Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

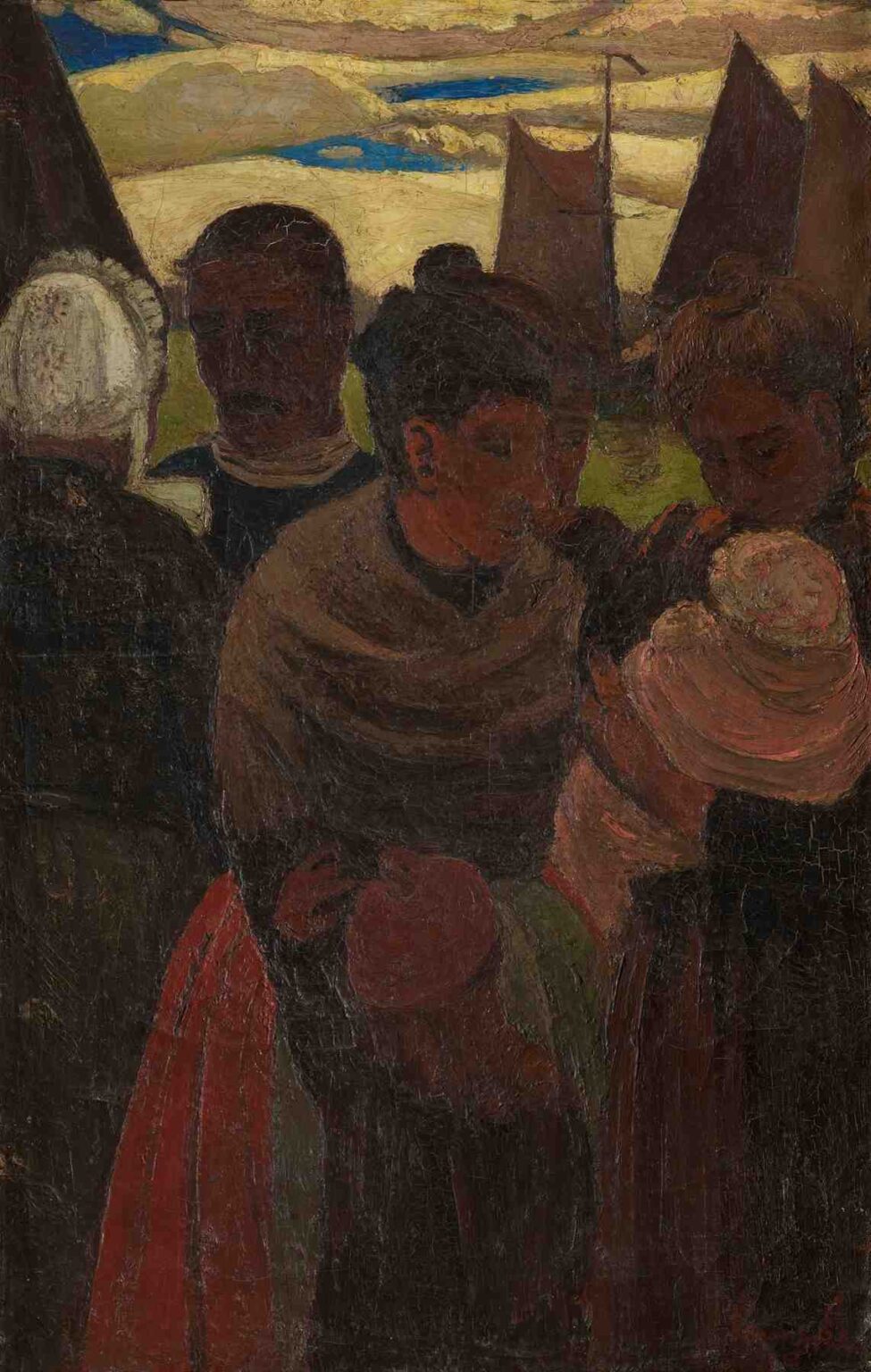

Constant Permeke’s On the Quay (1913) captures a moment of introspective stillness amid the bustle of a fishing port. Painted shortly before the outbreak of World War I, the work exemplifies Permeke’s early Expressionist leanings and foreshadows his mature focus on human dignity under duress. In this oil on canvas, he portrays Breton fishermen and women standing on a quay, their forms rendered with earthy palette, sculptural solidity, and an emotional gravity that transforms an ordinary harbor scene into a profound commentary on labor, community, and the elemental forces shaping their lives. By examining its historical context, compositional strategies, color harmonies, brushwork, and symbolic resonance, this analysis reveals how On the Quay embodies Permeke’s unique synthesis of rural realism and Expressionist depth.

