Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

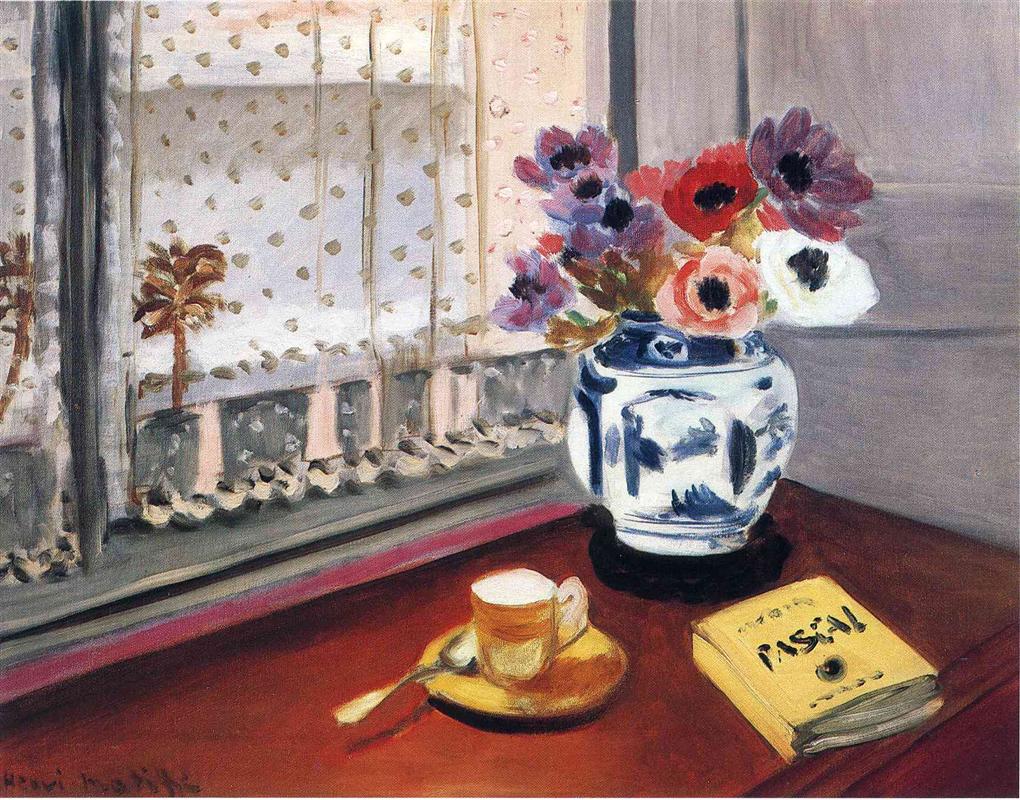

Henri Matisse’s “Pascal’s Pensées” (1924) is a poised interior in which the quiet rituals of thinking—reading, looking, tasting—become the true subject. On a polished table beside a shuttered window, a yellow book bearing Blaise Pascal’s title rests near a small espresso cup and saucer; a porcelain vase of anemones glows in the soft light; a lace curtain sifts the view of palm trees and pale sky beyond. Nothing here clamors for drama, yet the scene hums with attention. Matisse organizes color, pattern, and light so deliberately that the simplest objects—book, cup, flowers—share the same wavelength. The painting is not an anecdote about a particular morning; it is a climate of thought, a sustained chord where looking is as concentrated as reading.

Historical Context and the Nice Period Setting

By 1924 Matisse had long since turned from the volcanic contrasts of Fauvism to the luminous poise of his Nice period. He rented sunlit apartments on the Riviera and used them as laboratories for a modern classicism: ambient Mediterranean light, shallow layered space, and pattern used as architecture. Interiors with open windows allowed him to braid indoor still life with outdoor brightness, creating pictures in which air seems to circulate. “Pascal’s Pensées” sits squarely within this vocabulary. It is a cousin to the book-and-compote still lifes of the same years and to the window scenes with striped awnings. Yet the explicit naming of Pascal signals a slightly different emphasis: the room is tuned not only for pleasure but for attention, the kind that lets thought take hold.

