Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

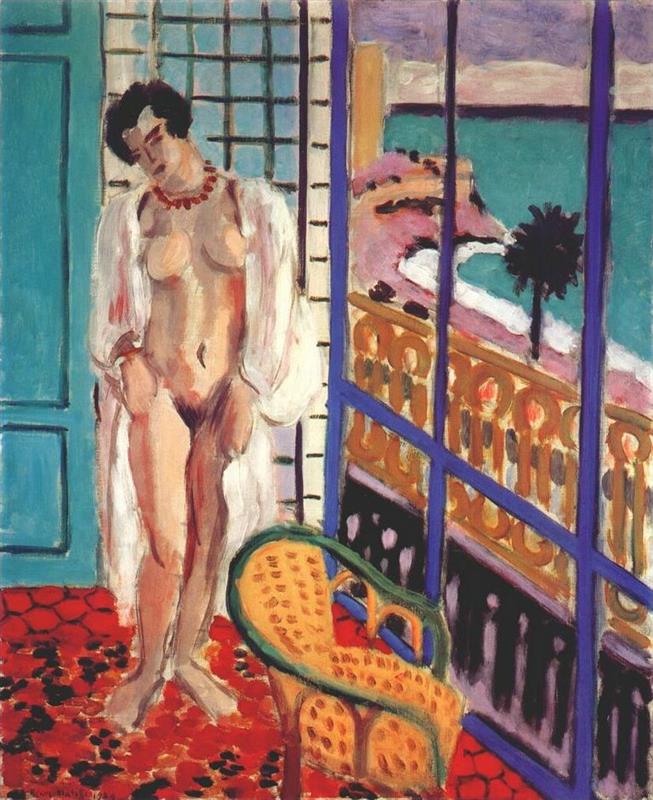

Henri Matisse’s “Pearly Nude” of 1929 is a luminous summation of the painter’s Nice years, when color, pattern, and the figure were orchestrated into interiors that feel both intimate and architectural. A model, her skin tuned to pearly pinks and grays, stands just inside a balcony door. Behind her, a gridded screen and turquoise door flatten the wall into clear geometry. To her right, a brilliant cobalt balustrade frames a view of the Mediterranean where sea, sky, and a single palm tree are simplified into layered bands. A wicker chair in the foreground bends like a treble clef over a cinnabar carpet tiled with dark hexagons. Everything is shallow, frontal, and charged by color. The painting is not a narrative but a calibrated climate where warm and cool, curve and grid, body and architecture are made to cooperate.

The Nice Studio As A Theater Of Light

By the late 1920s Matisse’s rented rooms in Nice had become laboratories for a new pictorial language. He replaced deep perspective with a series of hinged planes—doors, shutters, grilles, screens—that could be rearranged like stage flats. The Mediterranean light reflected off sea and stucco, producing ambient illumination rather than directional spotlight. “Pearly Nude” captures this laboratory at full maturity. The interior is reduced to a few structural elements that hold their own against a compelling exterior view. The gridded screen is not a mere accessory; it is a metronome for looking. The balcony rail is not decoration; it is a structural chord spanning foreground to distance. The model absorbs this light and structure, becoming the point where the room’s energies collect.

Composition As A System Of Vectors And Bands

The composition is organized by two dominant systems. Inside the room, verticals and perpendiculars govern: the turquoise door at left, the pale grid behind the model, the cobalt mullions of the balcony frame. Beyond the frame, the world resolves into horizontal bands: the aqua water, the strip of shore, the violet sky. These two systems intersect at the figure. Her diagonal head tilt and the gentle curve of her robe offer a flexible counterpoint to the rigid architecture. The wicker chair curves forward like a question mark, echoing the balcony’s arabesque railing and balancing the figure’s solid stance. The red floor, laid in hexagonal tessellation, rises toward the picture plane and provides a rhythmic base that prevents the eye from falling out through the balcony.

