Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

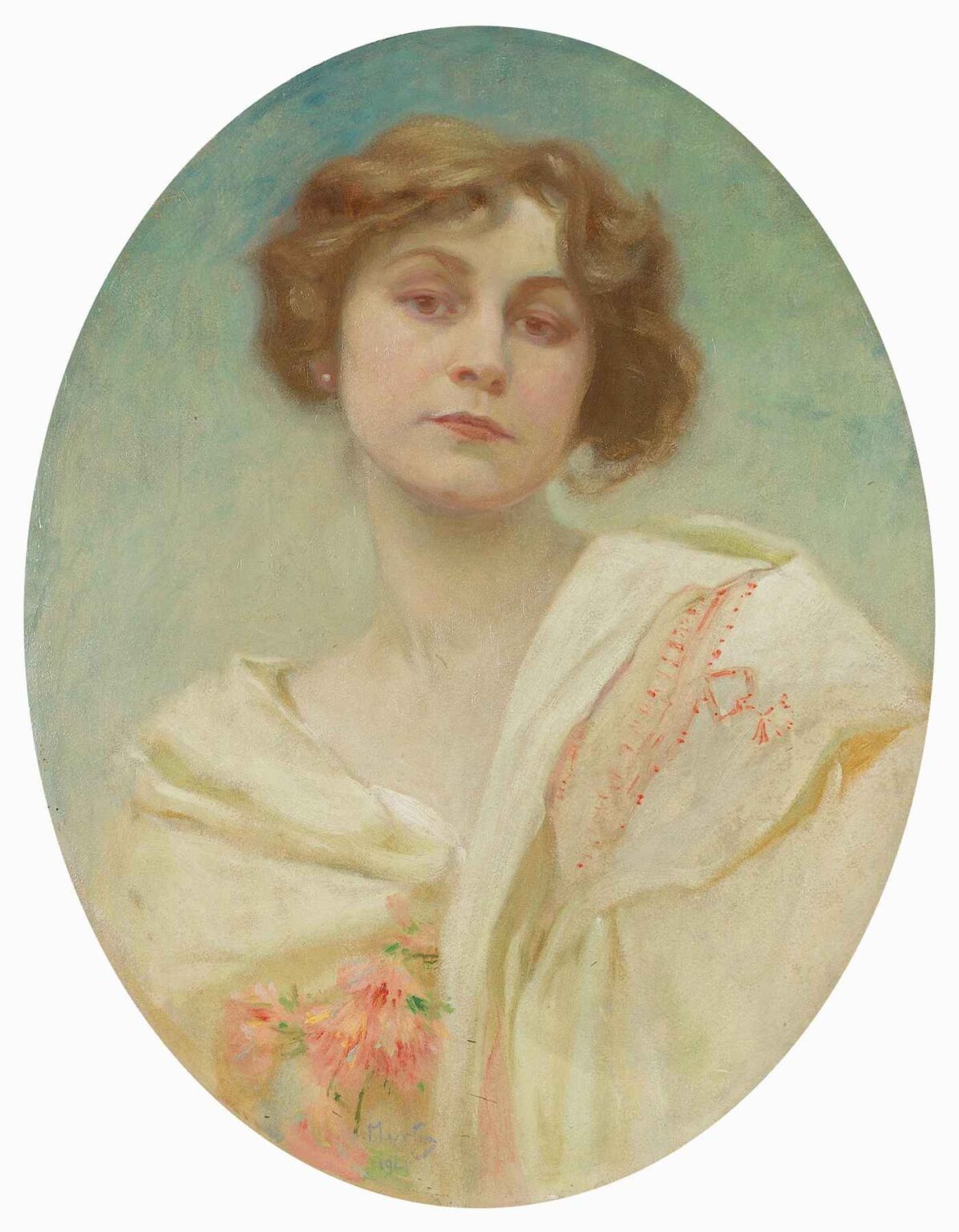

Alphonse Mucha’s “Portrait of a Young Woman in Folk Costume” (1921) stands as a masterful example of his later portraiture, in which his Art Nouveau roots converge with a deeply personal engagement with Slavic folk traditions. Executed in pastel and oil on board within an oval format, the painting captures a moment of quiet introspection and cultural affirmation. The young woman’s embroidered shawl and floral adornments signal her local heritage, while Mucha’s refined handling of line and color lends her an almost iconic presence. Moving beyond commercial poster art, Mucha here creates a work that bridges the decorative and the intimate, the collective and the individual—offering a vision of modern womanhood grounded in historical roots.

