Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

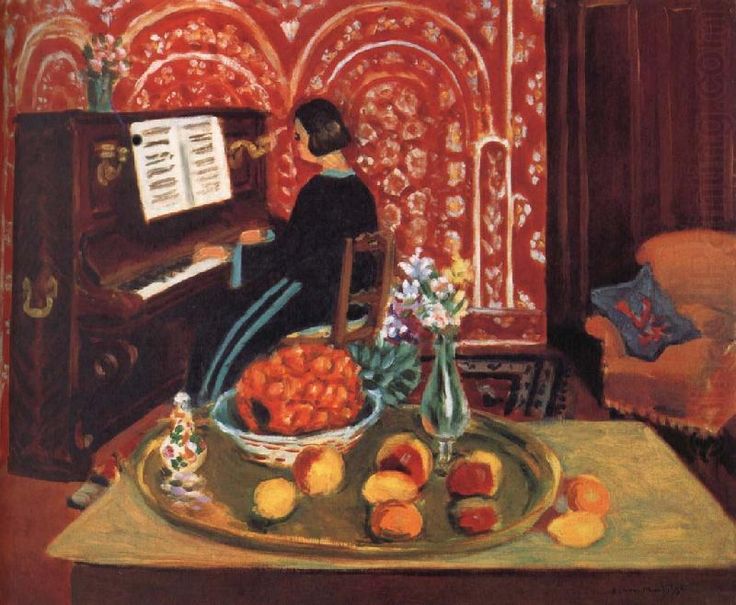

Henri Matisse’s “Piano Player and Still Life” (1924) brings two of the French master’s favorite Nice-period motifs into a single, glowing interior: music and the tabletop arrangement. A pianist sits in profile at an upright instrument set against a vermilion wall patterned with white floral arabesques and arching niches. In the near foreground, a low table holds a brass tray laden with peaches and apricots, a heaped basket of oranges, a glazed faience bottle, and a slim vase of garden flowers. Between these poles—sound and sight, action and repose—Matisse composes a room that hums with rhythmic repetitions and calibrated color. The painting is not a narrative scene so much as an orchestration, a demonstration of how figure, décor, and still life can be tuned to the same key.

Historical Context and the Nice Vocabulary

By 1924 Matisse had spent several years refining the luminous language of the Nice period: ambient Mediterranean light; shallow, layered space; patterns pressed forward like textiles; and a democratic surface in which people, furniture, fruit, and flowers enjoy equal pictorial dignity. Music is central to this vocabulary. He paints guitars, mandolins, and pianos not only because they are beautiful objects but because the concepts of rhythm, harmony, and tempo translate directly into color, interval, and repetition. The still life likewise becomes a testing ground for relation and balance. In “Piano Player and Still Life,” these two strands intertwine, allowing Matisse to play a duet between a human gesture and objects that keep their own visual beat.

Composition as a Duet of Depths

The composition divides into two planes that talk to each other across the surface. At left-midground, the pianist anchors the room in a pocket of deep, warm reds and browns; at front-right, the still life occupies a bright platform that begins just at the viewer’s edge. The brass tray, drawn as a large, tilting oval, pulls the foreground toward us, while the keyboard and sheet music drag the eye back into space. This push-pull is intentional. It keeps the surface alive, makes us aware of looking, and rehearses the painting’s theme: near and far joined in a single chord.

Matisse sets up a clear directional flow. We move from the tray’s fruits to the vase, across the greenish tabletop toward the figure’s hands, up to the sheet music, then back into the patterned wall that swells like a red acoustic shell. The sofa at far right, with its soft ochres and small blue cushion, closes the circuit and sends the eye forward again to the tray. Nothing interrupts this circulation; every object is positioned to maintain the room’s measured tempo.

Pattern as Architecture

The vermilion wall, alive with white floral medallions and soft arches, provides the room’s architecture. Rather than pushing backward as a traditional background, it presses forward like a tapestry. The repeated arches rhyme with the rounded shoulders of the pianist, with the rim of the brass tray, with the wicker bowl of oranges, and with the goblet-shaped vase. Pattern is not mere decoration; it is the grammar that holds the whole together. On the table, the round fruits echo the wall’s blossoms, while the tray’s thick red border repeats the wall’s hue in a cooler, metallic register. Even the carved designs on the piano’s side and the arabesque of the faience bottle participate in the conversation, tightening the weave of visual relationships.

