Image source: artvee.com

Introduction: Advertising and Art Nouveau Collide

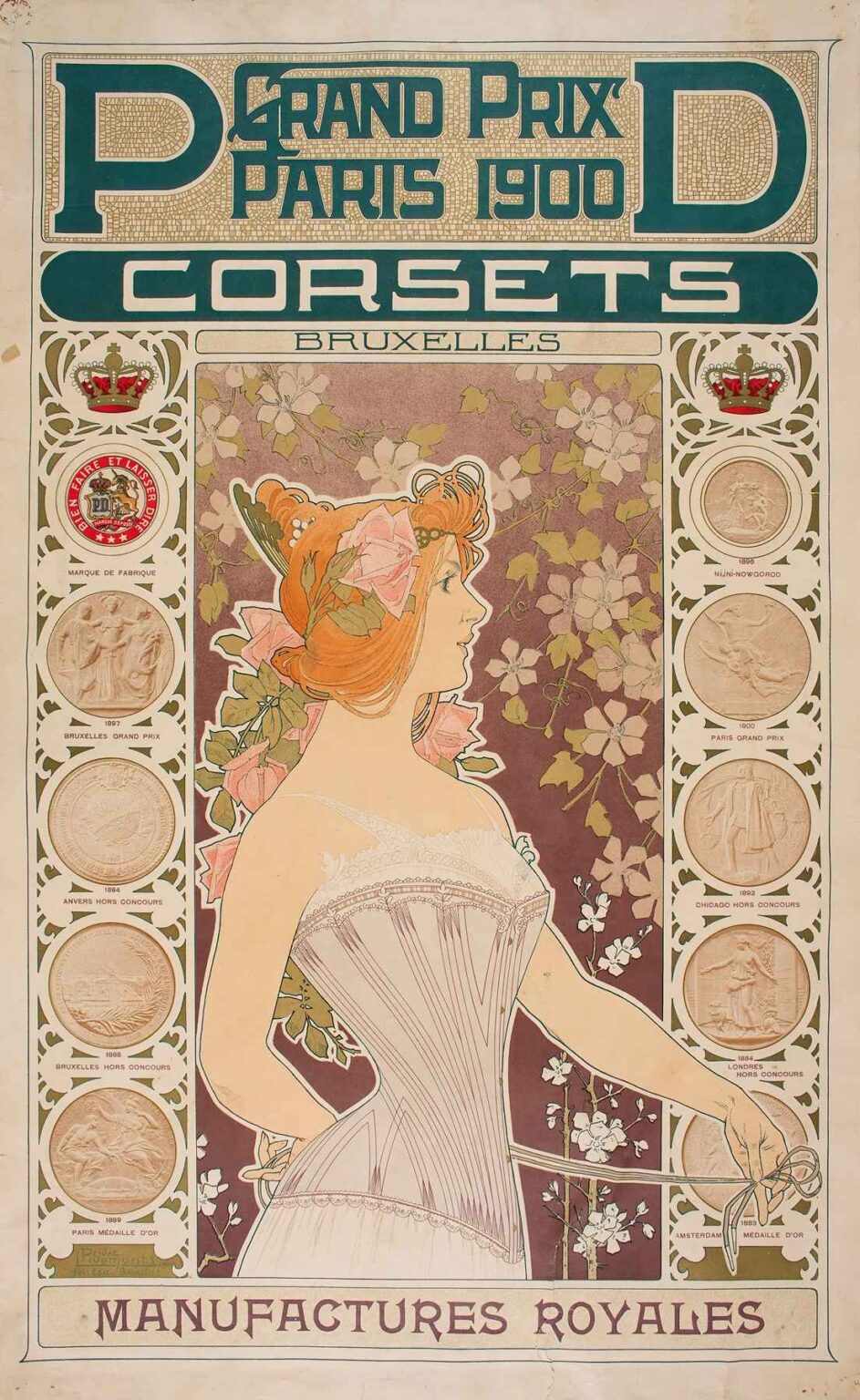

At the turn of the 20th century, the lines between fine art and commercial advertising blurred in fascinating ways. One of the most compelling examples of this convergence is Henri Privat-Livemont’s 1900 lithograph Pd Corsets, a decorative advertisement that exemplifies the height of the Art Nouveau movement. With its lavish stylization, flowing organic motifs, and a radiant female figure, the poster stands as both a product promotion and a cultural artifact that speaks volumes about fashion, femininity, and modernity during the Belle Époque era.

