Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

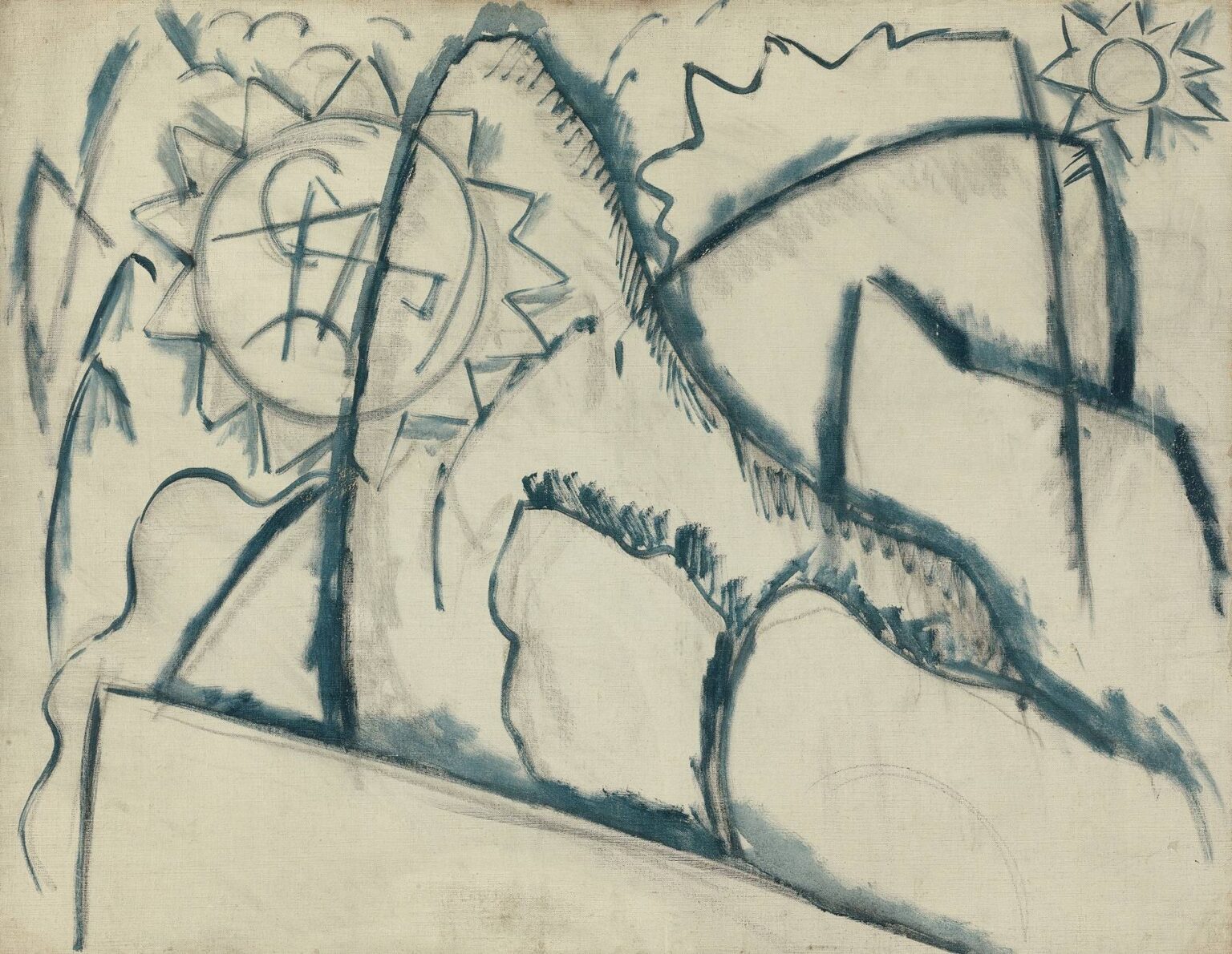

Marsden Hartley’s Painting No. 8 (1913) appears, at first glance, to be little more than a network of brisk blue lines racing across an untouched canvas ground. Yet this spare, calligraphic web is a decisive statement from an artist standing at the threshold of full abstraction. Created in Berlin during one of the most feverish moments of the European avant‑garde, the picture compresses symbol, rhythm, and structure into a skeletal score. Sunbursts, diagonals, looping arcs, and angled planes imply landscape and icon, instrument and banner, all while refusing to settle into a single decipherable scene. What looks unfinished is in fact a conscious exposure of process: Hartley lets the armature show, revealing how thought becomes form.

