Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

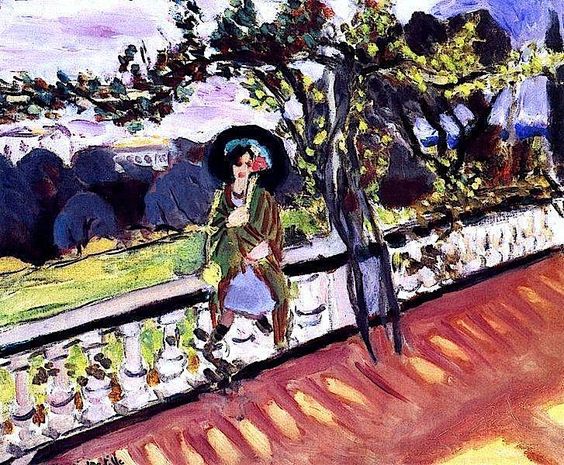

Henri Matisse’s “On the Terrace, Parc Liserb” captures a moment of poised leisure on a sun-warmed balustrade overlooking a lush public garden. A fashionable woman in a broad hat sits near a sinuous tree whose trunk splits and arcs over the terrace. Below, dark, rounded foliage masses push up like ocean swells; above, a lilac sky breaks in pale bands; and across the foreground the terrace pavement glows with ruddy stripes of light. With just a few tuned colors—brick reds, spring greens, deep blues, and violet greys—Matisse composes a scene where architecture, nature, and modern dress share the same visual tempo. The painting belongs to his Nice-period vocabulary, in which color acts as climate, pattern becomes structure, and contour conducts attention without choking it.

A Nice-Period Conversation Between City and Garden

The Nice years gave Matisse rooms and terraces that faced the Mediterranean or opened onto manicured parks. Here he exchanges the privacy of an interior for an elevated, public edge where a person can watch the garden as if it were a stage. Parc Liserb—spelled variously in records—functions less as a specific address than as a type: a cultivated landscape of paths, balustrades, and clipped trees where modern urbanites stroll. Matisse’s interest is not topographic reporting; it is the poise created when human presence and designed nature align. The terrace is both vantage and instrument, a platform from which color and line can orchestrate the eye’s movement through space.

Composition: A Diagonal Balcony and a Pair of Vertical Trees

The picture is organized by a few strong, simple bearings. A shallow diagonal sweeps from the lower left corner across the reddish terrace toward the middle distance at right; the white balustrade rides that diagonal like a steady, repeating rhythm. Countering it are two vertical masses: the split tree near center-right, with one trunk leaning and the other erect, and the seated woman whose posture compresses into a compact column under the breadth of her hat. The eye rides the terrace’s warm stripes, pauses at the figure, passes under the arching branch, then drops into the garden’s rounded foliage before climbing to the pale sky. The design gives a sense of promenading—step, look, pause, and continue.

The Balustrade as Visual Metronome

Matisse paints the balustrade’s repeating balusters with brisk, rounded strokes. They are not architectural pedantry; they are a metronome. Each white capsule catches light and sets the measure for the diagonal’s pace. Between them, small, greenish notes suggest trailing plants or moss, a softening that ties the baked terrace to the cool garden below. The long, dark rail atop the balusters is a crucial structural line: it divides human footing from the sea of foliage, and it supports the figure like a musical staff supports a melody.

Color Climate: Brick, Leaf, Indigo, and Lilac

The palette is economical and decisive. Across the foreground, brick-reds and siennas carry the heat of sunlit paving; these warm stripes lean toward orange where the paint is thinned and toward maroon where shadows gather. The garden is a chorus of dark, blue-greens and inky indigos, brushed in overlapping, rounded swells that feel vegetal without counting leaves. The sky drifts between lilac and pearl, with faint warm seams near the horizon. The woman’s clothes connect the registers: a soft blue skirt picks up the sky’s coolness; a greenish shawl and hatband link her to the trees; and small bits of black—hat brim, shoes, drawing accents—stabilize her silhouette. Everything breathes in the same weather.

The Figure: A Compact Column Under a Broad Hat

Matisse compresses the sitter into a poised, vertical bundle. She faces slightly left, legs dangling from the balustrade, hands folded with a casual assurance. The broad, dark hat is not merely fashion; it is a compositional device that anchors the head as a clear, simple shape against the complex garden below. A pink flourish—perhaps a flower—warms the hat’s edge and touches her cheek with a local flare that keeps the face alive without detail. Her shawl reads as a soft green triangle that echoes the leaning tree’s diagonal, and her skirt forms a cool oval that sits securely on the rail. The contour is crisp where structure needs clarity—around the hat rim, along the forearm, at the shoe—then loosens into brushy edges where light and air ought to pass.

Trees as Architecture

The split tree does more than decorate; it builds the scene’s architecture. One trunk rises straight, the other pitches and twists, tying the terrace to the depth of the park with a living beam. Matisse lets the trunk’s blacks and dark olives thicken and thin like calligraphy, granting it the dignity of a structural column while keeping its organic character. The canopy, sprayed with light yellow-greens, pricks the sky in small moments that act like counterpoints to the balcony’s heavy rhythm. The tree unites organic and built order—precisely the harmony a designed park aspires to manifest.