Henri Privat-Livemont, a Belgian artist often called the “Belgian Mucha,” specialized in posters that blended intricate linework with sensual imagery and floral motifs. While he created many striking pieces, Pd Corsets remains particularly resonant for its balance of aesthetic refinement and practical purpose. This analysis explores the formal, cultural, and symbolic dimensions of this iconic work.

Visual Composition: A Poster That Commands Attention

At first glance, Pd Corsets presents a stunning vertical format dominated by a statuesque woman in profile. The composition is symmetrical and ordered, a hallmark of effective poster design. Privat-Livemont constructs the image in three primary horizontal registers: the branding and accolades at the top, the central image of the corseted woman, and the product manufacturer at the bottom. These tiers guide the viewer’s eye in a logical flow from recognition to admiration to action.

What makes the image visually arresting is the controlled palette of soft creams, dusty pinks, sage greens, and deep violets—tones that communicate refinement rather than garishness. The Art Nouveau hallmark of integrating figure and background is clear here. The woman appears enmeshed in an environment of blooming morning glories, echoing the curves of her corseted waist.

The attention to line is meticulous: the sharp, vertical darts of the corset’s boning contrast with the flowing, curved contours of her body and the surrounding flora. These dualities—rigid versus organic, manufactured versus natural—speak to the tensions embedded in the product being advertised.

The Central Figure: Idealized Femininity and Erotic Suggestion

The woman in the poster is the embodiment of turn-of-the-century ideals of beauty. Her voluminous red hair is adorned with large pink flowers and pearls, blending human and botanical motifs in an erotic yet elegant fashion. Her body posture, slightly tilted with her arm curved behind, draws the viewer’s attention to her cinched waist and prominent bustline. While she is clothed in a corset, there’s an underlying sensuality in the presentation, heightened by the exposure of her shoulders and neck.

She is both subject and spectacle. Privat-Livemont does not present her as a real woman, but rather as an aestheticized archetype. She does not meet the viewer’s gaze; instead, she looks contemplatively into the distance, as though above and beyond ordinary concerns. This detachment reinforces her role as a symbolic figure—a muse, a fantasy, a dream of femininity sold to the public.

Yet she is also a consumer. The corset she wears is the product being promoted. In this duality, Privat-Livemont succeeds in turning the model herself into an advertisement. Her perfect form becomes both the justification and the result of the corset, and the poster subtly implies that such elegance and beauty could be within reach—if only one purchases the product.

Botanical Motifs: Nature Meets Commerce

Floral and botanical imagery was a cornerstone of Art Nouveau design, and Pd Corsets makes liberal use of this aesthetic. The morning glory vines behind the central figure are not just decorative; they are symbolic. Morning glories are often associated with beauty, renewal, and fleeting moments of splendor. Their use here suggests that beauty is both natural and ephemeral—a quality to be preserved and enhanced by wearing the right corset.

Furthermore, the flowers echo the curves of the female figure and the corset’s shape, blurring the lines between woman and nature. This visual strategy reinforces the idea that femininity itself is a kind of cultivated art, one best realized through stylish attire.

The floral background also works to soften the industrial nature of the product being advertised. Corsets are, at their core, engineered garments—made with steel, cotton, lace, and bone. But Privat-Livemont frames the corset within a garden of organic elegance, masking the mechanical reality with romantic flourish.

Typography and Decorative Accolades: A Message of Prestige

The top portion of the poster is dominated by bold typography: “GRAND PRIX PARIS 1900” declares the corset’s award-winning status. This emphasis on medals and accolades is repeated on both sides of the image, where a series of gold-toned medallions are displayed. These reference honors from various world fairs and exhibitions: Paris, Brussels, Chicago, London, Amsterdam, and more.