Color Climate and Temperature Control

Color is the painting’s climate. The red wall radiates heat, enriched by the warm mahogany of the piano and the saturated oranges and peaches that glow on the tray. To cool this atmosphere, Matisse deploys greens and blue-greens in the tabletop, the stems and leaves of the bouquet, and the slim stripes in the pianist’s skirt. The bouquet itself—white with touches of violet and rose—acts as a chromatic bridge: it keeps company with the warm wall yet leans toward cooler notes that aerate the center of the picture. The sofa’s ochre and powder-blue cushion contribute a low, restful chord at the right margin that balances the heat at left.

Matisse avoids harsh black. Even the deepest darks in hair, bench, and piano are infused with color, allowing them to sit inside the harmony rather than cut across it. Small highlights—the shine on the tray’s lip, the glassy flare on the vase, the pale glints along the keyboard—act like overtones that tell us the room is well lit without dragging us toward naturalistic description.

The Piano and the Player

The upright piano is rendered as a solid block with beveled edges that catch slow, warm light. Matisse keeps detail to a minimum: a few carved elements, brass handles, the fan of keys, and the oblique rectangle of sheet music pinned to the rack. This economy protects the painting from fussy narrative; the instrument reads as an engine of rhythm, not a portrait of a particular make. The keyboard’s black-and-white alternation establishes a crisp, visual beat aligned with the player’s hands.

The musician, seen in profile, wears a dark dress trimmed with cool blue stripes, a perfect chromatic foil to the red surround. Her posture is compact and intent; the head inclines toward the music, and the hands hover in a phrase caught on the beat. Matisse is not after virtuoso performance. He wants the look of absorbed attention—the quiet, modern dignity of someone engaged in a discipline inside a tuned room.

The Still Life as Counter-Melody

Across the foreground, the still life offers a counter-melody to the piano’s steady measure. The brass tray, its red inner band thickly painted, carries a constellation of peaches and apricots. Their positions—some grouped, some spaced—create syncopations in the golden oval. At the tray’s far edge, a wicker bowl is heaped with oranges, their compact forms stacking into a warm crescendo. The glass vase, narrow at the neck and swelling toward the base, holds a small bouquet that echoes the wall’s blossoms while asserting its presence with cool and white notes. A little faience bottle with floral decoration adds a miniature of the room’s entire language: pattern, curve, and saturated color balanced in a toy scale.

These objects are not inert. The brushed highlights on the fruit and the reflections on the tray keep their surfaces breathing; the bouquet’s petals are dabbed in rapid, staccato touches; the wicker is indicated by broad, basket-weave strokes. Matisse’s touch carries the same mix of deliberation and spontaneity that a musician brings to phrasing.

Ambient Light and the Refusal of Theatrical Shadow

The Nice period is marked by benevolent, ambient illumination—light that fills, rather than attacks, the room. In this painting shadows are soft and transparent: a pinkish dark under the tray, a hummed shadow on the wall below the sheet music, a deeper pool behind the piano bench. The effect is to keep every colored shape available to the eye. Nothing is lost to glare or plunged into obscurity. Because light is even, color does the expressive work. The room glows; it does not perform.

Space by Layers, Not Vanishing Points

Depth is built by overlapping planes and temperature shifts rather than strict linear perspective. Front: the tray and tabletop tilted toward us; middle: the bouquet, bottle, and basket; farther back: the pianist and the instrument; behind all: the patterned wall and the shadowed recess with sofa. The floor itself is only barely indicated, allowing the whole to read as a set of suspended layers—like staves in a score—rather than a tunnel. This approach puts the viewer within arm’s length of the fruit and tray while still granting the pleasure of looking past them toward a human action and a warm, enclosing wall.