Historical Context and National Revival

The early 1920s were a period of intense cultural reevaluation for Mucha, coinciding with the recent founding of Czechoslovakia in 1918. Having campaigned for Slavic unity and Czech independence, Mucha turned increasingly to subjects that celebrated national character. Folk costumes—once regarded as the attire of rural peasants—became emblems of a proud national identity, and Mucha embraced their vivid embroidery and time-honored patterns as worthy subjects for fine art. “Portrait of a Young Woman in Folk Costume” thus emerges against a backdrop of post-war renewal, embodying the optimism and cultural pride of a nascent republic eager to define itself through both tradition and modernity.

Commission and Patronage

While much of Mucha’s fame derived from theatrical posters and magazine illustrations, his later career included private portrait commissions aimed at collectors and cultural institutions. “Portrait of a Young Woman in Folk Costume” likely originated from a request by a patron interested in both the sitter’s likeness and the promotion of Slavic folk heritage. Mucha’s social standing and reputation allowed him access to models and patrons across Central Europe. By 1921, he enjoyed the support of national art societies and received state commissions for his monumental “Slav Epic.” Portraits like this one offered a more intimate counterpoint to grand history paintings, focusing instead on the everyday dignity of individual sitters within their cultural milieu.

Oval Format and Compositional Balance

Mucha elects an oval composition—a device he favored for his decorative panels and medallions—to frame his subject in a manner that recalls classical portrait miniatures and ecclesiastical icons. The oval shape softens corners, directing the viewer’s gaze toward the sitter’s face and embroidered shawl. Positioned slightly off-center, the young woman’s figure balances the composition: her head tilts gently upward, while the shawl’s draped folds sweep diagonally across the lower half, creating a dynamic interplay of lines. The generous margin around the oval allows the pastel strokes to breathe, enhancing the sense of intimacy and suspension.

The Sitter’s Expression and Psychological Depth

Central to the painting’s power is the young woman’s nuanced expression. Rather than a direct gaze, she looks downward and to the viewer’s left, eyes partially hooded in contemplative reserve. Her lips, closed yet softly defined, suggest both reticence and calm dignity. Mucha’s pastel technique—layering faint touches of rose and ochre—renders her skin with an otherworldly translucence. The psychological subtlety marks a departure from his earlier theatrical heroines, revealing an interest in interiority over dramatic gesture. Here, the portrait becomes a window into individual emotion, set against the broader canvas of national tradition.

Pastel and Oil Technique: Medium Mastery

Mucha’s fusion of pastel and oil paint demonstrates his technical versatility. He likely began with a thin underlayer of oil or tempera to establish warm undertones, then applied pastel sticks for the face, hair, and shawl highlights. The pastel’s velvety finish allows for delicate color modulation, while the oil underpainting ensures durability and depth. Mucha’s patented layering—softly blending pastels with minimal fixative—preserves luminosity and prevents cracking. The embroidery’s coral-red stitchwork, executed with knife-edge pastel, retains sharpness against the gauzy shawl folds. This hybrid approach exemplifies Mucha’s commitment to marrying painterly subtlety with decorative precision.

Costume and Textile Detailing

Folk costume occupies a place of honor in this portrait. The cream-colored shawl, draped over the sitter’s shoulders, features coral-red embroidered motifs—geometric stitches and stylized flowers—typical of Moravian and Slovak linen work. Mucha records these stitches with surprising specificity; each group of cross-stitches and diagonal bars appears intentionally placed, reflecting ethnographic accuracy. Beneath the shawl, a cluster of soft pink blossoms emerges—possibly real flowers tucked into her bodice—linking her attire to the natural world. These textile details serve both as cultural signifiers and as decorative flourishes, integrating folk art into the vocabulary of high art.

Symbolism of Color and Embroidery

The color choices in “Portrait of a Young Woman in Folk Costume” carry symbolic resonance. The coral-red embroidery—vibrant against the ivory shawl—invokes vitality, protective symbolism, and fertility traditions associated with rural Slavic garb. Pink blossoms connote youth, beauty, and the renewal of spring, aligning with folk customs of flower-wreathed maidens. The background’s cool green-blue gradient provides a complementary contrast, framing the warm hues without competing for attention. Through this palette, Mucha conveys both the sitter’s individual warmth and the wider cultural symbolism embedded in her attire.

