Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

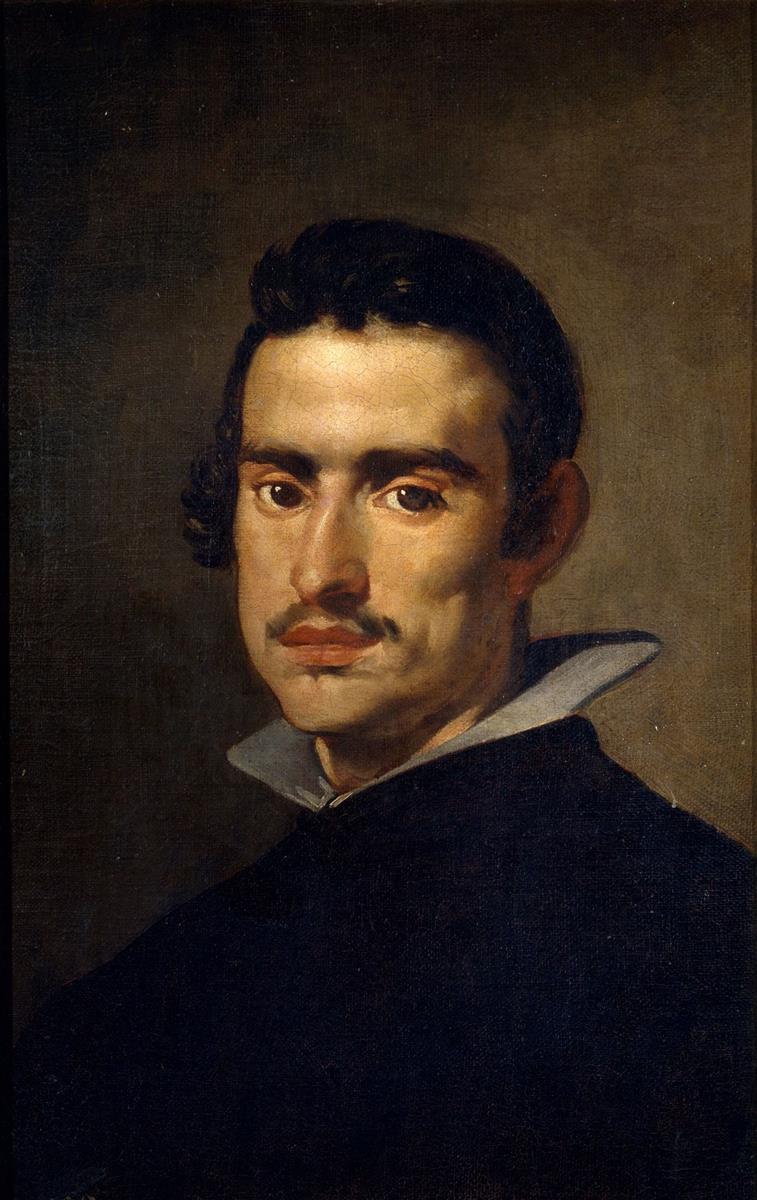

Diego Velazquez’s “Portrait of a Young Man” (1623) is a taut, intimate study of presence at the threshold of the artist’s Madrid career. The canvas presents a head-and-shoulders likeness in three-quarter view, set against a warm, unarticulated ground. A crisp, upturned collar frames the jaw; the garment below sinks into disciplined darkness; the face is modeled by a raking light that clarifies bone and flesh without theatrical exaggeration. Nothing distracts from the encounter. Velazquez uses the most economical means—tone, edge, and a handful of colors—to show how attention itself can become a form of characterization. The result is not merely a likeness but a distilled psychology, an image that feels as modern as it is Baroque.

Historical Moment

Painted in 1623, the portrait belongs to the hinge between Velazquez’s Sevillian bodegón years and his ascendancy in Madrid. The young painter had already made a case for himself with austere scenes of taverns and kitchens and with spare, penetrating portraits of intellectuals and clerics. Madrid required different virtues: poise, courtly tact, and an ability to confer authority without ornament. This “Portrait of a Young Man” shows Velazquez calibrating his Sevillian realism to the capital’s expectations. The austerity remains, but it has been refined. The palette narrows, the background quiets, and the psychology intensifies. The painting announces a painter prepared to portray power while remaining faithful to the ethics of truth that shaped him.

Subject and Identity

The sitter’s identity is uncertain, and Velazquez allows the picture to stand independent of biography. He refuses emblematic props—no book, glove, or scroll—so that the face must carry meaning unaided. The man is young, alert, and self-possessed. The modest mustache and carefully brushed hair support the impression of urbanity; the neat collar speaks of order; the turned head implies readiness. Because the portrait withholds a name, it becomes a study of type and character: a Madrid gentleman at the opening of adulthood, caught between ambition and composure.

