Image source: wikiart.org

The Summer When Color Became Light

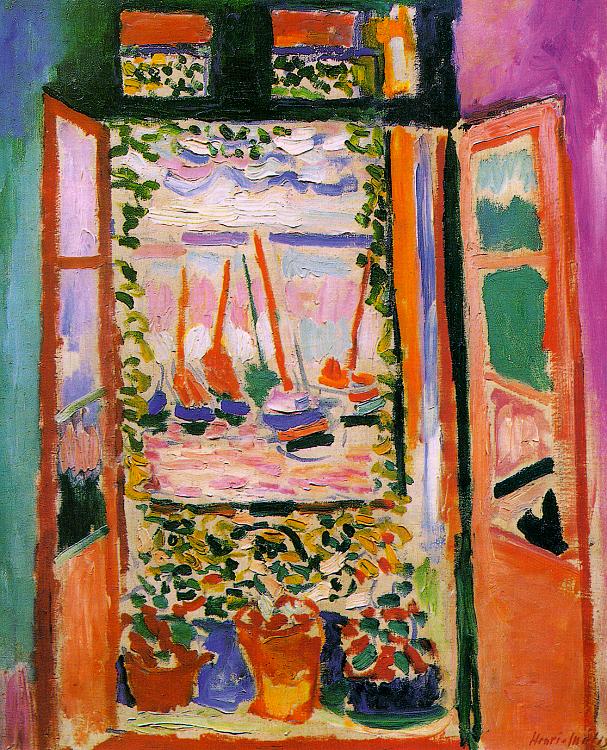

“Open Window, Collioure” was painted in 1905, during the blazing Mediterranean summer when Henri Matisse discovered a new pictorial grammar that critics would soon call Fauvism. In the small fishing town of Collioure, he set aside careful tonal modeling and the optical rules of Neo-Impressionism in favor of pure, high-key color placed with conviction. This canvas is among the clearest statements of that breakthrough. It shows a room flung open to the harbor, where boats float on pink water beneath a pearly sky, and where the frame of the window itself—sill, shutters, lintel—becomes a stage on which color and light perform. Rather than describing things with shadows and contour, Matisse lets complementary hues and breathing reserves of canvas generate form, space, and atmosphere.

First Impressions and the Motif

The picture presents a tall French window seen from inside. The shutters are thrown wide; pots of geraniums and other plants crowd the sill; a vine garlands the jambs; the sea and a line of masts rise just beyond. The view is both intimate and expansive. The room is close enough to touch—its woodwork reads as orange and black bars—while the harbor feels boundless, a band of lavender water beneath light-bathed air. Boats carry simple shards of color for hulls and sails. Nothing is fussy. With a handful of strokes, Matisse makes a coastal morning that seems to breathe warm air and salt.

Composition as a Proscenium for the Sea

The architecture of the window is not merely scenery; it is the engine of the composition. Two verticals—the dark interior jamb at right and the patterned, ivy-trimmed jamb at left—stand like theater wings. Across the top, a transom with small panes and snippets of vine functions as a shallow frieze. These strong edges frame a central rectangle of outdoor light in which the boats and water reside. The shutters open at slight angles, creating diagonal thrusts that guide the eye inward. The pots on the sill form a chorus across the lower edge, their rounded shapes softening the rigorous geometry above. The viewer’s gaze travels in a loop: up the left jamb, across the transom, down the right jamb, into the harbor, and back along the sill—an elegant promenade that transforms looking into motion.

Color as Architecture, Not Ornament

Warm–cool oppositions construct the scene with the clarity of masonry. The room’s edges are built from hot pigments—coral, orange, vermilion—stabilized by assertive black seams. The sea and sky are cool, rendered in ribbons of lilac, pale blue, and creamy white, with denser strokes of ultramarine standing for reflections and wavelets. The vine and potted plants supply saturated greens that lock into the reds and pinks as natural complements. Matisse does not “fill in” forms; he sets hues adjacent so that their meeting acts as a drawn line. A dark green arc against orange declares a shutter; a streak of lavender beside pink writes the far horizon. Because the temperature of each zone is clean, space reads instantly without the crutch of conventional shading.

Brushwork and the Physicality of Paint

The surface is exuberant with varied touches. In the water, short horizontal dabs accumulate like scales, thickening where color wants weight and thinning where glare demands breath. In the foliage, curving strokes make leaves without describing a single botanic detail. The shutters and jambs take broad, loaded swipes that leave ridges of impasto, catching real light like sun on painted wood. The sky is scrubbed thin, so the primed ground flickers through as ambient brightness. This orchestration—thick against thin, dragged against pressed—creates the feeling that the scene was not merely observed but felt: the sticky heat of paint itself becomes a stand-in for summer.

The Productive Role of Black

Black in this painting is not the absence of color; it is a structural partner that lets color sing. A strong black spine outlines the right jamb; thinner black notes articulate the interior edges of the shutters and parts of the sill. These accents behave like the lead of stained glass, bracing the brilliant panes around them. Without a handful of darks, the high key would drift. With them, the whole structure tightens, and the turquoise, pinks, and greens blaze brighter for the contrast.

The Window as a Picture-Within-the-Picture

Matisse had long been fascinated by the motif of a window, and here it becomes a manifesto. The outer painting contains an inner one: within the dark bars and hot shutters lies a second rectangle—a pure landscape of sea, sky, and boats. That internal picture is itself framed by vines and terracotta pots, as if nature and culture conspired to crown it. The device is more than clever design. It stages painting’s central paradox: we look at a flat surface that proposes depth. The window makes that truth explicit by turning the act of viewing into the subject.