Historical and Cultural Context

Painted in 1913, On the Quay emerges at a pivotal moment in European art and society. The Belle Époque was giving way to geopolitical tensions, yet on the Brittany coast, centuries-old fishing traditions persisted. Permeke traveled to coastal villages to document the working lives of fishermen and their families, drawn to their resilience against wind, tide, and economic uncertainty. The quay—where boats dock, nets are mended, and catches sorted—served as both workplace and social hub. In depicting this setting, Permeke pays homage to the communal rhythms of Breton life while signaling broader themes of human perseverance in the face of modern upheavals.

The Artist’s Early Expressionist Style

By 1913, Permeke had begun to deviate from the academic naturalism taught at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. Influenced by Vincent van Gogh’s emotional use of color and the bold forms of Paul Cézanne, he pursued an Expressionist idiom that emphasized subjective experience over photographic detail. On the Quay displays these tendencies: figures are simplified into monumental shapes, outlines are emphasized, and color is deployed less to record reality than to convey mood. This early Expressionist phase laid the groundwork for Permeke’s later, more austere works produced after World War I.

Subject Matter: Fishermen and Community

At the heart of On the Quay are the figures themselves—men and women who depend on the sea for survival. Permeke avoids anecdotal storytelling; instead, he arranges the fishermen in a frontal, almost confrontational manner, their faces solemn, their postures steady. A woman in traditional Breton dress appears at left, her coiffe (lace headdress) painted with delicate attention, signifying regional identity. To her right, two male figures stand shoulder to shoulder, their torsos broad and heavy as if molded from clay. By focusing on these individuals in a communal setting, Permeke honors the interconnectedness of coastal life: each body of labor supports the others in a shared enterprise.

Compositional Structure

Permeke divides the canvas into horizontal bands that echo the layering of sea, land, and sky. The lower third is occupied by the quay’s stone surface, rendered in muted grays and ochres. The central band presents the standing figures, their silhouettes overlapping to create a unified mass. Above them, masts and wrought-iron cranes puncture the middle ground, connecting the human realm to the rigging of fishing vessels. Finally, the upper third contains a turbulent sky—clouds swirling in ochre and cobalt—evoking the ever-present threat of storms. This tripartite structure grounds the scene in a tangible environment while reinforcing the figures’ relationship to their elemental surroundings.

Spatial Ambiguity and Monumentality

Rather than employing strict linear perspective, Permeke flattens space to emphasize the figures’ monumentality. The quay’s surface angles slightly toward the viewer, but the background boats and distant shoreline remain roughly on the same plane. By minimizing depth, he transforms the fishermen into imposing presences who dominate the pictorial field. This flattening also aligns with modernist experiments of the time, including Post-Impressionism and early Cubism, which sought to break free from the illusion of three-dimensional space and instead highlight the painting’s surface and form.

Color Palette and Emotional Resonance

On the Quay uses a restrained, earthy palette dominated by ochres, umbers, deep greens, and slate grays, offset by touches of milky white and rust red. The fishermen’s smocks and skirts, painted in muted sepia and olive, harmonize with the quay stones, visually linking the people to their environment. The sky’s ochre hue suggests a setting sun or an impending storm, adding emotional tension. Crucially, small accents—a woman’s white coiffe, the pale rope loops, and flecks of sea-blue on boat hulls—create focal points that guide the viewer’s eye across the canvas. This tonal economy reinforces a somber mood: the workday ending but rest and respite still distant.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Permeke’s brushwork in On the Quay alternates between broad, sweeping strokes and more detailed dabs. The sky is rendered with loose, swirling brushstrokes that convey movement and instability. In contrast, the figures’ clothing and features receive more controlled, directional strokes that model volume. The stone surface of the quay is built with layered scumbles, imparting a gritty texture suggestive of salt and sand. This varied handling of paint enriches the canvas’s tactile quality and underscores the contrast between the world’s solidity underfoot and the sky’s capriciousness overhead.

