Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

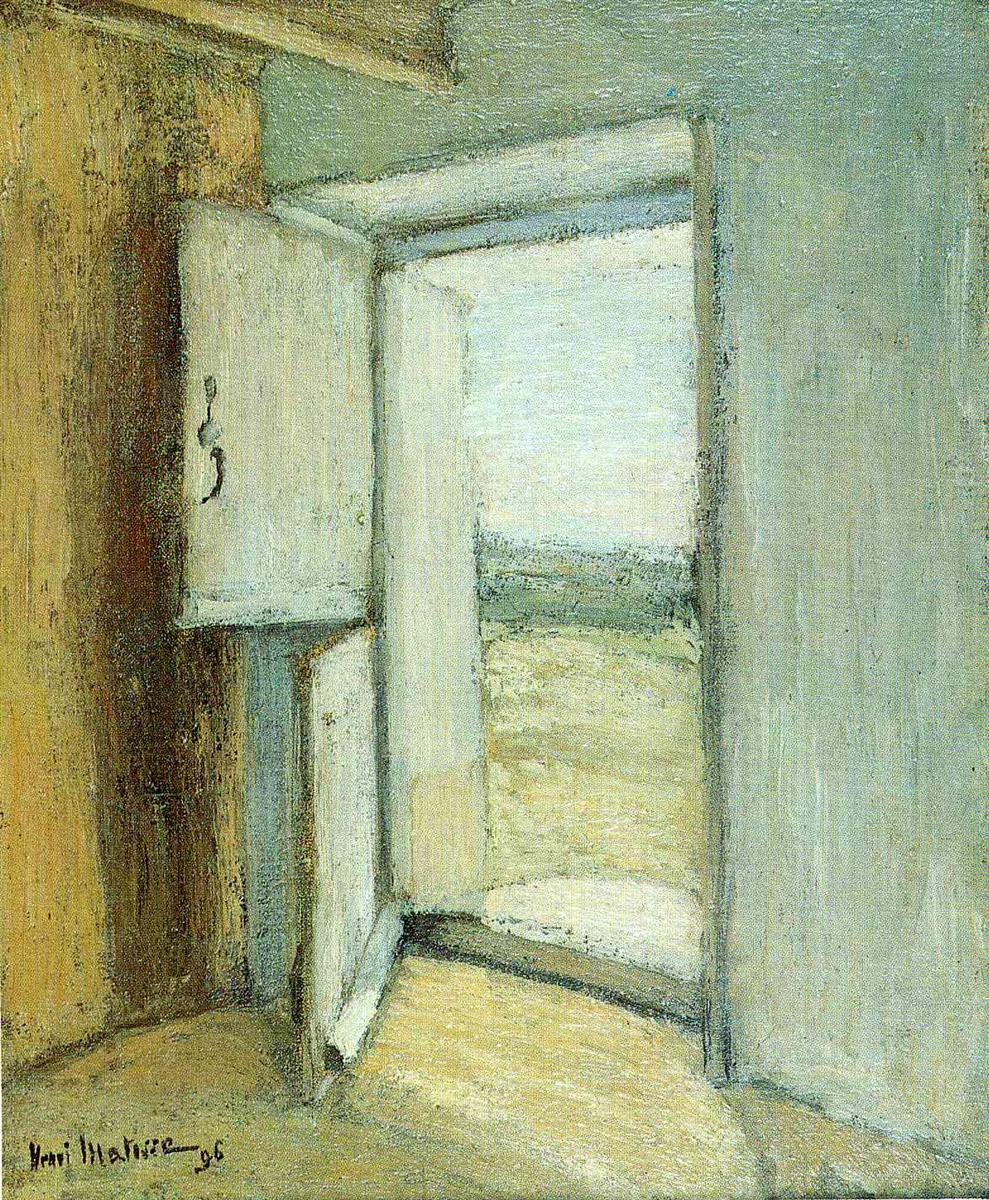

“Open Door, Brittany” is a small but resonant painting from 1896 in which Henri Matisse turns an ordinary threshold into a study of light, space, and the poise between interior and exterior. The composition is startlingly simple: a door stands ajar, its panels tilted toward us; beyond it a slice of landscape flattens into pale bands; across the foreground the floor gathers light in a shallow arc. There are no figures, no furniture, and almost no color in the conventional sense. The picture lives by value, temperature, and surface. Instead of describing things, Matisse measures relations—verticals against horizontals, cool grays against warm ochres, matte walls against the soft gleam of daylight—until the room breathes. The result is a quietly radical statement about how painting can turn the most modest motif into an arena for perception.

