Image source: wikiart.org

Overview: A Sunlit Square Turned into a Theater of Mediterranean Light

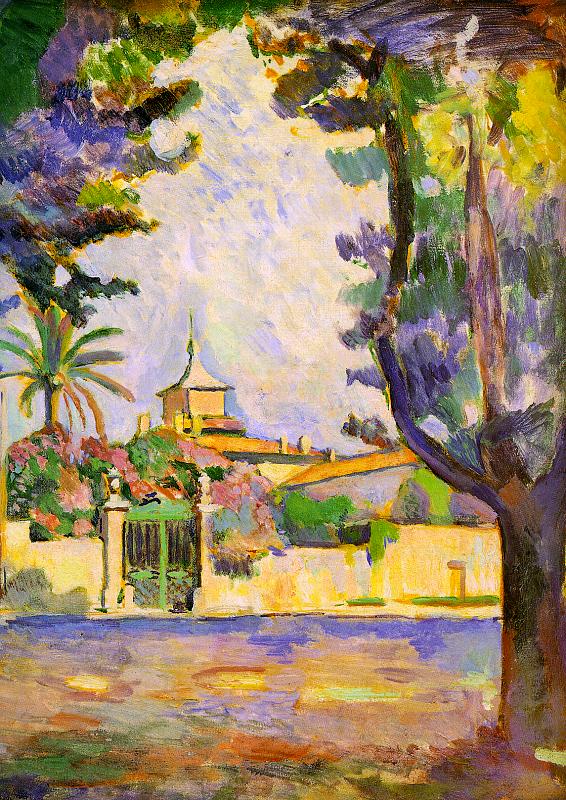

Painted in 1904, “Place des Lices, St. Tropez” captures one of the most emblematic plazas in the south of France at the precise moment when Henri Matisse was pivoting from Neo-Impressionist method toward the liberated chroma of Fauvism. Rather than delivering a topographical record, the canvas offers an orchestration of color relationships: a pale sun-struck wall and green gate at center; a pagoda-capped tower beyond; palm and umbrella pines framing the scene; and, across the foreground, a cool violet band of shade that functions like a threshold the viewer is about to cross. The subject is not simply a square but the sensation of Mediterranean light as it floods stone, foliage, and air.

Historical Context: Between Optics and Emotion

Matisse arrived in St. Tropez in 1904 at the invitation of Paul Signac, the key advocate of Divisionism in France. He had studied color theory and optical mixture with rigor, absorbing the lessons of Chevreul and Rood. Yet the southern climate coaxed him away from strict dotting and carefully schematized color chords. The painting belongs to this hinge moment. You can still feel the discipline of Neo-Impressionism in the broken touches that scintillate across the sky and the street; at the same time, the marks become broader, more responsive to forms and to the painter’s hand. “Place des Lices, St. Tropez” is therefore both a document of study and a declaration of independence, a laboratory in which Matisse tests how far emotion can push theory without letting the structure collapse.

Composition: A Stage Framed by Trees

The image is built like a proscenium stage. Two tall trunks flank the left and right edges, their canopies sweeping across the upper margin like curtains. They bend the viewer’s gaze toward the light-filled center where the wall and gate hold steady as architectural anchors. Behind them, a low procession of roofs and hedges steps back to the horizon and culminates in the tower that rises as a single vertical accent. What might be a busy civic square is emptied of people to let the eye travel unimpeded, moving from the cool foreground shade into the hot middle ground and back to the serene, milky sky. Diagonals from rooflines and pavements guide the gaze in gentle arcs, while the central void of sky keeps the entire design breathing rather than congested.

Light and Color: Violet Shadows and Citrus Heat

Southern light is the protagonist, and Matisse paints it through complementary relationships. Shadows are not gray but saturated violets and blue-greens; sunlit stucco is not white but a chord of lemon, cream, and pale peach. These oppositions make the surface vibrate. Temperature shifts, rather than heavy modeling, carve forms: a warm plane turns as it cools into shadow; a tree trunk that could have read as black recedes into purples and forest greens; the sky becomes a woven fabric of lavender, turquoise, and soft white. The sense of heat rising from the wall is not described by narrative detail but transmitted through color temperature alone. As viewers, we feel the glare and the relief of shade because yellow and violet, orange and blue, red and green are constantly playing off each other.

Brushwork and Surface: From Division to Decision

Three broad manners of touch interact across the canvas. Small, separated touches in the sky maintain the optical shimmer that Matisse inherited from Divisionism. Broad, dragging strokes articulate the planar calm of the wall and street so that the architecture does not dissolve into sparkle. More calligraphic sweeps, especially in foliage and trunks, restore the rhythm of drawing within the color masses. Nothing is over-blended; edges breathe; the paint retains its material presence. The coexistence of these touches turns the surface into a lively field that remains legible, a crucial balance for a painter finding a path from method to expressive freedom.

Drawing with Color: Structure Without Heavy Contour

Unlike earlier Paris interiors where black lines carve shapes, here drawing is largely achieved by adjacency. The gate’s rhythm, the crenellations of roofs, the palm’s splayed leaves, and even the profile of the tower are defined because warm sits next to cool and light next to dark. This technique keeps the scene sunstruck. Heavy contour would have deadened the chroma and pulled the eye away from the experience of light, which is precisely what Matisse wants to foreground.

