Image source: wikiart.org

A Miracle Drawn in Lines: Introducing Rembrandt’s Scene

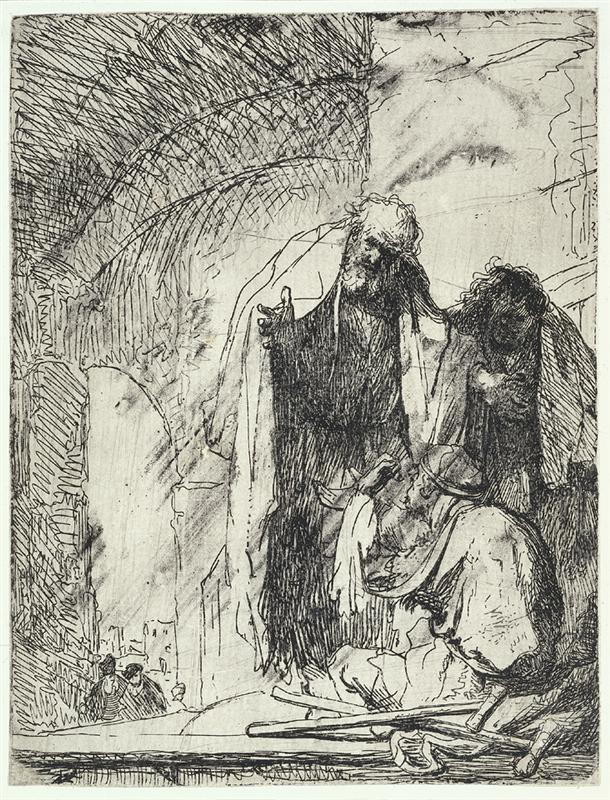

Rembrandt’s “Peter and John at the Gate of the Temple” (1629) captures the biblical episode from Acts 3 with the urgency and intimacy of a moment witnessed at arm’s length. Two apostles pause at the threshold of Jerusalem’s Temple and face a lame beggar seated on the steps. In a few blazing strokes, Rembrandt turns architectural space into a stage, etching into copper a drama where poverty meets authority, habit meets revelation, and a hand about to lift meets a world about to change. The plate is small, the means are spare, yet the impression expands in the mind like a bell’s resonance. It is an early statement of his lifelong conviction that the greatest stories happen not in crowds and pageantry but in faces, hands, and the light that discovers them.

The Scriptural Moment and Why It Matters

The story is brief and unforgettable. A man lame from birth is carried daily to the Temple gate called Beautiful to ask for alms. Peter and John fix their eyes on him. “Silver and gold have I none,” Peter says, “but such as I have give I thee: In the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth rise up and walk.” It is a scene of attention before it is a scene of power. Rembrandt honors that order. He does not etch the man leaping; he etches the pause in which a gaze becomes gift and a hand, still near the ground, prepares to lift. In that pause he finds the psychology of faith and the social shock of compassion.

A Composition Hinged on a Threshold

Everything in this print orients you to the gate. A sweeping arch rises at left like a stone canopy, a grid of cross-hatching suggesting its shadowed coffering. The curve drives the eye downward toward the narrow passage into the city where two tiny figures, perhaps passersby or assistants who carried the lame man, shrink into distance. To the right of the arch Rembrandt stacks draperies, bodies, and steps in a dense vertical, the apostles towering like columns of felted light and the seated beggar forming a rounded base. Across the bottom he scripts a ledge with scattered staffs and a bare foot, a proscenium that separates the viewer’s space from the miracle’s stage. The entire composition hangs on the idea of crossing: from outside to inside, from need to gift, from expectation to surprise.