Composition and Pictorial Architecture

Velazquez builds the composition from a few stable forms. The mass of the dark garment establishes a wedge that pushes the head into space. The upturned collar creates a luminous triangle beneath the jaw, separating flesh from cloth with a single decisive contour. The head sits just off-center, turned to the viewer’s left; this twist sets up countervailing diagonals—the line of the nose and brow, the slope of the cheek, the delicate fall from temple to ear—that animate the otherwise tranquil arrangement. Background space remains a softly modulated brown, neither wall nor void, which grants the head air without distracting detail. Every compositional decision funnels attention toward the eyes.

Light and Chiaroscuro

Light enters from above left, laving the forehead, sliding down the bridge of the nose, and striking cheek and lip before easing into the half-tones that cradle the far jaw. This is not the theatrical tenebrism of Roman Caravaggism; it is a disciplined, clarifying light that reports what is necessary to believe the head is present. Edges are sharpened where the light demands it—the gleam at the eyelid, the bright seam of the collar—and softened where form turns softly away—the cheek’s descent, the shadow under the chin. The effect is sculptural without hardness. The sitter seems to occupy breathable air, not a cutout stage.

Color and Atmosphere

The palette is a masterclass in restraint. Flesh modulates through warm ochers, peaches, and olive half-tones, cooled just enough around the eyes to suggest thin skin. The collar introduces a steely gray-white that borrows reflections from the flesh and background, keeping it a part of the same atmosphere rather than a pasted emblem. The garment’s black is alive with muted browns and violets, claiming mass rather than mere darkness. The ground hovers between raw umber and subdued brown, calibrated so the head neither floats nor sinks but sits in space. This limited color world creates emotional unity—calm, serious, humane.

The Collar as Pictorial and Moral Device

The upturned collar is more than costume. It is a structural and rhetorical instrument. Structurally it frames the head, catching light that rebounds into the lower face, and sets a crisp edge that articulates turn and posture. Rhetorically it declares order and readiness, the starched discipline of a man who belongs to a world of rules. Velazquez paints it with deliberately varied touch: a knife-sharp outer edge, a softened inner fold, and a few cool planes that indicate thickness. The collar’s restraint is a counterpoint to the softness of skin, and in that contrast the portrait finds its poise.

Physiognomy and Specificity

The face avoids the generic at every turn. The eyebrows are slightly asymmetrical; the nose has its own profile; the lips carry a subtle mixture of firmness and youth. The ear is not a type but this ear, with its individual whorls and angle. A faint mustache shadow softens the sternness of the mouth, and a single lock of hair near the temple breaks the otherwise careful grooming, a tiny breach that humanizes the presentation. Velazquez records these particulars without fuss, allowing them to build character naturally, as details do in conversation.

The Gaze and Psychological Charge

The eyes are frontal without aggression. They meet ours with a steady curiosity that suggests intelligence and self-command rather than challenge. The upper lids rest on the orbs, tempering youthful brightness with gravity. The mouth, closed and slightly compressed, implies a habit of measured speech. Together, gaze and mouth stage the portrait’s drama: a young man conscious of being seen, tested by attention, and proving equal to it. Velazquez never forces expression; instead he lets micro-gestures accrue to a complex, believable state of mind.

Texture, Edge, and Material Truth

Part of the picture’s authority comes from how convincingly it differentiates materials with minimal means. Skin is built with fused strokes that preserve translucency; the hair is not counted strand by strand but suggested with directional marks that follow growth and light. The collar bears the dry sheen of starched linen, distinct from the soft reflectivity of skin. The black garment reads as heavy cloth because of tiny variations of value and temperature, not because of decorative rendering. Everywhere Velazquez subordinates description to optical truth, letting each surface speak in its own accent.

Space, Silence, and Proximity

The portrait is intimate. There is no architectural distance, no curtain, no table between us and the sitter. The background’s low murmur functions like acoustic padding, heightening the sense of a quiet room. Because the head fills the frame generously, we register small phenomena with unusual clarity: the moist catchlight in the eye, the faint redness at the lip, the cool reflection along the jaw’s shadow edge. The silence of the setting is therefore an active device; it teaches the viewer to look with the same calm intensity the painter practiced.

