Image source: wikiart.org

First Look: A River, A Bridge, and a Row of Plane Trees

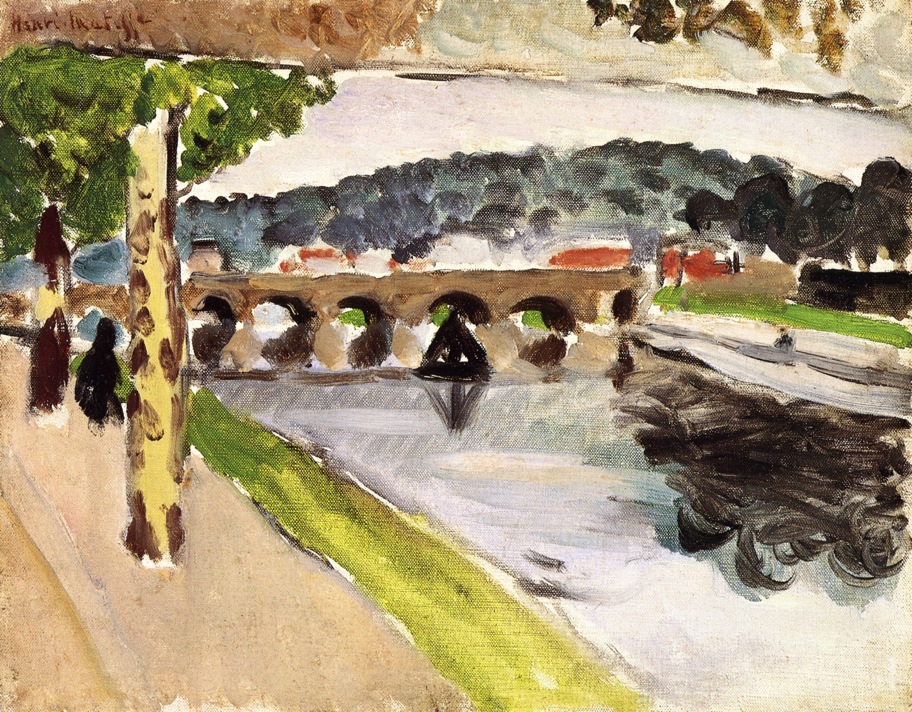

Henri Matisse’s “Parade, Platanes” (1917) compresses a riverside experience into a swift, lucid orchestration of shapes and strokes. At the left edge a mottled plane tree rises like a column. Beyond it a paved promenade recedes into the distance, shadowed by more trees and a few passing silhouettes. Across the water a low, multi-arched stone bridge slices the middle register, its arcades echoed by reflections in the river. A triangular river marker anchors the center, and a sloping green bank, bright as a banner, pulls the eye diagonally from foreground to distance. The sky is a pale, wind-rubbed gray; the water flashes with whites and smoky blacks. The painting feels immediate, as if the artist had stepped outside with a small canvas, found a position against the first tree, and recorded a living scene in a single, connected breath.

What the Title Tells Us

The title names two facts: a “parade” and “platanes,” the French plane trees whose camouflage bark and sturdy trunks are common on European promenades. “Parade” here is closer to promenade than procession—an amble rather than a spectacle. Matisse anchors the painting’s left margin with a close-view trunk and then lets the line of trees march outward. This avenue of platanes confers rhythm and civic order; it also acts as a theatrical proscenium, framing the river and the architecture beyond. The bridge’s repeated arches answer the trees’ cadence, turning the whole composition into a dialogue between natural and built rhythms.

The Composition as a Set of Coordinated Moves

Matisse organizes the picture through a few decisive axes. A vertical thrust is established by the foreground plane tree, whose bark alternates creamy yellow with brown patches. Opposing that vertical is a long, clean diagonal: the luminous green of the near bank sweeps from lower left toward the bridge. Across the middle third the horizontal run of the bridge stabilizes the design, and at the center the black triangular marker fixes the eye before releasing it to the right, where dark eddies of water curl against the quay. This network of vertical, diagonal, and horizontal motions allows him to keep the paint loose while the scene remains legible at a glance.

Palette and Atmosphere: Wartime Restraint, Lively Touch

The year 1917 brought a disciplined palette to Matisse’s work. Here he favors greens tempered by ochres and earths, a silvery gray sky, and passages of unmodulated black that provide both drawing and weight. Color is not flamboyant; it breathes. The emerald bank is the brightest note, but even that green is softened by quick additions of yellow and white. Buildings across the river appear as abbreviated red and ochre blocks. The water alternates between cool whites and smoky blacks, creating a quicksilver, slightly windy surface. The overall effect is sober without being dull, a climate appropriate to the period yet alive with hand and air.

The Plane Tree: Column, Curtain, and Measure

Lean close to the left margin and the plane tree reveals its function as both motif and measuring stick. Its mottled bark—painted with dabs that read as flakes—declares the closeness of the observer. The trunk becomes a curtain that one looks past, a convention painters have used since the Renaissance to create spatial drama. It also sets the scale for everything else: the width of the walkway, the height of the bridge, the depth of the river. By pushing the trunk right against the edge, Matisse asserts the plane of the canvas while simultaneously opening a view beyond it.

Drawing with Black: Structure Without Chiaroscuro

One of Matisse’s wartime discoveries was the use of black as a structural color. In “Parade, Platanes” black defines rather than shadows: it draws the bridge’s arcades in brisk, oval strokes; it establishes the river marker with a single triangular wedge; it darkens the right bank into a mass that both contains and contrasts the river’s light. Because this black is applied openly, with visible bristle marks, it acts like carpentry for the picture. It holds the large, quickly brushed fields of green, beige, and gray in a stable relation, allowing the artist to keep modeling to a minimum.