Berlin 1913 And The Urgency Of Experiment

Hartley arrived in Berlin in 1913 and encountered a city crackling with modernist energy—military parades clanged through the avenues, Expressionist painters debated spiritual abstraction, and Cubist innovations raced across studio walls. At the same time, he was shedding the vestiges of American Impressionism and the structural naturalism of Cézanne, searching for a language capable of holding private feeling and public spectacle. Painting No. 8 emerges from this crucible. By stripping color to a single blue‑black and paring form to contour, Hartley could think faster on the canvas, testing a personal syntax that would soon coalesce into his celebrated “German Officer” abstractions. The numeric title underscores the experimental mood: this is one in a sequence, a laboratory note rather than a genre label.

The Drama Of Line And The Refusal Of Mass

Line is everything in Painting No. 8. Thick and thin strokes surge, hesitate, and reverse, establishing a choreography that substitutes for volumetric modeling. Hartley draws as if with a reed pen dipped in indigo, letting the brush drag dryly in places and flood in others. Angled diagonals intersect with curving arcs, creating a tension between rigidity and flow. The absence of filled color makes every contour carry weight; each stroke must both describe and energize. The result is a drawing that behaves like painting—gestural, physical, insistent—while preserving the skeletal clarity of draftsmanship. In denying mass, Hartley invites viewers to experience structure as a living, provisional entity rather than a finished shell.

Compositional Framework And The Pulse Of Symmetry

Despite its apparent looseness, the composition is carefully balanced. A dominant diagonal slices upward from the lower left, meeting a counter‑diagonal that descends from the upper right, creating a tilted X of force lines. Within this framework Hartley nests two radiant discs, each ringed with jagged rays that read as suns or emblems. One hovers near the upper left, pierced by internal glyphs; the other, smaller and simpler, glows in the upper right corner like a distant echo. Between them stretches a ridge‑like form, saw‑toothed along the top, that evokes a mountain range or fortification. At the base, an angled plane—perhaps a parapet, perhaps a stage—grounds the flux above. The eye ricochets among these anchors, guided by repeated motifs and echoed angles that enact a visual rhythm, a kind of call and response in line.

Symbolic Hints: Suns, Sigils, And Unfinished Icons

Hartley’s abstraction rarely abandons meaning altogether; instead it buries references inside form. The starburst discs recall decorated military orders, Byzantine halos, or esoteric diagrams. Within the left disc, faint intersecting curves and bars suggest a cipher—a private monogram or a mystical sign. The serrated ridge could allude to mountains, recalling Hartley’s lifelong reverence for monumental landforms, or to serrated heraldic crowns seen atop standards. Even the snaking line at left might be a river, road, or serpent, a dynamic counter to the orthogonal elements. By presenting these forms in embryonic outline, Hartley preserves their ambiguity, allowing them to function as polyvalent signs—both personal and archetypal.

The Power Of The Bare Ground

The untouched canvas is not empty; it is an active field. Its warm, slightly irregular weave peeks through every stroke, softening the severity of the blue and lending the picture a breathlike openness. This negative space acts as silence in music, the pause that gives notes shape. It also foregrounds the physical fact of painting: we see pigment lying on fabric, thought meeting material in real time. In later works Hartley would often cover every inch with impasto. Here he trusts voids to do part of the work, letting absence mark presence, letting the viewer’s eye complete what the line only begins.