By prominently displaying these achievements, the poster links the product to international recognition and superior craftsmanship. It’s a strategy of persuasion, appealing to consumers’ desires for both beauty and quality assurance. The use of stylized, elegant fonts further enhances the tone of sophistication and refinement.

The crowned emblems flanking the central image elevate the brand’s status even further, implying that these corsets are worthy of royalty. The underlying message is clear: this is not just undergarment fashion—it is a matter of social stature and prestige.

Art Nouveau Ideals: Form and Function United

Henri Privat-Livemont was working at the peak of Art Nouveau’s influence in Europe. This movement was deeply invested in uniting decorative art with everyday objects, seeking to make beauty accessible through everything from architecture and furniture to advertising.

Pd Corsets is a textbook example of this ethos. It takes a commercial product—a corset, manufactured and sold en masse—and transforms its marketing into a work of art. Every element of the poster serves both a visual and rhetorical purpose. The flowing lines, sinuous forms, and natural imagery all communicate the underlying values of harmony, elegance, and stylized femininity.

Privat-Livemont’s work thus transcends mere advertising. It is both promotional and painterly. It reveals how even the most utilitarian of products can be embedded with symbolism and artistic intentionality.

The Corset Itself: Symbol of Constraint and Control

A deeper reading of Pd Corsets must contend with the object at its center—the corset. By 1900, corsets were standard in women’s fashion, but they were also increasingly controversial. While many viewed them as necessary supports for posture and fashion, others criticized them as instruments of bodily constraint and gender control.

Privat-Livemont does not explicitly address this controversy, but his image subtly reinforces the beauty of the corseted form. The woman’s waist is impossibly narrow, her figure a smooth hourglass shape. This idealized body is not achieved through nature alone; it is constructed, molded, and shaped by the garment.

In this sense, the corset becomes a symbol of transformation. It takes the raw material of the female body and sculpts it into a work of social acceptability and visual perfection. But this also raises questions: At what cost is this perfection achieved? Does beauty require pain, restriction, and artifice?

The poster does not answer these questions, but it invites contemplation—perhaps unintentionally—about the relationships between beauty, conformity, and freedom.

Gender, Desire, and the Male Gaze

Though targeted at women, Pd Corsets is clearly designed to appeal to men as well. The central figure is sensual, adorned, and idealized. Her posture is graceful yet suggestive. This layering of erotic appeal over a consumer product reveals the intertwined nature of advertising, gender norms, and the male gaze.

The woman is not just modeling the corset; she is made into an object of desire. This duality is what gives the poster both its allure and its underlying tension. It markets not only a product but a fantasy—one in which the buyer can participate by purchasing the corset.

This objectification, while common in turn-of-the-century advertising, becomes more complex when viewed through an Art Nouveau lens. The woman is beautiful, yes, but also powerful. She is confident, self-possessed, and adorned in symbols of prestige. In a way, she subverts the gaze even as she fulfills it.

Legacy and Influence: Beyond the Commercial Sphere

Today, Pd Corsets is valued not just as a piece of advertising ephemera, but as a significant work of poster art. It is collected, studied, and exhibited in art museums, where its details are appreciated on aesthetic and historical grounds. Its legacy extends beyond its original purpose, revealing the rich intersection between beauty, design, and consumer culture at the dawn of the 20th century.

The poster has also influenced generations of graphic designers and typographers. Its integration of figure and type, balance of form and function, and use of ornamental framing remain models of visual clarity and elegance. It stands as a testament to how powerful visual language can be when wielded with intentionality.

Conclusion: A Masterpiece of Decorative Advertising

Henri Privat-Livemont’s Pd Corsets is more than a lithograph promoting a garment. It is a jewel of Art Nouveau craftsmanship, a cultural mirror reflecting the ideals and contradictions of its time. Through its celebration of beauty, its rich decorative language, and its seductive promise of transformation, the poster invites viewers into a world where fashion meets fantasy, and commerce becomes art.

It reminds us that even the most everyday objects—like a corset—can carry layers of meaning when framed through the right artistic lens. With its blend of elegance, symbolism, and sophistication, Pd Corsets remains one of the most iconic and thought-provoking commercial posters of the Belle Époque era.