Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

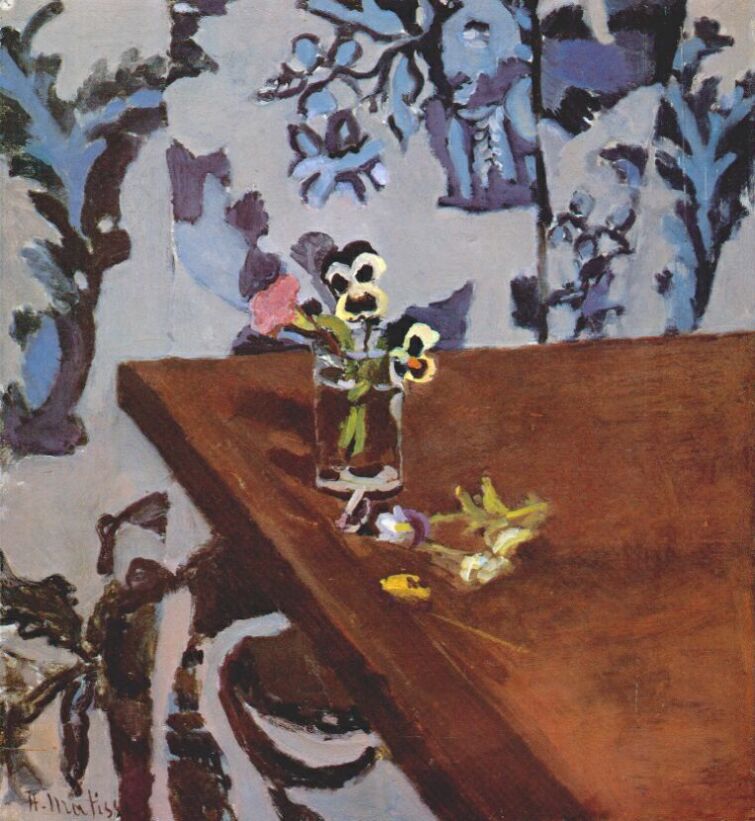

Henri Matisse’s “Pansies on a Table” (1919) is a masterclass in how little a painter needs to transform ordinary objects into a complete visual architecture. A few pansies in a simple drinking glass, a handful of fallen blossoms, a mahogany tabletop that sweeps in from the right as a bold diagonal, and a patterned wall or hanging that fills the background in smoky blues—these elements become a poised conversation of color, contour, rhythm, and light. Rather than staging abundance, Matisse chooses sparseness. The restraint is purposeful: with fewer distractions, every relation counts more. The glass catches just enough light to convince; the tiny yellow hearts of the pansies sound against cool, moonlit blues; the table’s plane is a single, decisive statement that organizes the scene. In this small still life, Matisse encapsulates the Nice-period program he launched after World War I: calm clarity built from measured color and decorative structure.

The Nice Period Context

By 1919 Matisse was working in Nice, rebuilding his art after a decade of upheaval in Europe and in his own experiments. He exchanged the blazing shocks of Fauvism for a quieter, steadier harmony rooted in interiors—rooms with screens, patterned fabrics, windows that open to sea light—and in compact still lifes that could be tuned like instruments. “Pansies on a Table” belongs to this phase. It rejects virtuoso detail and deep perspective in favor of shallow, breathable space; it leans on large planes and living contours; it treats pattern not as ornament pasted on top but as a structural participant. The painting’s domestic scale is integral to its ambition: Matisse proposes that a small tabletop can be a complete world if the relations within it are precise.

First Impressions

At first glance, the table dominates as an angled, auburn wedge, its warm plane sweeping from the right edge toward the left foreground. Perched near the table’s top edge sits a plain, cylindrical glass holding a few pansies—cream, purple, violet-black, and yellow—plus one pink flower that leans out like a whisper. Several blossoms and stems lie on the wood nearby, as if recently rearranged. Behind, an all-over pattern of indigo and bluish-lilac foliage climbs across a pale ground. The pattern’s broken silhouettes repeat the curving shapes of petals and leaves, so background and bouquet quietly rhyme. The whole scene is compressed against the surface; we are close enough to see the brevity of each brush touch.