Color As Architecture And Temperature

Color is the painting’s architecture. The floor is a hot world of cinnabar and maroon; the wall is cooled by the turquoises of door and screen; the balcony and window grille thrust a strong cobalt vertical through the middle right; the sea holds a calmer, saturated aqua that reads as distance; the sky, a mauve-gray lid, quiets the top edge. The model’s body is modulated within this temperature map. Warm rosy notes pool across chest and thigh; cool gray-violets gather in shadow at the ribcage and groin; a pale highlight catches at the shoulder and cheek. Because every hue borrows from its neighbor—the sea reflecting slightly into the torso’s right contour, the red floor warming the ankles—the palette reads as one climate rather than patches. The result is a room that feels both open to the Mediterranean and held together by a stable internal weather.

The Balcony As Organizing Device

Matisse’s balcony motif recurs throughout the Nice period because it allows him to set an interior grammar against exterior bands. Here the cobalt structure performs several roles at once. Its vertical bars keep the eye from sliding out to sea too quickly. Its golden, scalloped railing echoes the wicker chair’s curves, knitting foreground to view. Its color—neither as warm as the floor nor as cool as the sea—serves as a hinge, mediating between inside and outside. Through these means the balcony becomes less an architectural feature than a pictorial instrument for balance.

Pattern And Grid As Meter

Pattern in “Pearly Nude” is a system for keeping time. The floor’s repeating hexagons provide a steady beat, faster at the bottom where shapes are larger, slower as they compress toward the balcony. The screen’s light grid beats at a slower tempo, anchoring the figure in a calm field so flesh can read cleanly. The balcony’s verticals supply another rhythm layered over the first two. These meters are not decorative distractions; they are the very devices that allow the body’s soft volumes and the sea’s quiet band to coexist on a flat plane without confusion.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Edge

Matisse’s authority lies in his contour. The figure’s outline is written with a line that tightens and relaxes like breathing. It is firm at wrist and jaw, looser at calf and robe, slightly insistently dark where the left thigh meets the cool screen so the limb will not dissolve. Interior lines are minimal—just enough to register navel, clavicle, and the turn of the breast. The chair is drawn more briskly, its wicker and wood stated with elastic strokes that leave the weave of the canvas visible. The balcony bars are straight but hand-made, their slight irregularity saving them from mechanical chill. Everywhere, line functions less as boundary than as seam where colors meet and exchange energies.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The picture is bathed in the mild, ambient light of Nice. There are no theatrical shadows; instead, values turn by temperature. Cool violets, thinly laid, pool in the model’s hollows. Warm peach rises where light reflects off the floor. The face is modeled with gentle half-tones and set off by the coral necklace, which doubles as a small rhythm of crimson dots. Even the exterior is subdued: the sea glows but does not sparkle, the sky is veiled, and the white surf is rendered as a simplified ribbon. By compressing value contrasts, Matisse asks color and contour to describe volume and atmosphere. The effect is a serene clarity in which everything can be looked at without glare.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Depth is shallow by intention. The floor tilts up; the balcony stops the eye like a screen; the horizon is a narrow band pinned to the picture’s upper third. Overlap does the work of persuasion—chair in front of balcony, figure in front of grid, rail slicing across view—without allowing the scene to open into deep perspective. This productive flatness keeps the viewer present at the surface, where the relationships among colors and shapes are legible and reversible. The painting becomes a place to think with the eyes rather than a passage through which to travel.

The Figure As Harmonic Center

The model is the harmonic center of the ensemble. Her pose—weight dropped into the right hip, head tilted, hands loosely gathered—has an everyday poise that refuses melodrama. The translucent robe, painted in thin whites that admit the wall’s color, softens her silhouette without hiding it. The coral necklace is less ornament than punctuation, a small warm phrase that repeats the floor’s heat near the face. Matisse neither idealizes nor anatomizes; he calibrates. The figure is placed where grid, bar, and band meet, so that the human contour becomes the reconciliation of the painting’s structural systems.

