Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

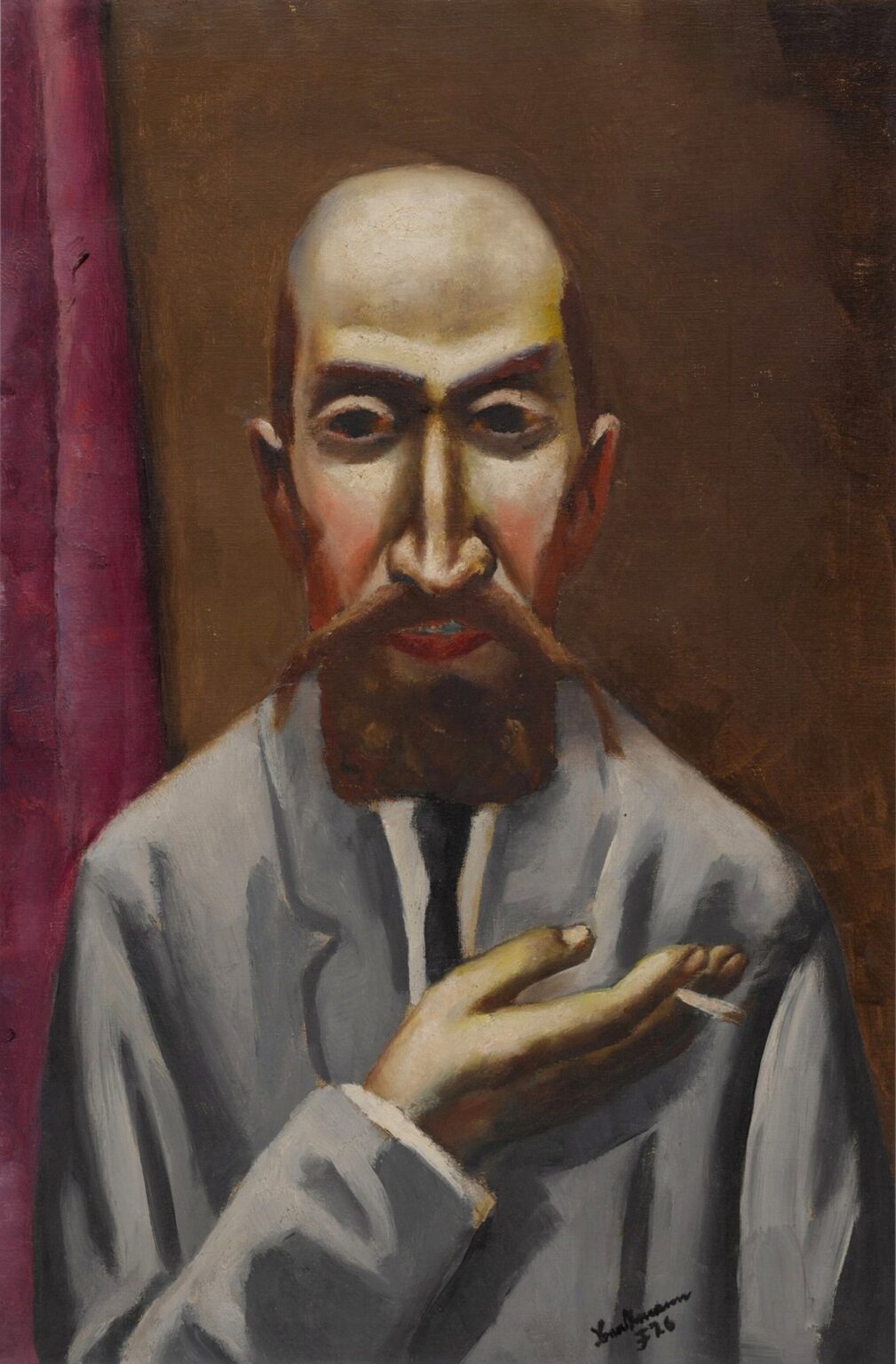

Max Beckmann’s Portrait of a Turk (1926) stands as a striking testament to the artist’s postwar maturity, blending raw psychological insight with a disciplined formal structure. Executed in oil on canvas, the painting depicts a single figure—identified by both the viewer and archival records as “the Turk”—rendered with arresting precision and unsettling intensity. Rather than recording a straightforward likeness, Beckmann uses distortions of color, shape, and gesture to probe deeper questions of identity, cultural encounter, and the burdens of the modern world. Over the course of this analysis, we will explore the painting’s historical context, Beckmann’s evolving style, its compositional strategies, chromatic innovations, and symbolic resonances, ultimately revealing how Portrait of a Turk remains a powerful meditation on the human condition in the interwar era.

