head, the Allan Stein portrait is a cousin with less drama and more serenity. Put it beside “Marguerite” from 1906, and you see Matisse’s increasing belief in outline as a unifying force. Compared to the almost sculptural roughness of “The Young Sailor” (1906), this canvas softens the facture and brings the focus inward. The throughline is Matisse’s insistence that likeness can be carried by rhythm and color just as faithfully as by an elaborated anatomy.

A Portrait of Modern Childhood

Turn-of-the-century portraits of children often tip toward either idyllic sweetness or coded social ambition. Matisse steers between those poles. Allan is neither cherub nor miniature adult. The portrait respects his emerging autonomy. The directness of the eyes and the graphic crispness carry a child’s clarity—no elaborate interior, no parent hovering, no instructive prop like a book or toy. The painting thereby feels modern not only in style but in its view of childhood as a distinct, self-possessed state.

The Ethics of Simplification

Simplification is not the absence of care; it is the result of it. Matisse reduces the number of tones and the complexity of shapes to what the image truly needs. Each decision is ethical as well as aesthetic, a disciplined refusal of ornament that does not serve the subject. The proof is in how little it would take to unbalance the portrait. Add a patterned background and the gaze would weaken; introduce heroic modeling and the face would stiffen. By holding the line—literally and figuratively—Matisse preserves the boy’s quick vitality.

Time, Memory, and the Portrait’s Afterlife

Because this image was painted within a private circle, it carries a layer of familial time. Viewers who know the history of the Steins may read into the portrait the birth of a new aesthetic supported by collectors willing to live with its shocks. But even without that context, the picture functions broadly as an emblem of how early modern art made room for ordinary life. It honors a singular child while offering a template for seeing anyone freshly: as a constellation of shapes and colors that, rightly arranged, speaks of personality more powerfully than detail.

How to Look at “Portrait of Allan Stein”

Begin at the eyes and let the black lines lead you. Notice the slight difference in the arcs of the brows, the way the inner corners of the eyes are anchored and the outer corners lighten, keeping the gaze open. Drift down the nose’s falcon-like contour and settle on the mouth’s clean hinge. Step back and allow the face to float forward against the pink field; then step close to read the variety of paint on the shirt’s blue. Oscillating between near and far reveals how Matisse designed the work to snap into focus at multiple distances, a hallmark of his best portraits.

Legacy and Relevance

“Portrait of Allan Stein” demonstrates why Matisse remains a touchstone for painters of the figure. It shows that radical color and clear drawing need not be opposites, that tenderness and modernity can coexist. In classrooms and studios, artists still analyze the way this portrait balances simplification with vibrancy. For general viewers, the canvas offers something equally durable: the reminder that seeing is an act of attention. The picture pays Allan the compliment of looking at him carefully enough to know what to leave out.

Conclusion: An Icon of Affection and Clarity

In a handful of decisive moves—pink ground, blue shirt, black contour, lucid features—Matisse makes a portrait that feels inevitable. It is not flashy, yet it shines; it is not descriptive in the old sense, yet we feel we know the sitter. “Portrait of Allan Stein” reveres the act of looking as a form of attachment and makes of a child’s visage a small, enduring icon of modern painting.