Space Without Linear Perspective

A classic interior-to-exterior view would use converging lines to set depth. Matisse achieves recession through other means: overlapping planes, relative scale, and temperature. The pots sit before the sill; the sill before the sash; the sash before the harbor. Warm shutters step forward while the cool seascape slips backward. Boats shrink gently with distance, their masts rising like calligraphic strokes against sky. The result is convincing and modern: depth without diagram, space built as much from sensation as from geometry.

Light, Hour, and the Meteorology of Color

Everything in “Open Window, Collioure” suggests a bright day when the sun lies high but somewhat veiled—perhaps morning or late afternoon with heat in the air. Long shadows are absent; color is clear and strong; the sea adopts pinks and violets that ring true to Mediterranean light, which often tints water with reflected sky and sun-washed masonry. Highlights are not afterthoughts painted in white; they are built into the palette from the outset—pale lilac in the sky, cream in the water’s ripples, light pouring between impasto strokes on the jambs. The painting does not depict the sun; it shows what the sun does to surfaces.

Plants on the Sill: Threshold Between Worlds

The row of pots is more than decoration. They mark the border where domestic life meets the public harbor. Their earthy oranges, reds, and cobalt blues tether the interior to the exterior as a string of visual knots. The leaves, painted in rapid green and yellow notes, echo the movement of water below, creating a bridge of rhythms across the threshold. The plants stand for transformation: earth in fired clay nourishes greenery that leans toward sea and sky—a small cycle of containment and release that mirrors the window’s larger drama.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Gaze

The composition orchestrates a clear path for the eye. Begin at the heavy black bar on the right; feel how it locks your position, like a doorjamb grasped by the hand. Slide inward along the orange-pink shutter and bounce across the sill’s pots, each a little drumbeat of color. Lift into the square of the view, where the pink water ripples under short, blue dashes and the masts tilt like musical staffs. Climb to the cool transom dotted with vine, then return down the left jamb’s garland to the warm interior again. Looking becomes a loop—outward to the bay, inward to the room, outward again—equal parts breath and heartbeat.

Decorative Intelligence and Living Nature

The picture displays Matisse’s love of decorative art—fabrics, tiles, paper cut patterns—without sacrificing the feel of a real place. Ivy and geraniums read as motifs, yet they retain botanical bounce. The water’s marks are ornamental, yet they behave like waves. Interior woodwork holds flat bars of color that recall printed cloth; still, they register as sun-hot surfaces you could touch. The power lies in the balance: decor does not mask nature; it reveals its underlying rhythms.

Dialogues With Earlier and Later Windows

“Open Window, Collioure” anticipates a long line of interiors and windows in Matisse’s career. Compared with the denser “Collioure Interior,” the structure here is cleaner and the threshold clearer. Later Nice-period windows soften into long, languorous chords, while this early Fauve window crackles with voltage. Decades on, the logic of framing and color architecture culminates in “The Red Studio,” where walls themselves become a single field of hue. The seed is visible here: color can be both surface and space, frame and view.

Material Truths and the Sense of Place

Texture carries meaning. Thick ridges on the shutter edges catch real light, reenacting the heat of a Mediterranean afternoon. Scumbled areas where the white ground glows through conjure glare better than any polished highlight. The rough weave visible in places reads like plaster warmed by sun. These material facts make the picture more than a visual report; they make it a physical souvenir of standing at that window in summer.

The Emotional Register of Complementary Color

Matisse believed that art should offer balance and a tonic calm, even at high volume. The painting delivers exactly that. Hot oranges and magentas hum against cool aquas and violets, yet the scene never feels hectic. Black provides ballast, and repeating greens in vine and pot plants bind the palette. The feeling is one of charged ease: open air floods the room, but the window’s strong architecture holds it in a hospitable embrace. You sense both the invitation to step out and the comfort of staying in.

Why the Painting Still Feels New

More than a century later, “Open Window, Collioure” remains fresh because it relocates accuracy from detail to effect. It does not tally every shutter slat or plank in the boats; instead, it records how bright coastal light simplifies things into zones. By leaving reserves of primed canvas and trusting vibrant complementary chords, Matisse offers a version of truth that photography rarely delivers: how it feels to squint into a harbor from a cool room, where color seems to be the very substance of air.

How to Look So the Picture Opens

Stand close and study the edges where hues meet. See how a narrow seam of black between orange and green stiffens a shutter’s edge more decisively than laborious modeling could. Step back and let the bright central panel take over: the pink water alive with blue strokes, the masts like quick exclamations, the pale horizon breathing between sea and sky. Drop your gaze to the pots and feel the weight of clay stated by a handful of thick touches. Finally, allow your eyes to follow the loop of the frame again. The painting rewards repeated circuits, each round tightening your sense of its internal music.

A Threshold Between Painting and the World

The open window is a hinge that dramatizes the nature of art. Inside, color becomes architecture; outside, architecture dissolves into color. The sill marks the meeting of those realms, where Matisse sets earthy vessels bursting with leaf. The scene is at once a specific morning in a fishing town and a general proposition about looking: to open a window is to accept that the world enters as rhythm and temperature before it becomes objects. With brush and pigment Matisse translates that entrance into a language the eye can inhabit.

Conclusion: A Harbor Built of Color and Air

“Open Window, Collioure” is more than a lovely view. It is a compact manifesto that shows how color can be structure, how reserve can be light, and how a simple domestic motif can hold a world. The shutters’ hot planes, the cool depths of the sea, the garland of vine, and the chorus of pots together generate a complete experience of space and mood. The painting remembers the physical pleasure of looking from shade into brilliance and gives that moment a durable form. In doing so, it not only defines a season in Matisse’s life but also announces a modern way of seeing that still feels inexhaustibly alive.