Brushwork You Can Read From Across the Room

The painting wears its making on the surface. The sky is laid down in lateral sweeps that leave a faint grain; the river is a set of broader strokes, some loaded and opaque, others scumbled thinly so the weave of the canvas peeks through; the bridge’s arches are abbreviated with circular, almost calligraphic turns of the wrist. On the promenade, dark silhouettes of walkers are resolved in two or three touches. This economy doesn’t impoverish the view; it liberates it. The eye completes what the hand only suggests, so the scene stays mobile, as if a breeze could lift it.

Space Built From Overlap and Tempo

Rather than relying on linear perspective, Matisse constructs space by overlap and by the tempo of marks. The tree cuts in front of the promenade; the promenade leads behind the tree into a band of mid-value gray; the bridge occludes the far bank and is itself interrupted by the arches’ shadows; the river flows under and past everything. Because each register carries a slightly different stroke-speed—slow, long passes in the river, quicker dabs in the foliage, firm horizontals in the bridge—the eye experiences distance as a change in rhythm as much as a recession in depth.

The Bridge: Architecture As Rhythm

The stone bridge occupies the picture’s center like a measured phrase. Its low arches repeat across the canvas, each punched through with a dark oval and topped with a slab of warm beige. Rare small touches—streaks of white catching on the bridge’s crown—suggest sun and texture without pedantry. The repeating arches rhyme with the ranked trees and, by extension, with the undulations of the water’s surface. You feel a city’s order insinuating itself into a natural course, yet the painter’s handling keeps the order from becoming mechanical.

The Triangular Marker: A Small Shape With Big Work

At dead center sits a dark triangular marker—possibly a navigation beacon—planted in the river like a pointer. Its job is compositional before it is nautical. It concentrates the river’s broad movement into a crisp sign and marks the literal midpoint where banks, bridge, and water cross. It is the picture’s only simple, unmodulated black shape, and by being so it calibrates the rest: the blacks in the right-bank eddies, the arch-shadows, the silhouettes on the promenade. Without that triangle the painting would breathe; with it the painting both breathes and speaks.

The River’s Surface: Light As a Pattern of Decisions

Water is the most abstract element here, and Matisse accepts that challenge. He does not try to mirror the world in the river; he builds a surface state. Pale passages register the open sky; darker scrolls on the right indicate currents catching on the quay; little horizontal dashes indicate ripples under a breeze. The paint remains frank: strokes are left to speak as strokes. Yet the total reads as water because the painter has tuned value and direction carefully. The river becomes a record of touch that is also a believable body of water.

People at the Edge: Life Without Anecdote

On the left walkway two small figures drift beneath the plane trees. They are not individualized; each is a vertical note in a row of uprights. Their presence matters less as narrative than as scale and tempo. They slow the eye just enough to suggest an ordinary day, a public place where people move along a tree-lined path while traffic (boats or current) passes under the bridge. Matisse rarely lets these staffage figures become protagonists. He offers human presence without handing the painting over to anecdote.

The Canvas as a Participant

In several places the weave of the canvas remains visible because the paint is scrubbed thinly or left out entirely. This is not carelessness; it is part of the optical strategy. Where raw canvas breathes through the whites of the river or the sky, it cools the color and lightens the mood. Where impasto gathers—at the green bank’s crest or within the bark patches of the plane tree—the surface picks up real light and roughness, intensifying foreground presence. Material truth helps carry pictorial truth.

Between Fauvism and the Nice Years

“Parade, Platanes” sits at a hinge in Matisse’s development. From Fauvism it retains the belief that a painting can be built from large, emphatic color-shapes and that drawing can be an active, elastic line. From the Nice period to come it anticipates the love of promenades, screens, and the patterned theatre of daily life. Yet the picture belongs to its wartime moment in its restraint. The colors are tuned but not ecstatic; the drawing is economical; black is allowed to assert itself as a constructive force.

The Eye’s Path Through the Picture

Stand back and track how the scene conducts you. The mottled trunk grabs first, close and tactile. Your gaze slides along the bright green wedge of bank toward the bridge. You pause at the triangular marker, then cross through the middle arch into the smudged blues and greens of the far bank. The dark swirl on the right pulls you back along the water’s edge, where a small figure sits or pauses. Finally, the eye returns to the left, back up the trunk, and out through the canopy. The path is complete yet never closed, which is why the painting feels walkable.

The Ethics of Reduction

A great strength of this small canvas is its refusal to over-specify. Buildings are red and white blocks; the promenade is a pale ribbon; tree foliage is massed into cool greens and ochres. Such reduction is not an absence of care but a form of respect—for the viewer’s eye, for the speed of experience, for the breadth of a landscape seen in one sitting. Matisse paints just enough to propose how things sit in relation to one another. What remains unsaid leaves the picture open and fresh.

Lessons for Painters and Viewers

Painters can learn here how to orchestrate a complex scene with a handful of structural moves: an anchoring near object, a guiding diagonal, a stabilizing horizontal, and a small, emphatic centric sign. They can study how a disciplined palette still yields variety when values are carefully spaced and undertones allowed to show. Viewers can practice reading surface as meaning—seeing how the direction of a stroke, the status of a line, or the unpainted patch of canvas contributes concretely to the sensation of place.

Why “Parade, Platanes” Endures

The painting endures because it delivers a public space with the intimacy of a sketch and the authority of a design. One feels the ordinariness of a riverside walk and the lyric inevitability of the forms that make it coherent: trunk, bank, bridge, water. It is a picture of movement and pause, of a city that breathes under trees by a river, reduced to essentials and animated by touch. In a year when Europe was strained to the breaking point, Matisse offers not escape but clarity—a modest scene made luminous by exact relations.