Composition as a Study in Balance

Matisse builds the composition from three interlocking rectangles—the window, the shuttered wall, and the tabletop—then populates them with a triangle of objects whose weights are perfectly judged. At the right, the porcelain vase of anemones sits on a small round stand; its swelling body and sprightly bouquet form the apex of the triangle. In the lower center, the cup and saucer slip forward like a pause between thoughts. At the left, the yellow volume of “Pensées” leans toward the viewer, its cover lettered in assertive black. The window frame introduces a strong vertical and horizontal scaffold, while the lace curtain lowers a veil that clarifies rather than obscures. Each element is placed to control tempo: the book anchors, the cup slows, the flowers rise, the curtain drifts.

Pattern as Architecture

Pattern in Matisse’s interiors is structural, not cosmetic, and here it quietly does the work of perspective. The lace curtain is a field of small, regular dots that turn the window into a soft screen; because those dots repeat at even intervals, they flatten the view to the plane, preventing distant palm trees and sky from tunneling away. The porcelain vase carries a second kind of pattern—deep cobalt reserves on milky glaze—whose bold yet economical marks echo the curtain’s dots at a larger scale. Even the tabletop bears a narrow ribbon of rose along the edge, a small linear motif that keeps the polished wood from behaving like a blank void. Pattern paces the eye and holds the room together without recourse to heavy modeling.

Color Climate: Cool Poise with Warm Accents

The color climate is one of cool poise warmed by selected accents. The window registers in pale grays and soft sky tones; the shutter is gray-lavender; the porcelain is milk white tempered by blue. Against this cool field Matisse places three warm notes. The first is the bouquet: anemones in red, rose, violet, and white with dark centers, their petals touched by Mediterranean light. The second is the book, a yellow chord that catches and holds attention without shouting. The third is the cup and saucer, which carry a honeyed ochre and a gentle halo of reflected light on the polished table. These warm elements converse across the picture, and because no dead black is used—only chromatic darks—the exchanges remain breathable and musical rather than stark.

Light Without Theatrics

Matisse’s Nice-period illumination is ambient and benevolent. There is no spotlight carving sharp shadows across the book or vase; instead, light arrives as a general wash from the window, pooling on the table and glazing the porcelain with slow, milky highlights. The lace curtain does critical work here. It diffuses the brightness into a readable value scale while retaining enough clarity to let the outside world register: a palm beyond the sill, pale sea or sky, a faint ledge carrying potted plants. The soft, even light allows color to carry mood, and it allows the eye to travel without being ambushed by glare.

The Vase of Anemones: A Cloud of Living Color

The bouquet is painted with an economy that keeps it lively. Petals are wide, loaded strokes that flare and subside; dark centers are compact disks that hold the fluttering color in place; leaves emerge in swift, green thrusts that help bridge porcelain to bloom. The vase itself is a masterclass in restrained description. Its blue reserves are painted broadly yet precisely, aware of curvature without pedantry. A few cool reflections—gray-violet on the shoulder, a condensed gleam along the lip—are enough to state material. The black round stand grounds the vessel, deepening the tonal register near the table’s surface so the bouquet can rise.

The Book as Modern Emblem

The yellow volume of Pascal’s “Pensées” introduces the world of ideas into the still life. The cover is readable—big black letters against a cadmium ground—yet Matisse resists turning it into typography. The title is tilted, shaped by the pressure and speed of the brush. What matters is not legibility per se but the presence of a modern emblem within a classical arrangement. “Pensées” means “thoughts,” aphorisms wrestled from experience and belief. Placing that word inside a room of flowers, porcelain, and a cup of coffee proposes a humane synthesis: thinking as part of daily life, as proximate to beauty and savor as to silent study. The book’s color is also a structural note, a warm counterweight to the cool window and porcelain.

The Cup and Saucer: Pause and Intimacy

At the picture’s center sits the smallest object, a cup and saucer painted in warm ochres and creams, with a modest spoon glinting alongside. It is an emblem of pause, the brief interval in a morning of reading. The cup’s highlight is soft, a milky cap; the saucer’s rim catches a line of brightness; a faint ochre reflection pools on the tabletop beneath. These details bring the viewer physically close. We sense the table’s varnish, the weight of the porcelain, the suggestion of steam. Without the cup the still life might risk coldness; with it, the room gains a human pulse.