Historical Context

1926 marked a period of uneasy calm in Germany’s Weimar Republic. The hyperinflation crisis of the early 1920s had subsided, and the Dawes Plan had stabilized the economy, yet political tensions lingered and the memory of World War I’s devastation remained fresh. Beckmann, himself a veteran of the conflict, returned from military service with a heightened awareness of society’s fragility. During the 1920s, he served as a professor at the Städelschule in Frankfurt, where he engaged with students, intellectuals, and visiting artists. It was in this cosmopolitan milieu that he encountered figures from diverse backgrounds, including immigrants and itinerant workers—among them the man he painted as “the Turk.” This portrait, therefore, emerges not only from Beckmann’s personal quest to understand the fractured postwar psyche, but also from his direct engagement with cultural difference in an era of both creative ferment and xenophobic anxiety.

Beckmann’s Artistic Evolution

Prior to World War I, Beckmann’s work displayed the lyrical ornamentation of Jugendstil and the vivid color palette of early Expressionism. However, the war catalyzed a shift toward a more somber, rigorous style. By the mid-1920s, Beckmann had synthesized the emotional force of Expressionism with a newfound structural discipline—often referred to as “Neue Sachlichkeit” (New Objectivity), although his allegiance was to neither camp exclusively. In Portrait of a Turk, one sees the culmination of this evolution: the tight, angular modeling of form recalls his earlier etchings, while the stark spatial arrangement and restrained—but pointed—use of color reflect his mature painterly vocabulary. The painting thus occupies a liminal space between representation and abstraction, between individual psychology and cultural archetype.

Formal Analysis: Composition and Space

Beckmann composes Portrait of a Turk around a centrally placed figure whose imposing presence fills the vertical plane of the canvas. The man stands in quasi-frontal pose, his shoulders slightly turned, creating a subtle diagonal that animates the composition. Behind him, a neutral brown backdrop punctuated by a narrow strip of crimson drapery on the left recalls theatrical staging, suggesting both concealment and revelation. The verticality of the curtain contrasts with the horizontal thrust of the figure’s outstretched arm—presented with exaggerated foreshortening—drawing the viewer’s eye to the large hand that holds a cigarette or small object. The interplay of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal lines structures the canvas into interlocking planes, reinforcing the figure’s solidity while hinting at underlying tensions.

Color and Light

The color scheme of Portrait of a Turk is deliberately restrained yet charged with emotional undercurrents. The dominant earth tones—browns, ochres, and muted grays—establish a somber atmosphere, evoking walls darkened by time and memory. Against this backdrop, Beckmann introduces accents of crimson in the drapery and subtle washes of rose in the sitter’s cheeks, signalling both vitality and inner turmoil. The subject’s pale, bald forehead and sharply modeled nose catch light in glints of cool white, creating strong chiaroscuro that sculpts the face with a sense of almost sculptural mass. Shadows deepen around the eyes, mouth, and beard, lending the visage an aura of introspective intensity. Light in this portrait is neither diffused nor gentle; it strikes with precision to reveal contours, as if interrogating the sitter’s very essence.

The Figure and Gesture

Beckmann’s Turk is defined not only by physiognomy but also by gesture. The man’s elongated hand emerges boldly into the foreground, palm up and fingers slightly curled—a gesture that could signify offering, questioning, or defiance. The slender cigarette held between two fingers imbues this gesture with additional ambiguity: is he seeking a moment of vicarious calm, or does the cigarette serve as a prop in a larger performance of identity? His other hand, cropped at the wrist, suggests that Beckmann deliberately excluded traditional markers of social status—such as ornate rings or watch chains—in favor of a pared-down, almost monastic presentation. This shift of focus from clothing to hand accentuates the human touch, the physical presence, and the existential query inherent in the portrait.

