Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Southern Light

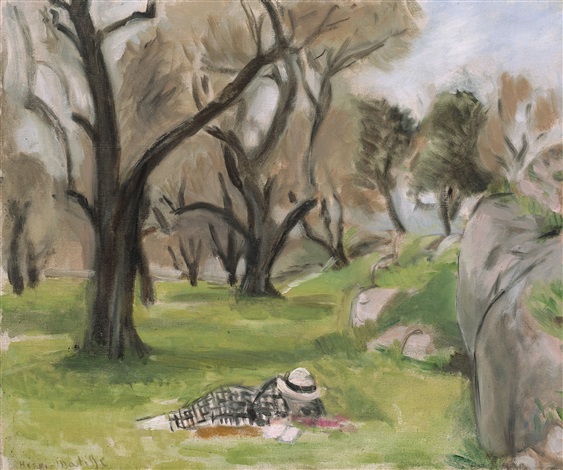

Henri Matisse painted “Paysage du Midi” in 1922, in the midst of his celebrated years working along the French Riviera. After the upheavals of the 1910s, he embraced the Mediterranean as both refuge and laboratory, a place where he could refine the essentials of painting—color relationships, rhythmic drawing, and the orchestration of light. The phrase “du Midi” signals more than geography; it evokes a way of seeing shaped by soft winters, silvery olives, and the lucid brightness of coastal air. This landscape carries the imprint of that light. It shows how, in his mature period, Matisse learned to let the environment determine the painting’s tempo. He did not impose a Fauvist blaze; he tuned a calm chord that suits the season and the place.

Composition As A Living Grove

The scene unfolds in a gently sloped grove whose trees fan upward like open hands. The composition is built from a low, ground-hugging foreground that rises to a belt of trees and then to a high, airy sky. The large tree on the left acts as a dark vertical anchor; from it, branching arcs carry the eye into the interior. A scattering of rocks at right forms a natural buttress, balancing the weight of the trees and preventing the composition from leaning. Near the center, a reclining figure in a patterned dress and hat rests on the grass. This figure is not an anecdotal protagonist but a measure of scale and a pulse of human presence within nature’s broader rhythm. Everything is arranged to encourage a slow, spiraling gaze: from the near grass to the figure, from there to the trees’ interlaced limbs, and finally up into the pale, breathing sky.

The Figure As A Lyrical Accent

Matisse’s interiors of these years often treat figures as nodes within an ornamental field; here the same logic applies to landscape. The supine figure does not break the serenity of the grove. Instead, the patterned dress echoes the mottled ground and the dappled light filtering through the leaves. The soft hat becomes a rounded interval between the vertical trunks. The posture—propped on elbows, perhaps reading—reinforces the painting’s mood of pause. Because the body is simplified and partially absorbed by the surrounding values, it functions less as a portrait than as a lyrical accent, a human breath exhaled into the clearing.

Palette And The Temperature Of Calm

The palette is tuned to olive green, pale sage, and warm gray, punctuated by the almost black brown of the trunks and the soft rose of exposed earth. The greens are not of summer’s saturation but of early spring or late winter, when new grass glows against still-sober foliage. The sky is a diluted blue-white that lets the darker tree tracery stand out without harsh contrast. By restricting the palette to a handful of related notes, Matisse creates a visual climate that suggests cool air warmed by sun. The rocks at the right, gently violet in their shadows, keep the harmony from sinking into monotony; their cooler notes refresh the eye and stabilize the field.

Brushwork And The Movement Of Air

The paint handling is loose and breathable. Across the grass, Matisse lays short, softly fused strokes that suggest blades without counting them. In the trees, he switches to more elastic lines whose slight tremor conveys sap rising and wind passing. The sky is scrubbed thinly enough that the ground tone pulses through, giving the light a felt temperature rather than a literal brightness. The overall touch is brisk but unforced. Nothing is overworked; nothing is diagrammed. The result is an atmosphere that feels in motion even as the composition remains poised. One senses the faint sound of leaves and the warmth of a patch of sun on the figure’s back.

The Midi Grove As Architecture

Matisse often conceived landscapes as rooms without roofs. Here the grove reads like a nave defined by tree-columns and branching ribs. The arcs of the limbs generate a vaulted canopy. The rocks act as side chapels. The green floor is a patterned carpet of shadow and sun. This architectural analogy clarifies why the reclining figure feels so at home: the grove is a built space, not constructed by human hands but composed by repeated organic elements. Matisse’s eye for pattern recognizes this order and amplifies it with his drawing, creating an architecture of living lines that supports the picture’s calm.

Drawing As Calligraphy Of Trunks And Limbs

The drawing is emphatic where it needs to be and tentative where it serves the air. The tree trunks are described with dark, undulant contours that thicken and thin like calligraphy. Branches fork with swift decisions rather than botanical enumeration. The outline of the rocks is softened at points of contact with grass, allowing forms to breathe into one another. The figure’s contour is light, as if sun and shadow were drawing it in tandem. This combination of firm and soft edges organizes the space without hardening it. The world remains porous, just as it feels when we lie in a grove and look.

Light As A Gentle Sieve

The light here is sifted through leaf and thin cloud. Rather than stage hard sun-shadow binaries, Matisse threads half-tones across the ground and trees. The green planes are mottled by subtle temperature shifts: slightly warmer where the sun lands, slightly cooler where the canopy thickens. The trunks wear a gloss of gray that hints at the silvery bark of olive trees. The distant foliage dissolves into a veil, reminding us that light increases with distance. By refusing theatrical chiaroscuro, Matisse builds a world where seeing is continuous, where every area participates in the same soft illumination.