Drawing and the Economy of Means

Matisse’s drawing is laconic and exact. The oval of the tray is pulled in one confident sweep and reinforced where necessary; the vase and faience bottle are described with elastic outlines that swell where the brush slows. On the piano, the keys are quick upright dashes, enough to establish the alternating rhythm without counting. The figure is modeled with a few planes and the slightest turn of the head; hair is a soft dark mass; the collar is a triangular light that lifts the face. This economy is not parsimonious; it simply leaves room for color to carry emotion and for pattern to carry structure.

Rhythm, Repetition, and the Music of Looking

The painting is musical at every level. Keys repeat; wall blossoms repeat; fruits repeat; arches repeat; the tray’s border repeats the wall’s red; the bouquet repeats the wall’s small lights in a livelier tempo. Between these beats, Matisse leaves rests—broad planes of tabletop, patches of unpatterned wall, the dark mass of the dress—so that the eye does not tire. The viewer’s route through the room has the shape of a phrase: begin at the tray, rise to the bouquet, move to the hands and score, descend across the red wall to the sofa, and return to the tray. With each circuit the interdependence of parts—the duet between player and objects—becomes clearer.

The Ethics of Poise

Matisse’s Nice interiors often model a gentle ethic: composure, attention, and care for the environment that supports them. “Piano Player and Still Life” is exemplary in this regard. The musician practices without show; the room is arranged with modest luxury—flowers, fruit, a polished tray; and everything is bathed in warm, steady light. The painting proposes that beauty is available in ordinary rituals of cultivation when space, color, and rhythm are tuned with affection.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The surface records a variety of speeds and pressures. The red wall is covered in broad, buttery passages into which white motifs are pressed wet-in-wet, leaving soft halos at their edges. The brass tray’s lip is loaded and dragged, forming a slightly raised ridge that catches light in reproduction as it would in the gallery. Fruit are done with turning strokes that wrap their forms; the bouquet’s stems are quick, vertical flicks. The piano’s flat planes are thinly scumbled, letting the weave of the canvas peep through like the grain of wood. This physicality keeps the painting from becoming a merely decorative design; it remains a made object, tactile and temporal.

Comparisons Within 1923–1924

Set beside Matisse’s 1923 “The Piano Lesson” or “Woman with Violin,” this work opens the space and deepens the color key. It is richer and darker than the breezy open-window pictures, and more architecturally patterned than the intimate dressing-table scenes. Compared with the odalisques, it shifts emphasis from the pose of the body to the choreography of objects and actions. Across all these canvases, however, the constant is Matisse’s belief that painting can translate daily life into a lucid harmony without inflating it into drama.

How to Look, Slowly

Start with the foreground tray. Let your eye circle its crimson rim, count the fruits, and notice how cool greens and warm yellows bounce across the metal. Step to the wicker bowl and feel the oranges crest into a small mountain. Rise through the slender vase to the bouquet’s cool whites and violets, then cross to the pianist’s hands and the fan of black-and-white keys. Climb to the sheet music—unreadable but sufficient—and then drift outward into the vermilion wall where blossoms expand like echoes. Slide to the ochre sofa and blue cushion before returning to the tray. Repeat as long as the picture holds you; the room’s tempo rewards every circuit.

Meaning Through Design

The painting’s meaning lies in its design. The player and the still life are not two subjects but two voices in one chord. The fruit and flowers do not decorate the musician; they parallel her discipline with their own poised arrangement. The red wall does not overwhelm; it sustains a key in which cool notes can sparkle. Everything here is relation—proximity, overlap, echo, contrast—and relation is what allows the scene to feel whole, intelligible, and humane.

Conclusion

“Piano Player and Still Life” is a lucid summation of Matisse’s Nice ideals. Ambient light replaces theatricality; pattern becomes architecture; color carries emotion; drawing remains spare and exact; and daily rituals—music, arranging flowers, setting fruit on a tray—are given the dignity of art. The painting does not tell a story about a particular person at a particular hour. Instead, it composes a state: a tuned room where sound, sight, and touch meet in calm accord. Nearly a century later, it still teaches a usable lesson—care for the relationships in front of you, and ordinary life will begin to sing.