Light, Atmosphere, and Time of Day

Permeke captures a fleeting moment at dusk, when residual daylight merges with gathering clouds. The lighting is diffuse, with no single source, yet highlights catch the upper edges of garments and faces, suggesting illumination from a low sun. The women’s coiffe glows with a faint luminescence, drawing attention to her presence. Meanwhile, the men’s broad shoulders create shadows that reinforce their physical weight. This interplay of light and shadow conveys both the end-of-day lull and a latent tension: the sea’s dangers lie just beyond the quay. The atmospheric subtlety invites viewers to contemplate the passage of time and the uncertainty of the next tide.

Symbolism and Thematic Depth

Beyond its literal scene, On the Quay carries layered symbolism. The quay itself represents stability—man’s attempt to control the sea—while the looming boats and rigging in the background hint at labor’s perilous nature. The fishermen’s erect postures and steady gazes suggest resilience and dignity in the face of elemental forces. The woman’s traditional dress nods to cultural continuity, even as modern fishing equipment rises behind her. At a broader level, the painting meditates on human solidarity: multiple figures stand as a collective bulwark against external adversity. In this way, Permeke transforms a port tableau into an allegory of communal endurance.

Technique, Materials, and Conservation

On the Quay is executed in oil on canvas mounted on panel, a practice Permeke favored for its durability and the subtle textural effects it afforded. Recent conservation examinations reveal that the painting’s original varnish layer yellowed over time, muting some sky and coat highlights; careful cleaning restored the intended contrasts. Infrared reflectography shows preliminary charcoal underdrawings mapping the figures’ positions, while X-ray fluorescence confirms the use of natural earth pigments—ochres and umbers—consistent with Permeke’s rural palette.

Comparison with Permeke’s Coastal Works

On the Quay shares affinities with Permeke’s other coastal paintings from the 1910s, such as Fishermen Hauling In Nets (1912) and Women Mending Nets (1914). In each, the artist balances figural monumentality with environmental drama. However, On the Quay stands out for its focus on the transitional space between shore and sea, highlighting the human “gateway” rather than the fishing process itself. This emphasis on communal gathering rather than individual labor anticipates Permeke’s postwar interior sequence, where he explored group rituals in domestic settings.

Reception and Legacy

Although overshadowed by Permeke’s later, more austere masterpieces, On the Quay has garnered renewed interest in recent retrospectives. Critics appreciate its blend of early modernist experimentation and profound empathy. The painting offers a crucial link in understanding Permeke’s evolution: from youthful engagement with coastal realism to mature Expressionist exploration of inner experience. Today, On the Quay is hailed as a pivotal work that bridges genre painting and modernist abstraction, cementing its reputation as a touchstone of Flemish Expressionism.

Viewer Engagement and Interpretive Possibilities

On the Quay invites viewers to step into the fishermen’s world and reflect on themes of work, tradition, and communal ties. The painting’s spatial ambiguity and muted tonality encourage personal projection: one might imagine hearing gull cries, feeling the salt breeze, or sensing the creak of masts. Its universal symbolism—resilience amid uncertainty, solidarity in ritual—resonates across cultures and eras. Whether approached as a historical document or a timeless allegory, the work engages audiences with its emotional authenticity and formal inventiveness.

Conclusion

Constant Permeke’s On the Quay (1913) exemplifies the Belgian Expressionist’s early synthesis of rural realism and modernist form. Through its carefully balanced composition, earthy palette, dynamic brushwork, and symbolic depth, the painting transforms an everyday port scene into a powerful meditation on human endurance, cultural tradition, and communal unity. Over a century since its creation, On the Quay continues to captivate with its atmospheric subtlety and sculptural presence, affirming Permeke’s legacy as a master of art that speaks to both specific communities and universal human experiences.