Rhythm and Motif: Trees as Choreography

The trees do not merely decorate the edges; they choreograph space. The umbrella pines’ canopies form a canopy that suggests shelter from the midday glare, while the palm on the left supplies a signature of place and a counter-rhythm to the more compact pine foliage. The thick trunk at the right anchors the composition like a column, yet it never feels ponderous because its surface is infused with cool violets and greens that echo the surrounding atmosphere. These botanical motifs weave a slow visual music that guides the viewer into and around the square.

Architecture as a Light Machine

The plain wall and iron gate are more than civic detail. They are the central instruments in Matisse’s light machine. The wall offers a high-value plane where subtle variations of temperature read with exceptional clarity, making the bright center of the painting feel almost incandescent. The gate, painted in cooler greens, provides a tonic interval inside that brightness. Together they establish a stable chord around which the rest of the composition harmonizes, allowing the surrounding hues to flare without disintegrating the whole.

Space and Perspective: Shallow Depth, Expansive Air

The painting organizes a clear foreground, middle ground, and background but maintains a relatively shallow depth. Planes are stacked rather than continuously tunneled into space. This intentional flattening, inherited from Japanese print aesthetics and from Gauguin’s example, frees Matisse to let color operate decoratively across the surface while still keeping the scene believable. The central field of sky functions as positive negative space, the kind of audacious openness that will later underpin his Nice interiors and, decades on, the luminous expanses of his paper cut-outs.

Mood and Meaning: Civic Calm and Sensory Luxury

Place des Lices is a public arena, but Matisse paints it as a private experience of civic calm. The absence of people removes anecdote and makes room for a meditative encounter with shade and glare, coolness and heat, stone and foliage. Luxury here does not mean ornament. It means the luxury of air, of time, and of the body’s quiet oscillation between sunlight and shadow. The square becomes a kind of modern Arcadia where the everyday architecture of a small town is transfigured by color into a theater of sensation.

Relationship to the St. Tropez Cycle

Viewed alongside canvases such as “The Gulf of Saint Tropez,” “View of Saint Tropez,” and studies for “Luxe, calme et volupté,” this work reveals a different emphasis within the same summer’s experiments. On the coast Matisse often lets form dissolve into scintillation; in the square he tightens the structural armature so that color can strike more daring notes without losing clarity. The painting functions as a bridge between the optical discipline he admired in Seurat and the emotionally charged, high-chroma language that would explode in the 1905 Salon d’Automne and earn the cohort the name Fauves.

The Science Beneath the Sensation

Several principles of color science quietly drive the effect without announcing themselves. Simultaneous contrast elevates chroma by pairing complements; optical mixture lets small touches of unmixed pigment blend in the eye at viewing distance; warm–cool modulation substitutes for laborious tonal modeling and mirrors the way Mediterranean light actually behaves on reflective surfaces. Matisse deploys these tools in the service of sensation rather than as demonstration, which is why the painting feels alive rather than didactic.

Materials and Handling: A Painter’s Notes

A warm, light ground seems to glow through thin passages, giving unity to the palette and helping light bloom from within the paint film. Dry scumbles, notably lilac dragges over green in the foliage, lend translucency and the breath of air between leaves. The tower and distant roofs are blocked with only a handful of planes, a lesson in economy that prevents the eye from getting trapped in trivia. Edges range from crisp to feathered, guiding attention and creating a rhythm of focus and release that keeps viewing dynamic.

Iconography of a Modern Paradise

St. Tropez offered Matisse a synthesis he chased throughout his career: classical order and modern freedom. Palms, high walls, and tiled roofs carry the timeless vocabulary of the Mediterranean. Broken color, temperature clashes, and the elastic placement of forms declare early twentieth-century modernity. In this meeting of the enduring and the experimental we can already sense the painter who will later develop the serenely radical language of the Nice interiors and ultimately the chapel in Vence.

Reading the Foreground Band: Climate in Color

The violet-blue band of shade across the lower register is not a mere base strip; it is the painting’s climate index. The coolness of the band is arranged so that it calibrates the burn of the wall. Anyone who has walked a southern square at noon recognizes the sensation encoded here: step out of shade into the blaze, then retreat. Matisse translates that small bodily drama into a temperature symphony, which is why the image feels physically persuasive.

The Role of Emptiness: Negative Space as Modern Design

One of the most contemporary aspects of the picture is its confident use of emptiness. By refusing narrative detail—no market stalls, no promenaders—Matisse yields the stage to color relationships. The large field of sky is not an absence but a reservoir of light that feeds every other hue in the painting. This embrace of negative space anticipates modern graphic design and explains the work’s abiding freshness: the image is memorable because it is structurally simple and chromatically daring.

Why It Still Matters

For art history, “Place des Lices, St. Tropez” records the inflection point where Matisse’s exploration of optics becomes a vehicle for emotion. For practicing painters, it is a primer in how to frame a scene, how to balance hot and cool, how to vary touch without breaking unity, and how to let color carry form. For the general viewer, it remains what it first promised: a radiant invitation to inhabit a summer square where architecture, air, and trees converse in the language of color.

Conclusion: A Sunlit Manifesto Before the Leap

This canvas distills the encounter between southern light and a mind ready to reimagine painting. Trees frame like curtains; a wall and gate shine like a stage; a violet shade cools the floor; and above all, color proves capable of constructing space, describing surfaces, and transmitting mood without reliance on the heavy labor of outline and tonal shading. One year later Matisse will astonish Paris as a Fauve. “Place des Lices, St. Tropez” shows the thoughtful, joyous step just before the leap.