The Apostles as Vectors of Attention

Peter and John are not grandly individualized, yet each bears a distinct attitude. Peter, at the right front, is larger, his drapery falling in decisive planes that carry the weight of command. His head tilts, beard forward; his arm, wrapped in the mantle, forms a vector down toward the beggar’s hand. John stands slightly behind, a dark, contemplative mass. His posture is more vertical, his face almost eclipsed within the heavy hatching of his hood. Together they create a polarity—active proclamation and contemplative assent—through which the miracle will flow. The drama plays across their gestures rather than their attributes; Rembrandt declines halos and points of doctrine in favor of the grammar of bodies.

The Beggar’s Body as the Center of the Question

The lame man sits at the hinge of the scene, near the steps, knees up, a cap pulled low, drapery bunched around the hips. His feet, drawn with a few decisive strokes, splay outward in a way that reads instantly as long habit rather than theatrical pose. One hand reaches loosely as if expecting coins; the other props his tilted torso. The question his body asks is not only “Will you give?” but also “Does the world contain any other answer than alms?” Rembrandt’s composition lets that question hang in the air as thickly as the shadow under the arch.

Line That Thinks, Hesitates, and Decides

This is an etching that remembers the movement of the hand that made it. Rembrandt lays down quick parallel hatch for shadowed architecture, then scumbles lines into a net to conjure the arch’s depth. Around the apostles’ mantles the strokes slow and lengthen, becoming sweeping tracks that feel like fabric caught by light. In the beggar’s drapery they shorten and angle unpredictably, registering the restless bunching of cloth on stone. Across the plate you can spot exploratory marks, restatements of contours, and places where the needle lifted mid-stroke. Instead of scrubbing away these traces, the artist keeps them as a record of looking that discovers rather than dictates.

Plate Tone as Weather and Sanctity

Many impressions preserve a veil of plate tone—a film of ink left intentionally on the copper before printing. Rembrandt manipulates this veiling to breathe air into the scene. The tone thickens beneath the arch, turning the space into a cavern of reverent dusk; it thins around the apostles’ heads so their presence feels translucid, like forms catching a shaft of light; it dapples the paving where the staffs lie, a reminder that Temple courts are made of dust as well as glory. With almost no white highlights, the atmosphere glows from within, as if holiness here were a quality of the air rather than a spotlight from elsewhere.

Architecture as Theology in Stone

The gate is not a mere backdrop. Its sweep and mass serve idea as well as perspective. The arch’s large curve frames a small act, declaring that institutions are at their best when they hold space for encounters that change lives. The ladder of steps tightens that thesis, stacking the scene into levels of meaning: civic ground, sacrificial threshold, the niche where the poor wait, and the narrow opening where the city’s bustle continues, unaware. The apostles stand between sanctuary and street, translating one to the other.

The Dialogue of Hands

Rembrandt writes conversations in hands. Peter’s hand, partly veiled by his mantle, points and readies; John’s darker hand rests like a seal on the revelation about to be spoken; the beggar’s hand opens in practiced asking. The triangle among them is the scene’s syntax. Money would travel in a small downward arc. Instead, power and mercy will travel in a lifting arc, and you can see it planned in the gesture’s geometry. The visual sentence reads: look at us, receive, rise.

The Ethics of Attentive Looking

The print’s moral force comes from its refusal to sensationalize. Rembrandt does not display deformity, does not belabor pity, does not flood the plate with spectators. He chooses a vantage that privileges proximity over spectacle and listens more than it preaches. That ethics of looking—direct, patient, unafraid of silence—will become the hallmark of his mature storytelling and portraiture. Here, in his twenties, he is already practicing it with an apostolic calm.

The Sound Inside the Silence

Though copper and ink cannot literally sound, this image hums with implied noise. You can hear the faint clatter of staffs laid aside, the murmur of footsteps under the arch, the whisper of cloth as Peter shifts his weight, the city’s distant trade flickering at lower left. Over those textures runs the stillness that partners real attention. Rembrandt orchestrates this audio through densities of hatch, allowing the darker pools to muffle and the pale reserves to ring.