Hair, Jewelry, and Feminine Identity

The sitter’s hairstyle—soft brown curls cut just above the shoulders—signals a modern, liberated femininity that coexists with traditional costume. Small pearl earrings glimmer at her lobes, introducing a note of refined urban fashion. This juxtaposition of rural shawl and contemporary haircut suggests the sitter’s dual identity: rooted in folk heritage yet participating in the modern world. Mucha’s nuanced rendering of hair—using tinted pastel strokes to capture individual strands—reinforces this blend of realism and adornment. The pearls, touched with pure white pastel, echo his use of highlight in earlier portraits of theatrical stars, linking methods across decades.

Background Treatment and Atmosphere

Rather than depicting a detailed setting, Mucha opts for a softly graded background of greenish-blue pastel washes. The sky-like ambiance dissolves behind the sitter, isolating her figure and preventing external distractions. This neutral backdrop also evokes the atmospheric haze of sunrise or a spring meadow, subtly connecting to the floral motifs on her shawl. The lack of hard edges underscores the portrait’s focus on mood and personality rather than location. By keeping the background unobtrusive, Mucha intensifies the viewer’s engagement with the sitter’s expression and costume.

Integration of Decoration and Realism

Throughout his career, Mucha sought to blur boundaries between decorative pattern and figural representation. In “Portrait of a Young Woman in Folk Costume,” this integration reaches a mature expression: the shawl’s embroidery, the blossoms, and even the sitter’s hair filaments become part of the overall ornamentation, while her psychologically acute likeness grounds the work in realism. The two modes—decorative and naturalistic—remain in balance, each enhancing the other. This synthesis exemplifies the Art Nouveau ideal that art should permeate every aspect of life, from grand murals to intimate personal portraits.

Technical Collaboration and Studio Practices

Executing a pastel-and-oil portrait of this sophistication required collaboration among Mucha’s studio assistants and skilled pastel technicians. Preliminary charcoal or pencil sketches would map the composition, followed by underpainting in oil. Pastel application demanded a smooth board surface; Mucha and his assistants likely prepared the support with a thin gesso ground. Layering pastel posed challenges—each layer needed gentle fixing to prevent smudging while preserving the medium’s matte brilliance. Mucha then added final highlights and retouched key features. This rigorous process underscores his dedication to technical excellence, ensuring that the portrait’s decorative flourishes did not compromise its durability.

Reception and Place in Mucha’s Body of Work

Although overshadowed in later decades by Mucha’s “Slav Epic” cycle and his celebrated Belle Époque posters, “Portrait of a Young Woman in Folk Costume” has garnered renewed appreciation as a bridge between his early decorative achievements and his later nationalistic endeavors. Exhibited in solo shows and reproduced in art journals of the 1920s, the painting appealed to intellectuals and cultural organizations invested in Slavic heritage. Today, art historians view it as a pivotal work: one that marries Mucha’s signature decorative style with an intimate, empathetic portrait sensibility, marking his evolution as both a public artist and a sensitive chronicler of individual identity.

Conservation and Modern Display

Original pastel works require meticulous conservation: pastel pigments are inherently friable, and boards can become acidic over time. Museums housing “Portrait of a Young Woman in Folk Costume” employ acid-free matting, UV-protective glazing, and controlled humidity to prevent pigment fading and substrate degradation. Digital archiving has further democratized access, allowing scholars to study the painting’s subtle pastel textures and stitch-by-stitch embroidery details without risking damage to the original. The portrait’s continued exhibition in major European galleries underscores its enduring resonance as both a work of art and a document of cultural history.

Influence on Later Generations

Mucha’s late portraiture, epitomized by “Portrait of a Young Woman in Folk Costume,” influenced subsequent generations of figurative painters and illustrators interested in blending ethnographic detail with decorative innovation. In the 1930s and ’40s, Eastern European artists revisited folk motifs within modernist frameworks, citing Mucha’s approach to ornament as a guiding example. Even beyond Slavic circles, the painting inspired pastel portraitists seeking to reconcile realism with stylized pattern. Its legacy endures in contemporary design, where folkloric embroidery often resurfaces in fashion and illustration, echoing Mucha’s pioneering fusion of costume study and fine art.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Portrait of a Young Woman in Folk Costume” remains a richly layered testament to his lifelong devotion to beauty, cultural identity, and technical mastery. Through the harmonious interplay of pastel delicacy, oil underpainting, and intricate embroidery details, Mucha elevates a simple folk shawl into a universal emblem of national pride and feminine grace. The sitter’s serene expression and the painting’s oval format evoke both classical portraiture and decorative medallion traditions, while the soft background places her in a timeless, dreamlike space. Over a century after its creation, the portrait continues to captivate viewers, affirming Mucha’s genius in marrying individual psychology with collective heritage—and demonstrating that the most intimate of studies can also speak to the grandest of cultural narratives.