Space by Layers, Not Vanishing Points

Depth is achieved by stacking and overlap rather than linear perspective tricks. The tabletop forms the near plane, its edge running diagonally to the window. Middle space is occupied by cup, book, and vase. Rear space is the shutter and the curtained view beyond. The intervals between layers are short; the view is compressed, keeping the viewer at the table rather than thrusting them into an exterior. The lace curtain’s dot field flattens distance into pattern, maintaining modern surface truth while leaving enough hints for a believable world. This layered construction is part of why the painting feels restful: it avoids the anxious pull of vanishing points.

Drawing with Planes and Elastic Lines

Matisse’s draftsmanship is laconic and exact. The window mullions are slightly elastic, drawn with human pressure, not ruler-straight. The book is a block defined by a few edges, its thickness expressed by a single shadowed plane. The cup’s ellipse is a swift loop; the spoon is a quick silver stroke. On the vase, blue reserves are placed with calligraphic assurance, describing volume with minimal means. Everywhere, the drawing stops at the moment the form can stand. This economy leaves room for color to speak and for air to circulate.

Rhythm and the Music of Looking

The painting is paced like chamber music. Long notes are the window frame, the shutter panel, and the table plane. Middle beats are the vase’s oviform bulk, the book’s rectangle, and the lace curtain’s regular dotting. Quick notes sparkle as the spoon’s glint, the cup’s highlight, and the dark flower centers. The eye moves in a phrase: begin at the yellow book, climb to the cup, rise into the bouquet, drift through the lace into the pale exterior, and return along the window edge to the porcelain shoulder before sinking back to the table’s rose-tinted edge. Each circuit clarifies how warm and cool swap roles, how pattern steadies and color sings.

Touch and Material Presence

The surface of “Pascal’s Pensées” remains palpably handmade. The lace is a veil of tiny, pressed touches; the table’s sheen is a scumbled glaze that leaves the weave of the canvas breathing; the blue reserves on the vase are slightly raised pools that catch light along their edges; the book’s cover is a dense cadmium layer pushed to a clean edge; the shutter is a thin, brushed plane, its gray changing subtly as the arm slows or speeds. This variability of pressure and paint weight keeps the painting from becoming a mere diagram of ideas. It insists on the sensuous fact of painting even as the canvas pays homage to thought.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

The picture converses with other Nice-period works. Its window-and-lace motif echoes interiors like “Vase of Flowers,” where the sea’s cool band breathes through a room of warm surfaces. Its book on the table recalls “Still Life, ‘Histoires Juives’” and “Still Life with Apples on a Pink Tablecloth,” where rectangles of text counterpoint rounded fruit and vessels. But “Pascal’s Pensées” is pared down, almost austere in its selection of objects, so that the theme of cultivation—beauty allied with thinking—can be felt without redundancy. In this, it also nods backward to the philosophical quiet of “The Red Studio,” transposed here into a domestic scale and a cooler key.

Meaning Through Design

What does the painting propose? That a room can be tuned for attention. A curtain filters glare; a window holds a measured square of sky; a table carries objects that invite the mind to concentrate—flowers for vitality, a cup for pause, a book for inquiry. Nothing dominates; each part contributes to equilibrium. The presence of Pascal, a writer of bracing, compact meditations, is no accident. Matisse’s own method in Nice is Pascalian in discipline: state only what is necessary; rely on clear relations; let the whole be more lucid than the parts. The painting is therefore both homage and analog: a visual “pensée” crafted from color and light.

How to Look, Slowly

Enter by the yellow book and sound its warm note. Step to the cup and saucer and feel the soft highlight, the suggestion of heat. Rise into the bouquet and count the dark centers as if they were beats in a bar. Move through the lace’s dotted rhythm and let the exterior cool your eyes; notice the palm’s simplified silhouette and the pale band of sky. Return along the window frame to the porcelain, trace a single blue reserve as it curves, and drop back to the table’s rose edge. Repeat the circuit. With each pass the relations will clarify—the book warmed by the cup, the cup steadied by the vase, the vase cooled by the window, the whole held by the lace’s patterned light.

Conclusion

“Pascal’s Pensées” is a crystalline statement of Matisse’s Nice-period ethic. It turns a tabletop and a window into a complete world where color, pattern, and light are organized for the sake of attention. The book is not an intrusion of literature into painting; it is the emblem of what the room already embodies: concentrated seeing. Flowers offer vitality without noise; porcelain embodies form without fuss; a cup permits pause; a curtain sifts light. The painting’s serenity is not passivity but precision—a poise that remains persuasive because it shows how everyday objects, tuned with care, can host both thought and pleasure.