Composition: Diagonal Stage, Patterned Backdrop

Matisse organizes the composition around a strong diagonal—the long edge of the table—which converts a simple still life into a dynamic stage. That slanted plane does three jobs at once. It introduces depth without hard perspective, it pulls the viewer’s gaze across the painting, and it sets up a counterpoint to the verticals and arabesques of the background. The little glass is placed just off the central axis so the diagonal doesn’t feel mechanical. The fallen flowers extend the line of the glass toward the viewer, knitting foreground and midground. Meanwhile the patterned wall (or curtain) functions like a theatrical backdrop. Its cool, intricate forms hold the surface while implying space, a signature Nice-period solution that lets the picture remain a designed object even as it suggests a room.

Color Architecture

The palette is deliberately limited and exquisitely tuned. The table is a deep, reddish brown with soft variations—warm sienna in the light, cooler umber in the shadow—so it reads as weight and warmth. The background is a veil of grays, lavenders, and midnight blues; these cools keep the room’s temperature humane and allow the flowers to register with clarity. The pansies supply the accents the harmony needs: small yellow hearts, creamy whites, soft violets, purple-blacks, and a single note of pink. Because the accents are tiny against broader fields, they ring like bells rather than shouting. Crucially, color families repeat across zones. The violet of the blossoms finds kinship in the background’s indigo; the warm table echoes faintly in the stems’ olive tints and in subtle brown notes within the pattern. This cross-referencing is why the image feels inevitable: nothing is isolated, everything participates.

Light and Atmosphere

Mediterranean light in Matisse’s Nice interiors is even and considerate. Here, illumination comes from above-left, soft enough to avoid sharp cast shadows yet strong enough to spark a few key highlights: a glint along the rim and base of the glass, a pale lift on a petal, a faint sheen along the table edge. The background pattern remains matte, like painted plaster or printed fabric absorbing light. This quiet climate lets color work at a conversational volume. The glass reads as glass not by meticulous reflection but by two or three strokes that announce transparency and curvature. The modest light is part of the painting’s ethics: clarity without glare.

Drawing and the Living Edge

Contour is central to the painting’s lifelike presence. Matisse draws with the brush, not by enclosing forms in little fences but by letting edges thicken and thin according to pressure and purpose. The lip and bottom of the glass are written in a few confident loops; stems inside the water are indicated by quick green verticals that bend as water distorts them; the table edge is a broad, slanted band that softens where light diffuses. In the background, the patterned silhouettes are not sharply cut stencils; they are breathing shapes, their perimeters broken or feathered to avoid stasis. The fallen blossoms on the tabletop are especially telling: a quick, irregular oval for a floret, a chevron for a leaf, a darting stroke for a stem. Economy replaces description, and yet the things feel more true for that restraint.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The painting’s materials narrate themselves. The table is laid in with long, directional strokes whose slight transparency allows the ground to flicker through, mimicking the grain and sheen of polished wood without copying it. The background is knit from short, overlapping passes that leave a dry bristle at the margins, recalling the texture of painted fabric or faded wallpaper. The flowers are touched in with richer, creamier paint that lifts from the surface, so petals seem nearer to us than wall or table. The glass is an elegant paradox: the most solidly convincing object is also the most lightly painted—two or three translucent strokes suffice. Matisse’s touch converts paint into substance without resorting to illusionism.

Shallow Space, Deep Relations

There is little conventional perspective here. Depth is a matter of overlaps and tonal steps: table in front of wall, glass on table, fallen flowers between. Because space is kept shallow, the viewer pays attention to relations on the surface—how warm and cool negotiate, how line and plane alternate, how pattern echoes stem and petal. This is the modern still life Matisse perfected in Nice: less a window opening to a room than a designed field that convinces by coherence. The pansies are not islands; they are notes within a chord sounded by table and wall.

Pattern as Structure

The background is an all-over arabesque of leafy silhouettes in layered blues. Far from being “behind” the subject, this pattern organizes the painting. Its repeating curvilinear units balance the rectilinear thrust of the table. Its cool tonality counters the table’s warmth. Its rhythm resonates with the rounded heads of the pansies so that bouquet and wall feel like variations on a theme. This use of pattern as structural counterpoint is a hallmark of the Nice period. Screens, carpets, wallpapers, and printed cloths are not mere props; they are architecture. Here the pattern’s scale—much larger than the small blossoms—also performs a game of proportion that makes the tiny bouquet feel precious without sentimentality.