Gesture As Evidence Of Mind And Body

The varying pressure of Hartley’s brush betrays emotional states as much as compositional decisions. Some lines accelerate, then taper off, as if confidence gave way to reconsideration. Others thicken at turns, suggesting a pause and recommitment. Smudged passages reveal wiping or reworking, preservation of earlier attempts under the final contour. These material traces function like marginalia in a manuscript, clues to the artist’s thinking. In 1913, when Kandinsky and others argued for the spiritual power of abstract gesture, Hartley’s visible touch aligned with a belief that brushwork could transmit inner vibration directly to the viewer. The painting becomes not just an image but an event—a record of kinetic thought.

Between Drawing And Finished Work: Intention And Incompletion

Is Painting No. 8 a finished painting or a preparatory study? Hartley’s decision to exhibit and title it as a painting suggests the former. He elevates the draft to the status of artwork, challenging hierarchies that privileged polished surfaces. This choice participates in a broader modernist valorization of process—Rodin’s plasters, Picasso’s collages, Matisse’s cutouts—where the studio experiment becomes the final statement. By stopping where he did, Hartley forces attention onto his syntax rather than his polish. The viewer must grapple with line alone, encountering the nervous system of his art without the flesh of color.

Musical Analogies And The Notation Of Form

The canvas reads like a score. Repeated motifs—spiky sunbursts, scalloped ridges, looping arcs—function as themes that Hartley varies across the surface. The intervals between them create rhythm; the thickened strokes serve as accents. The diagonal “staff” lines on which these motifs sit recall musical staves, and the sigils within the large disc resemble notes or clefs. Hartley had long been drawn to the idea of synesthesia, of painting as a form of sound. Here, by limiting himself to line, he approaches literal notation, producing what might be called a visual aria of sharp and soft consonances.

Dialogue With Cubism And Expressionism

Hartley fuses Cubist structuring with Expressionist vigor. The segmented planes, angled scaffolds, and avoidance of perspectival depth nod to Cubism’s analytical breakdown of form. Yet the emotional force of the mark—the drive, the swell, the sweep—is pure Expressionism. Unlike Picasso’s cool investigations or Kandinsky’s color‑drunk rhapsodies, Hartley keeps a foot in both camps. He abstracts from the world but does not abandon its echoes; he emotes through line but orders that emotion with armatures learned from Paris and Munich. Painting No. 8 thus articulates a hybrid modernism, one that would become characteristic of American abstraction: intensely personal, structurally savvy, unwilling to choose between feeling and form.

The American Trace Inside A European Moment

Though forged in Berlin, the work carries Hartley’s Americanness. The hinted mountains and sunbursts anticipate the monumental landscapes of Maine and the Southwest that would later define him at home. The rawness of the exposed ground and the straightforward numbering speak to a Yankee plainness beneath cosmopolitan veneer. In retrospect, this drawing‑painting foreshadows the way many American modernists—Georgia O’Keeffe, Arthur Dove, John Marin—would blend European innovation with vernacular directness. Hartley is already translating rather than merely imitating, converting continental ideals into a dialect he could own.

Legacy Within Hartley’s Oeuvre And Beyond

The linear energy and symbolic shorthand of Painting No. 8 reverberate through Hartley’s subsequent decade. The circles morph into military medals, the zigzag ridges into epaulettes and mountains, the diagonal beams into banners and altars. Later, when color floods back in, the underlying drawing remains the scaffold. For later generations, the work anticipates the gestural drawing of Abstract Expressionists and the diagrammatic clarity of Minimalist notation. It proves that an American painter could approach pure abstraction not by evacuating meaning but by compressing it, reducing the lexicon to its charged bones.

Conclusion

Painting No. 8 is a manifesto written in strokes: swift, searching, and sure. By staging suns, sigils, ridges, and diagonals without filling their bodies, Hartley invites viewers into the crucible where symbol becomes structure. The blue line is thought made visible, a wandering yet purposeful path across the open field of canvas. In this spare language we sense the birthing of a voice—American, modern, spiritual, and fiercely individual—poised to explode into the color‑saturated icons of the years to come. Hartley shows that to abstract is not to erase, but to distill; not to finish less, but to reveal more.