A Gate Called Beautiful and the Beauty of Restraint

Acts names the threshold “Beautiful,” and Rembrandt answers with restraint rather than embellishment. No carved reliefs, no ornate inscriptions, no architectural vanity press forward. Beauty here is a function of use: the arch shelters, the steps hold, the light finds what matters. This aesthetic of usefulness places the print on the same axis as the story itself, where the most valuable gifts are not objects but transformations.

Scale, Proportion, and the Choice of Intimacy

The apostles are large relative to the gate, and the beggar is large relative to the apostles’ feet. This slight distortion is purposeful. It presses the sacred encounter forward, asking us to weigh it more heavily than the impressive stonework around it. The intimate scale of the plate inside the viewer’s hands reinforces the choice. You do not admire this scene from across a gallery; you read it like a letter. The miracle arrives in the register of conversation.

The Lower Ledge as the Viewer’s Threshold

Rembrandt often stages a foreground plank or ledge that doubles as the viewer’s perch. Here, that shallow strip across the bottom carries staffs and a foot, items that are both boundary and invitation. The ledge keeps us from falling into the scene while giving us the tactile feel of material on stone. It also implies our own responsibilities: the tools of walk and work lie within reach, as if to suggest that what happens beyond—attention, speech, lifting—might be ours to enact when the sheet is closed.

Theological Depth Without Iconographic Clutter

Because Rembrandt avoids badges and inscriptions, he lets theology arise from action. Peter’s refusal of silver and gold is visible in the absence of coin. John’s contemplative backup reads in the silence of his posture. Faith’s efficacy becomes legible as a geometry of bodies oriented around a need. The plate thus serves devotion without depending on symbol literacy. Any viewer acquainted with pain, waiting, and the instinct to look away already understands the problem and can learn from the apostles’ answer.

Relation to Rembrandt’s Other Early Sacred Prints

This etching stands alongside other early biblical subjects where thresholds concentrate meaning: “The Flight into Egypt” sketched as a night crossing, “The Presentation in the Temple” staged at a lit interior step, and small Passion scenes that compress eternity into a gesture. The recurring choice reveals a program. Edges—of rooms, roads, and responsibilities—are where character shows. By returning to gates and steps, Rembrandt trains himself to find the instant when an ordinary surface becomes the brink of change.

The City Beyond and the World Unaware

At lower left, tiny figures cross an open square or corridor of the Temple’s courts. They are drawn with a few scratches yet read as fully human—a hat, a turning head, a sliver of conversation. Their miniature life provides counterpoint to the main trio. Not all holiness is recognized as it occurs; much of the world’s traffic keeps moving. The print holds both truths in a single field: a miracle intimate enough to miss, a city large enough to miss it.

How the Print Teaches Us to Look

The etched paths choreograph vision with quiet authority. You begin under the arch, slide along its shadow, drop to the apostles’ faces, follow the fall of drapery to the beggar’s hands and feet, and then drift across the lower ledge where staffs lie idle. Next your eye slips out through the small opening into the city and circles back. Each loop repeats the story’s logic: sacred attention contracts, gives, and then reenters the world enlarged. The choreography educates the gaze in the same way the miracle educates the heart.

The Human Temperatures of Ink

Rembrandt’s ink has temperatures even in monochrome. Dense, overlapping hatch reads as warm, human mass in the apostles’ cloaks; open, lightly bitten lines feel cool in the distant architecture; mixed scumbles over the central wall create a chalky mid-zone like plaster warmed by sun and voices. These temperatures organize feeling: firmness in the apostles, vulnerability in the beggar, neutrality in the stone that outlasts them all.

Why This Early Etching Still Finds Us

The image endures because it identifies the hinge on which mercy turns: attention. The apostles give their gaze before they give their words, and the beggar becomes more than a type at the exact moment he is truly seen. Rembrandt’s line honors that economy. He gives us just enough to recognize a world and then loans us his concentration so that we might practice it in ours. The gate called Beautiful becomes, on this small plate, the frame through which our own eyesight might be made beautiful—clearer, steadier, more willing to stop.