The Choice of Pansies

Why pansies? Matisse frequently used humble flowers—anemones, daisies, carnations—because they carried clear shapes and strong, simple color intervals. Pansies add another gift: the “face” of each bloom, with its dark mask and bright heart, acts like a self-contained composition within the larger painting. A single flower can deliver black, yellow, white, and violet in crisp adjacency. In a restrained palette such as this one, that little bundle of contrasts is priceless. Their scale and fragility also align with the painting’s ethic of intimacy. This is not a display bouquet; it is a few stems gathered, considered, and arranged so the room’s larger music can be heard.

Narrative Hints without Anecdote

Still lifes often tempt us to imagine stories. Here, the fallen flowers on the tabletop suggest recent handling. Perhaps an earlier, fuller cluster was edited to just a few stems; perhaps the blossoms were laid down so each color could be weighed against the background and table. But Matisse refuses to turn the suggestion into anecdote. The painting stays focused on visual relations. The “story” is the choreography of warm and cool, thick and thin, plane and pattern. In this way the work practices a kind of pictorial honesty: it tells us exactly what matters in its world.

A Path for the Eye

The painting offers a natural viewing route. The eye enters along the long edge of the table, rides its diagonal to the glass, pauses at the crisp yellow centers of the pansies, and hops among the petals’ alternating darks and lights. From there it slides to the fallen blossoms, circles their small constellation, and then lifts into the background pattern, tracing its arabesques as they expand across the wall. The loop returns to the glass, where the highlights at rim and base flash like quiet cymbals. Each lap reveals a new echo—how a dark petal mirrors a dark patch in the wallpaper, how a green stem inside the glass aligns with a blue vine outside it, how the table’s warm plane throws the cool background into relief.

Comparisons within Matisse’s 1919 Still Lifes

Seen alongside “Still Life with Lemons,” “Flowers,” and “Daisies” from the same year, “Pansies on a Table” appears the most ascetic. There is no extravagant vessel, only a humble glass; no crowded bouquet, only a few small faces; no theatrical light, only steady day. Yet the structural concerns are identical: a controlling plane (table, floor, or shutter), a patterned counter-field (wallpaper, textile), and a compact cluster of saturations to focus the harmony. This canvas proves how far Matisse could go with less—how a single diagonal and a handful of accents can carry a complete composition.

Dialogue with Tradition

Matisse’s still life belongs to a lineage that runs from Chardin’s modest table pieces through Manet’s audacious bouquets to Cézanne’s constructed apples and cloths. He inherits Chardin’s humility of subject and Cézanne’s devotion to relation over description, but he adds his own modern twist: the elevation of decorative pattern to the status of structure. In “Pansies on a Table,” the wall’s arabesque is as architecturally important as the table; both are coequal partners. The painting thus updates the genre for the twentieth century, showing how modern flatness and domestic intimacy can coexist.

Material Choices and Palette Notes

The surface suggests traditional oils handled with deliberation: lead white softens the background ground; ultramarine and cobalt mingle with touches of ivory black to build the blue pattern; earth reds and ochres create the table’s warmth; chromium oxide or viridian mixed with yellow supplies the stems; alizarin and manganese violets shape petals; small strikes of cadmium yellow spark the flower hearts. Paint thickness varies with function: thicker for petals to bring them forward, thinner for wall to let air and canvas breath, mid-weight for the table so its plane reads firm.

How to Look Today

Begin by letting the diagonal table set your pace. Stand close to feel the grain of the brush, the way a single stroke makes a petal, the tender lift of paint at the glass rim. Step back until the pattern in the background hums as one field and the little panoply of pansies gathers into a single chord. Notice the limited palette and try to count the distinct colors; you’ll find far fewer than your first impression suggested. The satisfaction the painting provides is not from detail accumulated but from relations clarified. It rewards sustained attention the way a well-played chamber piece does—quietly, persuasively, durably.

Conclusion

“Pansies on a Table” distills the Nice period into a still life of uncommon poise. A strong diagonal establishes stage and depth; a patterned wall stabilizes the surface; a few small flowers, placed with care, provide color counterpoints that tune the whole. Brushwork remains visible; edges breathe; light is steady and humane. Nothing is decorative in the cheap sense; everything is decorative in the structural sense. Out of ordinary things Matisse builds a room where looking itself becomes the subject—a clear, restorative act that still feels modern a century later.