Technique and the Discipline of Brushwork

Velazquez’s touch is economical and exact. He models the forehead with long, gently fused strokes that honor curvature without slipping into polish. The nose is described by value shifts rather than outline, its contour asserted only where the lit plane meets the shadow. The mouth is a marvel of restraint: two planes and a narrow highlight on the lower lip suffice to convince. The collar’s edge is pulled with a single, confident stroke and then weighted with small tonal steps to express thickness. The ground is not a monotone; it is a living surface of varied brush that keeps the atmosphere breathable. The technique is invisible until one searches for it, and then it reads like a series of lucid decisions.

Dialogue with Sevillian Bodegones

Though a portrait, the canvas breathes the same ethic as Velazquez’s kitchen scenes. In the bodegón, a jug or knife is dignified by exact seeing; here, a human face is dignified in precisely the same way. The painter’s refusal to flatter, his love of honest blacks and whites, and his belief that light tells truth—all are the bodegón’s legacy. The difference lies in the stakes. A still life persuades by tactile conviction; a portrait must carry psychological truth as well. Velazquez brings the still life’s integrity to the face, and the result is a likeness that feels both materially and morally convincing.

Social Signals and Class

Costume and grooming place the sitter within the urban middle or upper-middle ranks: a fine but unostentatious garment, a starched collar, hair carefully managed, a mustache in fashion. Yet the portrait declines to become a display of status. Social cues are present, but they are subordinated to character. Velazquez’s approach anticipates the balance he would later achieve in court portraiture, where rank is undeniable yet personality remains sovereign. Even here, in modest scale, the painter experiments with how to give a person authority without props.

Time and Chosen Instant

The head’s slight twist implies movement arrested just after the turn. We feel the preceding second when the sitter faced away and the coming second when he might address us with speech. By freezing this hinge, Velazquez thickens time. The portrait becomes not a static mask but a living pause, a breath held in the moment of meeting. That temporal sensation—so often the secret of Velazquez’s vitality—gives this small image its large presence.

Comparisons within the Early Madrid Period

Alongside the “Portrait of Don Luis de Góngora y Argote” and the “Portrait of a Cleric,” this painting completes a triptych of early Madrid likenesses that establish Velazquez’s method. All three share luminous blacks, unornamented backgrounds, and concentrated gazes; each adjusts the register to suit the sitter. Where Góngora’s features compact intellectual severity, the cleric’s bear pastoral gravity, and the young man’s convey potential energy held in check. The painter’s voice is consistent; his tuning is precise.

The Rhetoric of Black

Spanish portraiture made black a language of seriousness, and Velazquez speaks it fluently. Painting black well is notoriously difficult: it must hold light and describe weight without dissolving into flatness. Here the garment’s deep tone is broken by barely perceptible variations—warmer near the collar, cooler toward the shoulder—that state volume and fabric. Against this field the face becomes luminous, and the collar’s clean line achieves maximum rhetorical force. The choice of black is therefore not only historical but pictorial; it gives the portrait its gravity and its clarity.

The Viewer’s Experience

Encountering the painting at close range, the viewer experiences a progressive discovery. From across the room, the head reads as a simple, compelling form illuminated against brown. Step closer and the eyes begin to govern the exchange; closer still and the delicate sutures of brushwork resolve into living phenomena. One notices how a tiny highlight on the lower eyelid moistens the gaze, how the warm ground warms the shadowed jaw, how the collar’s edge slightly frays into the air to avoid cutout stiffness. The painting rewards slowness. It invites the kind of looking that transforms acquaintance into knowledge.

Anticipations of the Court Painter

Within months Velazquez would paint the young Philip IV and take his place at court. The virtues on display here would make that appointment inevitable: command of likeness without flattery, mastery of subdued color, the ability to confer presence through light alone, and a humane attention that never reduces a person to role. This “Portrait of a Young Man” is thus both a finished work and a prospectus. It proves that the painter can make a face bear the weight of dignity without resorting to the pomp of accessories.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

The portrait endures because it models a way of seeing that remains persuasive: pared-down means, maximum presence, ethics before ornament. In an age that often confuses display with depth, Velazquez offers a counterexample. He shows that a limited palette and a simple composition can carry immense psychological charge when handled with intelligence and care. The painting’s relevance lies in its trust in the face as a sufficient sign of character, and in the painter’s belief that attention—patient, accurate, unsentimental—is the ultimate instrument of art.

Conclusion

“Portrait of a Young Man” demonstrates how Velazquez could summon a living person with almost nothing: a head turning into light, a collar’s crisp chord, a field of breathable brown, and the rigor of a gaze that meets our own. The painting is quiet, but its quiet carries authority. It dignifies youth without idealizing it, registers ambition without boast, and proclaims—without a single flourish—the values that would guide one of the greatest portraitists in Western art. Looking into its measured light, we meet not just a sitter but a standard: truth rendered with restraint, and restraint made radiant.