Space Constructed By Overlap And Tonal Steps

Conventional perspective plays a minor role; depth arises from overlapping silhouettes and tonal steps. The nearest tree overlaps the middle group, which overlaps the far mist of trunks, creating a measured recession. The rocks at right turn with gentle value shifts rather than hard edges, so that the viewer senses their roundness without counting planes. The figure’s patterned dress sits in front of a cooler green patch, gaining legibility by contrast alone. This is mature Matisse: space made legible by relationships rather than by rules.

The Ethics Of Leisure

The reclining figure embodies a kind of leisure that is earned by attention. There is no picnic basket, no animated conversation, no narrative cue. The leisure here is the permission to rest in the world’s patterns. Matisse dignifies that pause by giving it a precise setting—the interlaced branches, the soft rocks, the half-grown grass—and by placing the body in quiet rapport with those elements. The painting’s ethic is clear: looking is a form of rest, and rest clarifies looking.

The Southern Landscape And Its Genealogy

Painters across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries sought the Midi for its air and trees, from Cézanne’s stern pines to Renoir’s warm orchards. Matisse’s grove shares their love of durable forms, yet his approach is more musical than geological. The rocks are not weighty symphonies; they are soft drumbeats. The trees are not volumes to be carved but lines to be sung. Where Seurat turned Mediterranean light into luminous systems of dots and Cézanne faceted it into planes, Matisse lets the light loosen the hand until drawing moves at the speed of a breeze.

Pattern And Nature In Equilibrium

Even in landscape, Matisse’s lifelong interest in pattern persists. The grass is a field of repeating marks; the branches repeat their bifurcations; the rocks repeat their rounded volumes. Yet pattern never hardens into design. Each repetition admits variation, as in music. Marks are similar but not identical, spacing is regular but not mechanical. The equilibrium between recurrence and difference is what keeps the scene alive. The viewer senses order without feeling trapped by it.

The Role Of The Right-Hand Rocks

The boulders at the right carry more than descriptive weight. They steady the composition by countering the left tree’s dark mass. They push gently back against the figure, preventing the central area from dissolving. Chromatically, their cool violet-gray refreshes the warm greens and ties the foreground to the distant haze. Their rounded shapes—echoed faintly by small mounds in the distance—also suggest a human place, a patch where one might sit, lean, or read. The rocks give the grove a tactile invitation.

Time Of Year And The Breathing Of Trees

The trees’ foliage appears thin, the branches legible through a veil of leaves. This suggests early spring, when the canopy has not yet thickened into summer shade. The season matters because it lets the sky participate. In midsummer, the grove might close; here it remains an airy structure. The painting feels timed to those first days when the earth is soft, the air mildly cool, and the sun low enough to rim objects without bleaching them. Matisse captures that breathing interval by refusing extremes of light or color, preferring moderated, truthful tones.

Relationship To The Nice Interiors

Although “Paysage du Midi” is an outdoor scene, its logic mirrors the interiors Matisse was painting around the same time. There is a structuring framework—in interiors a lattice floor or patterned wall, here a web of branches. There is a threshold—in interiors the open window, here the pale sky that enters between limbs. There is a figure integrated into pattern—odalisques among fabrics indoors, a reader among grasses outdoors. Understanding these parallels enriches the painting: it is less a diversion from his interior project than another chapter in the same book about how living forms and patterned fields can harmonize.

The Viewer’s Path Through The Grove

The painting offers a precise itinerary. The eye enters at the luminous patch of grass near the lower center, finds the reclining figure, and then climbs the nearest trunk. From there it wanders through a network of branches, hops to the right-hand rocks, and returns down the slope to the foreground. This circuit repeats at a slower pace, each lap revealing a new variance in the brushwork or a small, cooler pocket of shadow. The painting thereby becomes an instrument for looking that slows time without stopping it.

The Intelligence Of Omission And The Power Of Suggestion

Close inspection reveals just how much Matisse omits. There are no leaf-by-leaf descriptions, no detailed shadows of twigs, no botanical specifics of species. The figure’s face is barely notated. Yet the scene convinces through cumulative suggestion. A grayed green next to a warmer one gives the sensation of dapple. A single dark swivel at the base of a trunk hints at exposed root. Two lavender strokes on a rock imply both roundness and a cool plane. The power lies in the right omissions, which keep the image light enough to breathe.

Emotional Weather And The Poise Of Rest

The emotional tone is restful without languor. The trees’ reach gives the scene aspiration, the rocks offer steadiness, and the figure introduces tenderness. Nothing is melancholy; nothing is loud. The feeling is of a day when work pauses and attention widens. Many viewers report an after-image of quiet energy—precisely the state in which Matisse sought to place his audience, ready to perceive the world’s patterns with renewed patience.

Legacy And Contemporary Resonance

“Paysage du Midi” continues to resonate because it models a sustainable pleasure. In a visual culture of intensities, it proposes gentleness. It shows how a small range of colors, applied with conviction, can produce an ample world; how a figure can inhabit nature without dominating it; and how drawing can move freely yet remain exact. For painters and designers, the canvas teaches how to balance big masses against small incidents, how to coordinate cool and warm within one key, and how to allow edges to soften where air must circulate. For general viewers, it offers an invitation to step into a grove and to count rest as a form of knowledge.

Conclusion: A Grove That Breathes

“Paysage du Midi” distills Matisse’s mature vision into a modest, generous scene. A few trees, a few rocks, a reclining figure, and a carpet of grass become a complete world through calibrated color, calligraphic drawing, and a light that acts like a gentle sieve. The grove is not merely depicted; it is orchestrated, its rhythms tuned to the breath of the person resting within it and to the breath of the viewer who follows the brush across the canvas. In this landscape, Matisse proves once more that clarity is not the enemy of feeling. Clarity is the way feeling lasts.