Historical Context and the Brittany Crucible

The year 1896 marks a turning point in Matisse’s development. Having absorbed academic training, he went to Brittany and to the Atlantic island of Belle-Île seeking a more direct experience of light and weather. There he painted seascapes, villages, and interiors that demanded structural clarity and economy. “Open Door, Brittany” belongs to this period of disciplined reduction. While his cliff studies wrestle with mass and thrust, the door interior concentrates on the logic of planes and the orchestration of whites. The painting demonstrates how, even before his Fauvist leap, Matisse was learning to rely on relationships rather than on description, transforming a room into a set of forces that hold each other in balance.

The Motif: A Threshold and Nothing More

The motif could not be humbler. We stand in a tight corner of a room, looking toward a door that opens onto a bright outdoors. The left jamb carries a small cupboard door or inner shutter; the right jamb is blunt and broad. The opening itself is curved slightly by the way light pools on the floor, as if the threshold were rounded or the boards warped. Through the door we do not see narrative detail, only delicate stripes of distant field, shoreline, and sky. Matisse strips the scene to essentials—wood, plaster, light, air—so that the experience of standing at the doorway becomes the subject.

Composition and the Architecture of Planes

The composition is built from a few large rectangles and one governing curve. A vertical band of warm, scrubbed wall occupies the far left; the open door forms a pale central frame; the right wall is a cooler, nearly uniform expanse that steadies the image; the floor arcs from left to right in a gentle sweep that registers the fall of light. These pieces interlock like carpentry. The central opening is slightly off-center, which prevents symmetry from turning static. The narrow bevels of the door panels introduce tiny perspectives that lead the eye outward, while the curved shadow on the floor tethers our gaze to the room. Everything is designed to make the viewer feel both the urge to step outside and the quiet pull to remain.

Color Architecture and the Poetry of Whites

Although the palette is restrained, the color is never monotonous. Matisse constructs “white” as a chord rather than a single note. The door’s planes lean toward cool pearl and thin blue-gray; the right wall carries a faint greenish cast; the left wall retains warmer ochres and rubbed siennas; the floor is woven from straw-yellow, putty, and ash. By setting these temperatures against one another, he makes light feel active without deploying saturated hues. The exterior bands beyond the threshold introduce the softest tints—subdued blue for sky, a muted olive for land—which stabilize the interior whites and keep them from floating. In this sense the landscape is not a view but a color counterweight.

Light, Weather, and the Northern Key

The light is distinctly northern and maritime, the kind that cools shadows and turns highlights milky rather than blazing. There is no theatrical sunbeam; illumination arrives as a steady pressure that fills the space and settles onto the floor in a gradual fan. Matisse’s handling of this light is precise. The threshold’s inner edge is a crisp value flip; the jambs receive softer halftones; the exterior is bleached to a pale haze that compresses distance, as if a cloudy sky makes the landscape shallow. Through this discipline the room acquires time. We feel an hour in the day when the world brightens evenly and the invitation to step outside is gentle rather than urgent.

Brushwork and the Material Fact of Paint

The painting’s surface is a map of decisions. On the walls, Matisse uses dry, dragged strokes that allow the ground to breathe, creating the chalky texture of plaster. Along the door edges the brush becomes narrower and more deliberate, laying small, parallel striations that read as planed wood. In the opening to the outdoors, strokes are horizontal and lightly blended, evoking air and distance without fussy detail. The floor carries the heaviest touch: thicker, warmer paint is pulled in arcs, so that the surface seems to tilt toward us. This variety of handling is not decorative. It is how the picture persuades, translating texture into a language of touch we can read at a glance.

Space, Depth, and the Edge of Abstraction

Matisse constructs depth with almost nothing. There are no measured vanishing points, no skirting boards or cast shadows to diagram perspective. Instead he stacks space through adjacent planes and value steps. The near walls are gently darker than the door frame; the exterior is lighter than all; the floor turns in space because temperature and value change together as it curves. Abstraction hovers at the edges. Remove the door handle and the signature and the image could resolve into a set of pale blocks crossed by a soft arc. The fact that it remains legible as a room is a tribute to how finely tuned those relations are.

White as Subject and the Foreshadowing of Fauvism

The real subject of “Open Door, Brittany” is white—how it shifts, breathes, and absorbs ambient color. This concern anticipates Matisse’s later interiors, where sunlit walls and gauzy curtains become fields of modulated white that carry the entire harmony. Even in 1896 he is already refusing to treat white as neutral. Instead, it is alive with neighboring tints and therefore capable of creating space and emotion on its own. This decision plants the seed for his Fauvist leap. When color later explodes, it will do so upon a grammar learned here: assign each plane a precise temperature, let edges arise from color meets, and trust that a few large fields can hold the scene.

