Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

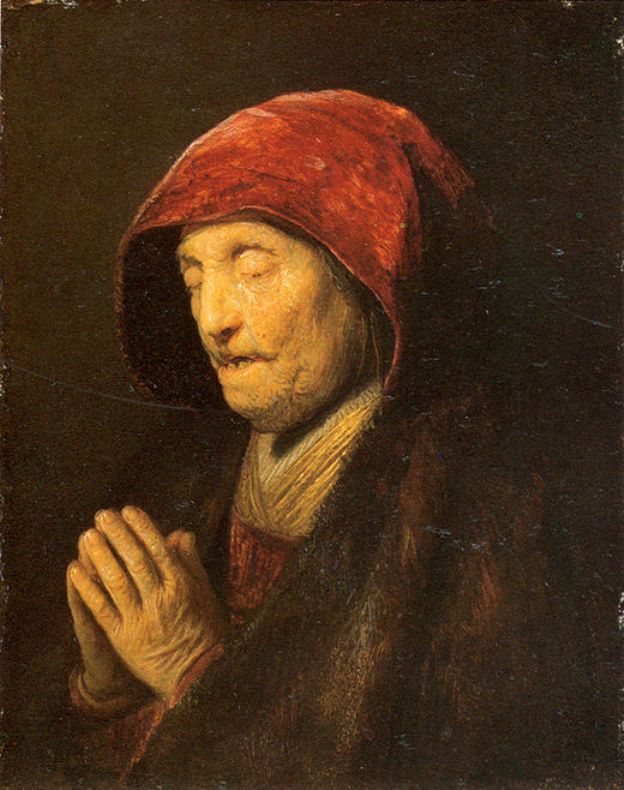

Rembrandt’s “Old Woman in Prayer” (1630) renders devotion as something tactile, interior, and near. A solitary figure turns three-quarters to the left, eyes lowered, hands interlaced and raised toward her chin. A red hood shelters the lined face; the fur or wool of a dark mantle absorbs nearly all the surrounding light. What remains of illumination gathers on skin and folded fingertips, slipping along the bridge of the nose and the furrowed brow before fading into the hush of the background. The painting is small, yet it has the gravity of a chapel. With chromatic restraint and exquisitely observed gesture, the young Rembrandt translates prayer from an abstract idea into a living, embodied act.

Historical Context and Subject

The year 1630 sits at the end of Rembrandt’s Leiden period, just before his move to Amsterdam. At this point he had already mastered the expressive possibilities of etching and was experimenting with how light could serve as the true protagonist of a painting. Dutch viewers of his day were steeped in scripture and accustomed to devotional images that avoided Catholic iconography while honoring inner piety. “Old Woman in Prayer” participates in this culture of quiet devotion. It may depict an anonymous elder, a tronie designed to explore expression, or even a model long thought to be his mother—yet the painting refuses to rely on identity. What matters is the human fact of prayer, shown without attribute or narrative, distilled to face and hands.

The Theology of Light

Rembrandt’s light is never merely optical; it is spiritual and ethical. Here it arrives without a visible source, as if emanating from the act of prayer itself. The hood and coat drink much of the illumination, allowing the remaining light to be invested primarily in the features and the clasped hands. The distribution is purposeful. Light rests where attention rests—on the skin worn by years, on fingers that have worked and now articulate supplication, on the thin line of lips murmuring words too private to hear. The background recedes to a warm darkness that feels less like emptiness than like silence. The effect is not theatrical contrast but reverent clarity: light that does not expose so much as accompany.

Composition and the Choreography of Devotion

The figure sits close to the picture plane, cropped at the elbows and shoulders to concentrate the viewer’s attention on the triangle formed by hood, face, and hands. That triangle is the engine of the composition: its apex at the fingertips directs the eye back to the face, while the long slope of the hood returns it to the folded wrists. The rhythm is circular, matching the cycle of inward attention in prayer. The slight angle of the head and the forward press of hands create a gentle vector that resists the static. One feels a pulse of breath between palms and chin. This choreography translates interior motion into visual fact.

Color, Texture, and Temperature

Rembrandt builds the picture with a limited palette—deep reds and russets, warm ambers, and earth blacks tempered by olive browns. The red hood functions as the single strong chromatic accent. Its tonality is not flamboyant but weathered, like cloth handled many seasons. The flesh is modeled in soft oranges and pale creams, with micro-shifts of pink along the knuckles and eyelids that evoke thin skin. The coat is a mass of dark, soft brushwork, alternately feathery and opaque, whose subtle variations swallow peripheral light and drive warmth back into the illuminated zones. The temperature scheme—warm light against warm dark—creates intimacy rather than glare. Nothing feels icy or remote; the entire image glows with human nearness.

The Psychology of Hands

Few painters equal Rembrandt in hands. In this canvas the interlaced fingers are not an emblem but a study in anatomy and feeling. The joints are knotted, the nails short, the tendons hinted, the skin thin and mottled. Yet the pose is relaxed rather than rigid. The thumbs cross lightly; the wrists touch with the ease of habit. Prayer here is not a dramatic seizure but a seasoned practice—the body remembering what the mind desires. The hands also serve as a second face. Their texture holds light with a delicacy that parallels the eyelids and cheeks, signaling vulnerability, labor, and gentleness all at once.