Brushwork: Candor Over Finish

Across the painting, the brush remains candid. The terrace stripes are pulled in long sweeps that vary pressure; they carry the memory of a hand moving quickly, not an architect drawing a plan. In the garden, Matisse dabs and drags rounded forms into each other, letting undercolor breathe. Balusters are indicated rather than carved, their ovals left open in places so light leaks through. The figure’s face is a bundle of quick, decisive marks—eye, nose, lip—but the whole reads because value and placement are right. This candor resists fussiness and keeps the scene alive.

Light Distributed Like Air

There is no theatrical spotlight here. Illumination is a shared network: the terrace’s warm stripes brighten where they stand open to sky; the balusters pick up small highlights; the garden absorbs light into dark masses; and the sky floats a cool wash over the upper field. The woman’s clothes receive and mediate these changes—the blue skirt reflecting sky, the shawl recording nearby leaf tones. Because light is distributed through relations rather than imposed from a single source, the scene feels inhabitable instead of staged.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

The painting encourages a looping path for the eye. Many viewers enter from the lower left along the sunlit red bands, ride the balustrade’s metronomic ovals toward the figure, pause at the black arc of the hat, and then move up through the split tree into the pearly sky. From there, the eye descends along the darker canopy into the shadowed garden masses, crosses back under the rail, and returns along the terrace to begin again. Each lap reveals new incidents: a cool glint on a baluster, a green flicker in the hatband, a violet seam in the sky, a wedge of blue shadow under the figure’s dangling shoes. The composition is built for revisiting.

Pattern as Timekeeper, Not Ornament

Matisse’s pattern logic is audible everywhere. The balustrade’s repeats, the terrace’s stripes, the rounded foliage swells, and the dappled canopy strokes all operate like overlapping tempos: largo in the garden masses, andante for the tree boughs, allegretto along the terrace. Pattern is never an end in itself; it keeps time so color can sing.

Elegance Without Excess

The sitter’s outfit announces elegance—broad hat, touches of pink and green, a blue skirt—but Matisse refuses costume drama. No lace is counted, no heel is polished. Elegance arises from what the outfit does in the composition: the hat provides a decisive disc; the shawl links body to landscape; the skirt cools the surrounding warmth. This approach is classic Matisse: refinement measured by relational clarity rather than by detail.

The Terrace as Modern Social Stage

Terraces like this were built for looking and being seen, for the modern ritual of strolling and pausing. Matisse treats the space accordingly. The seated woman is composed but not posed; she inhabits a public edge with private calm. The painting does not turn the park into a spectacle or the sitter into a celebrity. Instead it celebrates a democratic luxury of early twentieth-century life: leisure arranged by civic design, shared vistas that belong to anyone who climbs the steps.

Depth Without a Vanishing Trap

The picture offers depth without trapping the viewer in a mathematical funnel. The terrace recedes gently; the balustrade’s ovals diminish, but not theatrically; the garden stacks in bands of foliage; and the sky lays back as a cool lid. Overlap and value do the heavy lifting. This method keeps the surface active and grants the painting a modern frankness: you see space, and you see the means by which it is made.

Sensation Over Description

Matisse’s genius is to persuade with sensation rather than inventory. You feel the baked terrace underfoot though no bricks are rendered; you sense leafy density though no leaf is counted; you catch the coolness of the sky with a few horizontal washes. The mind composes the rest because the relationships are accurate. The impression is durable because it engages the viewer’s own experience—heat, shade, breadth, and pause—rather than drenching the eye in detail.

A Dialogue With the Fauvist Past

Though calmer than his Fauvist explosions of the previous decade, the painting preserves that era’s conviction that color can carry structure. The red terrace and dark garden collide like complementary chords, yet neither overpowers the other because the balustrade, tree trunks, and hat provide strong, drawing-based anchors. It is a synthesis: the stability of line married to the freedom of color.

The Ethical Dimension of Ease

Matisse once wrote that he wanted his art to be “like a good armchair.” On this terrace, that idea becomes civic: a good balustrade, a good path, a good view. Ease is not indulgence; it is a condition that allows attention to ripen. The figure looks, the viewer looks, the park receives both quietly. The painting makes a claim for the dignity of public leisure and for the civilizing power of designed nature.

Why the Image Endures

The scene stays in memory because its order feels inevitable once seen. The brick-red sweep, the white metronome of the balustrade, the seated figure stabilized by a black hat, the split tree tying terrace to sky, the cool garden breathing underneath—all interlock with clarity. You can re-walk the terrace in your mind and reinhabit its tempo. The painting’s frankness of touch and economy of means keep it perennially fresh.

Conclusion

“On the Terrace, Parc Liserb” is a chamber piece for architecture, foliage, dress, and light. The terrace provides the beat; the balustrade counts it; the garden hums a deep, cool drone; the sky floats a lilac ceiling; and the seated woman delivers the human melody with a few assured notes. Matisse’s Nice-period poise is fully present: color tuned into climate, line used like a conductor’s baton, and pattern assigned the task of keeping time. The result is a modern classicism that dignifies a modest act—sitting on a terrace and looking—by arranging every visual element so that attention itself becomes the subject.