The Chair As Counter-Melody

The wicker chair is a virtuoso counter-melody. Its curving back and seat echo the body’s arcs, while its yellow and green notes pick up the gold of the balcony and the cools of the interior walls. The chair’s arabesque opposes the rectilinear screen and bars, preventing rigidity. By tilting the chair toward us, Matisse adds a near element that keeps the surface from feeling like a pasted collage. The chair “speaks” with the balcony railing, and together they play an ornamented duet across the room’s middle register.

Evidence Of Process And Earned Equilibrium

Close looking reveals small revisions that reveal how the calm was constructed. A darker restatement along the left thigh clarifies where flesh meets the grid. The chair’s front leg is reinforced to prevent it from floating on the red ground. The balcony’s cobalt uprights appear adjusted in thickness so that their rhythm does not compete with the figure’s internal accents. The surf’s white ribbon is softened where it meets the palm so the exterior will remain a unified band, not a landscape vignette. These quiet corrections show Matisse tuning intervals, adjusting weights until differences cooperate.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

The mood is contemplative and domestic rather than erotic or dramatic. The model’s lowered head invites a slower pace of viewing; the sea, ever-present yet disciplined by vertical bars, promises openness without dispersal. The viewer’s eye moves in a circuit: from the cool door to the warm floor, up the figure’s contour, across the cobalt bars to the aqua band, down the golden railing to the wicker chair, and back into the room. Each round discloses new relations, such as the way the necklace’s coral echoes a hexagon in the carpet, or the way a violet in the sky quiets a shadow across the stomach. The painting is built for return.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Pearly Nude” converses with several Matisse themes. It reprises the balcony images that began in the teens and blossomed in Nice, where interior and exterior could be opposed and reconciled. It shares with the odalisque series the use of patterned floors and chairs to measure the body’s curves. It also gestures toward the planar logic of the 1930s—broad bands, declarative color, interlocking silhouettes—that would culminate in the late paper cut-outs. Compared with the saturated patterning of 1925, however, this work feels clarified; the pattern is present but disciplined, the palette opulent yet controlled.

Ornament And The Ethics Of Pleasure

Much has been written about Matisse and decoration, yet “Pearly Nude” clarifies that ornament here is a way of distributing attention fairly across the surface. The balcony’s pattern is not a flourish; it is a structural bridge. The floor’s tessellation is not noise; it is meter. The necklace is not fetish; it is a localized rhythm that tunes the face. Even the palm outside is simplified into a dark emblem to balance the interior chair. Pleasure in this painting is not a flight from thought; it is a consequence of clarity.

Material Touch And The Differentiation Of Things

Matisse differentiates materials through tailored handling. Flesh is laid in creamy, semi-opaque strokes that knit into a single field; the robe is thin, translucent, and quick; the turquoise door is more densely painted, its planes articulated with blunt verticals; the balcony bars are flat and opaque, giving them architectural authority; the sea is glazed enough to glow but not so shiny as to break the plane. These calibrations give the eye a quiet sense of tactility without violating the priority of the surface.

Why The Painting Endures

“Pearly Nude” endures because it converts oppositions into harmony without flattening their difference. Warm and cool, interior and exterior, grid and curve, pattern and band, human softness and architectural hardness—each is granted its own character and then persuaded to collaborate. The result is a room that breathes, a figure that feels inevitable within it, and a view that promises distance yet keeps faith with the surface. The painting models a way of seeing that is generous, lucid, and renewable.

Conclusion

In 1929, Matisse staged a quiet triumph. With a pearly-skinned model, a cobalt balcony, a red patterned floor, and a slice of the Mediterranean, he composed an interior where color is architecture, pattern is time, contour is breath, and light is kindness. Nothing in the canvas clamors; everything cooperates. The viewer is invited not to witness an event but to inhabit a balance. “Pearly Nude” is thus both an emblem of the Nice period and a blueprint for the clarity that would guide Matisse’s later work.