Iconography and Symbolism

While Portrait of a Turk eschews overt narrative details, several elements resonate symbolically. The title itself raises questions of cultural encounter and exoticism: in the German imagination of the 1920s, the figure of “the Turk” carried multiple connotations—from Ottoman legacy to wandering peddler—imbued with both fascination and prejudice. Beckmann’s portrayal refuses stereotypical tropes; instead, he grants his sitter dignity and psychological depth. The vertical crimson drape recalls both Eastern textiles and the ceremonial gowns of Western portraiture, bridging cultural divides. The cigarette may symbolize modernity’s vices or a cross-cultural exchange of leisure habits. Even the sitter’s beard, trimmed to a pointed shape, evokes both religious allusion and personal idiosyncrasy. By layering these subtle references, Beckmann transforms a portrait into an allegory of liminality, negotiating between self and other, tradition and modernity.

Psychological Depth and Inner Life

Central to Beckmann’s approach is the conviction that a portrait must reveal the subject’s inner world. In Portrait of a Turk, the sitter’s eyes—narrowed, almost half‑closed—carry an inscrutable expression: neither openly inviting nor wholly withdrawn. His gaze seems to peer into a distant realm, reflecting memories or premonitions beyond the canvas. The tension between the rigid jaw and the soft droop of the eyelids suggests a psychology buffeted by resilience and weariness. Beckmann’s thick brushstrokes capture the texture of skin as well as the mapped lines of lived experience: furrowed brow, tucked moustache, pointed beard. In this way, the painting becomes a record of a life shaped by dislocation, work, and cultural transition, rather than a static icon commemorating mere appearance.

Beckmann’s Brushwork and Surface

Beckmann applies oil paint with a combination of confident, linear strokes and broader, impasto passages. The jacket of the sitter is rendered in stiff grays with visible directional brushwork that emphasizes the fabric’s weight and folds. The face, by contrast, benefits from layered glazes that soften transitions between highlight and shadow, imparting a tactile warmth. In certain areas—such as the drapery and the hand—Beckmann allows the weave of the canvas to show through thin layers of pigment, creating a subtle dialogue between paint and support. This varied treatment of surface underscores his belief in paint as both vehicle of representation and material presence, mirroring the sitter’s own corporeal reality.

Cultural Encounter and Otherness

Beckmann’s decision to title the work Portrait of a Turk foregrounds the sitter’s cultural identity in a way that demands consideration. In post‑Ottoman Europe, the figure of the Turk could symbolize both historical enemy and exotic stranger. Yet Beckmann was no propagator of caricature; he treats his subject with respect and empathy. The portrait avoids Orientalist clichés—no turbans, no harem‑style accessories—instead presenting the man in Western attire, his cultural difference communicated through title rather than costume. This nuanced approach suggests Beckmann’s engagement with the complexities of migration and multicultural interaction in interwar Germany, offering a vision of shared humanity amid political uncertainty.

Position Within Beckmann’s Oeuvre

Portrait of a Turk occupies a unique niche in Beckmann’s extensive catalogue of portraiture. While he frequently painted acquaintances, friends, and members of the artistic milieu, this work stands out for its explicit reference to cultural alterity. It foreshadows later portraits in which Beckmann would grapple with themes of exile, displacement, and the search for identity outside national frameworks—particularly after his emigration during the rise of National Socialism. At the same time, it retains the formal clarity and psychological acuity that define his interwar period. As such, the painting bridges the intimate portraiture of the 1920s and the more overtly allegorical compositions of his later exile works.

Reception and Legacy

During Beckmann’s lifetime, Portrait of a Turk attracted both admiration and consternation. Conservative critics bristled at its unsettling frankness, while avant‑garde circles praised its honest engagement with psychological and cultural complexity. The painting’s reputation grew in the post‑World War II era as scholars recognized Beckmann’s forward‑looking portrayal of multicultural experience. Today, Portrait of a Turk is regarded as a pioneering work that prefigured later explorations of diaspora and identity in twentieth‑century art. Its combination of formal rigor, emotional depth, and cultural nuance continues to inspire contemporary artists grappling with questions of otherness and belonging.

Conclusion

Max Beckmann’s Portrait of a Turk (1926) transcends the conventions of conventional portraiture to become a profound exploration of identity at the crossroads of cultures. Through its disciplined composition, nuanced color palette, and expressive brushwork, the painting conveys both the sitter’s individual psyche and the broader tensions of the Weimar era. Beckmann’s refusal to succumb to stereotype and his commitment to psychological authenticity render this portrait a timeless testament to human complexity. In Portrait of a Turk, one finds not only the face of a single man but a reflection of an age marked by upheaval, encounter, and the enduring search for self.