Silence, Threshold, and the Psychology of Place

The painting’s mood is distinctly quiet. An open door usually implies passage and narrative, yet here the world beyond is emptied of incident. The image becomes a meditation on potential rather than action. The curved floor reads like a pause; the exterior bands suggest breadth and freedom but remain remote; the cool whites of the jambs keep us indoors. Many viewers sense an emotional undertone—calm, hesitancy, or expectancy—arriving not through storytelling but through spatial poise. The threshold motif carries its own symbolism of transition, and Matisse tunes every relation to keep us poised on that hinge.

Cropping, Scale, and the Viewer’s Body

The cropping is intimate. We are close to the jambs, almost pressed into the corner, the way one stands when listening or preparing to step through. This bodily proximity matters. It converts the door into an event rather than a distant object. Scale reinforces the effect. The door feels slightly larger than life because the picture excludes the ceiling and the far wall; our eyes climb the panels and meet the light at their height, as they would in real space. Matisse’s decision to compose the scene from this vantage makes the painting participatory. We stand where he stood, feeling what he felt about distance, light, and choice.

Parallels and Dialogues with Other Painters

Although “Open Door, Brittany” is entirely Matisse’s, it converses with a broader lineage. The tonal hush and sense of suspended time recall northern interiors that privilege light over incident. The economy of means and reliance on value steps nod to Chardin’s discipline. At the same time, the insistent structure and the refusal of anecdotal finish echo his growing admiration for painters who built space from planes and color relations rather than from detailed drawing. What distinguishes Matisse is the frankness of his means. Instead of polish he offers clarity; instead of symbol he offers structure. The door becomes a modern problem solved with a few clean moves.

Technique, Ground, and Layering

A warm ground seems to underlie the entire painting, surfacing in rubbed passages along the left wall and under the floor’s halftones. Matisse often scumbles thin layers so that this undertone pulses through, unifying the whites and preventing them from going chalky. Edges are rarely drawn; they result from one plane abutting another at just the right value and temperature. Where the exterior meets the inner frame he keeps the seam soft, letting air intrude. Where the floor meets the jamb he sharpens the line, anchoring the interior. This orchestration of thin and thick, soft and hard, is as important to the painting’s success as its composition.

Rhythm and Movement Across the Surface

Even in its quiet, the picture has rhythm. The left wall’s vertical strokes steady the eye; the door’s bevels nudge it outward; the exterior bands carry it horizontally; the floor’s curve returns it, like a slow breath. Repetition of tones—cool whites in frame and right wall, warmer whites in left wall and floor—creates beats that move attention without words. This rhythm is the painting’s secret engine. It ensures that a nearly empty room does not go inert but keeps the viewer gently circulating.

Relationship to Matisse’s Interiors and Later Work

Seen alongside Matisse’s interiors from the Nice period, this early painting reads like a blueprint. Later rooms teem with patterned screens, flowers, and figures, yet the structure beneath is similar: large planes of modulated white, a window or door that opens onto softened bands of landscape, and a floor that captures the spill of light. He will brighten the key and thicken the palette, but he will continue to trust the architecture of planes refined here. “Open Door, Brittany” is therefore not a detour but a foundation stone, proving that emptiness can be eloquent when relations are exact.

How to Look at the Painting Today

Begin by letting your eyes adjust to the tonal key. Stand close and watch how many temperatures live in the so-called whites: olive on the right wall, pearl on the door, honey on the floor. Step back until the central opening reads as a single breath of light. Track the edge where exterior meets jamb and notice how softness there makes air palpable. Follow the floor’s curved shadow and feel how it keeps you inside even as the view invites you out. Finally, consider how little is described and how much is felt. The painting rewards slow looking because it was built from slow seeing.

Conclusion

“Open Door, Brittany” turns a plain doorway into a disciplined meditation on light, place, and the poised moment before passage. With a handful of planes, a narrow range of temperatures, and brushwork that alternates between rubbed plaster and luminous halftone, Matisse composes a room that feels inevitable. The painting shows him moving beyond academic finish toward a language where edges are agreements between colors and where whites carry emotion. If his later fame rests on audacious hues, the authority of those colors is rooted in works like this one, where economy becomes clarity. The door is open, the world is near, and the painting teaches us to recognize the subtle power of relations that hold steady in a quiet room.