The Face: Age as Illumination

The old woman’s face is a landscape of time, but it is never cruel. Fine wrinkles are mapped with tender specificity; the downturned mouth suggests concentration rather than bitterness; the closed eyes gather stillness like cups. Rembrandt paints the forehead and cheek with shallow transitions of value rather than hard lines, letting breath shape the form. The chin is slightly tucked back, generating a small pocket of shadow that deepens the sense of inwardness. The overall effect is less portrait than presence: age is not a subject to be cataloged but a medium through which light must travel to reach us.

Materiality and the Ethics of Attention

The hood’s fabric, rendered with short, directional strokes and soft impasto, behaves like a shelter for the senses. Its inner rim darkens, then lifts into a bright edge that catches the highest light—a visual whisper that the act inside it matters. The coat’s dark pile is painted with longer, dissolving strokes, never over-described. Such restraint is ethical. It keeps the painting from turning into a demonstration of skill and instead directs skill toward honoring what is seen. Even the small scarf tucked at the neck—a braid of warm tones—quietly affirms the sitter’s dignity. No accessory becomes symbolic; each exists as something used and cherished.

Space, Silence, and the Invisible Room

The background is an enveloping brown that suggests neither chapel nor domestic interior. Its indeterminacy is deliberate. By refusing to specify place, Rembrandt allows prayer to occur wherever the viewer is. The darkness feels close yet breathable, like a room at evening when conversation dwindles and thought concentrates. The composition makes the viewer lean in, as one would near a friend who speaks softly. This spatial intimacy is central to the painting’s power; the image occurs at conversation distance, not at altar distance.

Technique and Surface

Close looking reveals a careful alternation of paint handling. The face is laid in layered, semi-opaque passages with tiny, enlivening touches of lighter pigment around the eyes and nose. The hands show thin, translucent glazes that allow ground tones to warm the skin from beneath, punctuated with firmer highlights along knuckles and nail ridges. The hood employs thicker, more tactile paint that records the brush’s direction, suggesting nap and wear. These shifts in handling provide tactile credibility: we feel the difference between flesh, cloth, and fur without needing verbal explanation. The surface thus becomes a sensory analogue for devotion—varied, alive, and unified by breath.

Devotional Culture and Dutch Taste

Seventeenth-century Dutch Protestantism favored images that encouraged private reflection over public ritual. Paintings of reading, listening, and praying proliferated, often within humble domestic settings. “Old Woman in Prayer” resonates with that taste while transcending it. The work’s simplicity meets expectations; its depth exceeds them. Rather than stage a reader with a visible Bible, Rembrandt chooses a moment when the book is closed and the mind is open. By focusing purely on the act, he avoids didacticism and accesses something universal: the human capacity to address what cannot be seen.

The Red Hood as Icon Without Emblem

Though Rembrandt avoids conventional iconography, the red hood functions almost like an icon’s nimbus. Its color concentrates attention; its shape encloses a space of sanctity; its edge frames the face the way a carved border frames a panel painting. But here the “aureole” is cloth, ordinary and warm. The transformation is quietly radical: holiness is not announced from above but fashioned from the materials of daily life—wool, skin, breath, and light.

Relation to Rembrandt’s Elder Studies

The painting belongs to a broader inquiry into age that runs through Rembrandt’s early works. His etchings of “An Old Man with a Bushy Beard” or “An Old Man with a Large Beard” explore how line can hold weight and wisdom; this canvas explores how color and light can honor the same. In all of them, the artist resists caricature. He seeks the specific inflections by which lived years shape a countenance. The old woman’s serenity links her to later paintings where age becomes a vessel for compassion—the late self-portraits, the quiet awe of “The Jewish Bride,” the parental tenderness in “The Return of the Prodigal Son.” Seeds of that mature vision already germinate here.

Time, Breath, and the Choice of Moment

Rembrandt chooses the second before speech or after it, the breath between phrases of prayer. This is neither the beginning nor the end but the steady middle where devotion lives. The eyelids are not clenched; they drift downward with surrender. The mouth is relaxed, as if the words now come less from lips than from the inner life. The hands, too, describe a habit that precedes and outlasts any one petition. In this poised interval the painter finds eternity: time’s flow slowed to a luminous rest.

Humanism Without Sentimentality

“Old Woman in Prayer” is deeply humane without lapsing into sentiment. Nothing flatters; nothing pleads. The woman’s age is honored; her piety is taken as given. The painting asks the viewer to meet her with the same attention the artist gives: look long enough for light to show what is really there. In this way the work functions as an ethics lesson disguised as a portrait. To pay attention is to respect; to illuminate is to love.

The Viewer’s Role

Rembrandt composes the image so that the viewer becomes a participant rather than a spectator. Our gaze completes the circle from hands to face and back again; our proximity supplies the room that the background withholds. The painting invites silent companionship—a form of witness that is neither intrusive nor distant. Standing before it, one senses that noise would be out of place. The work has already created a small sanctuary, and the viewer’s quiet is part of its architecture.

Comparisons with Contemporary Painters

Other artists of the Dutch Golden Age painted old women reading or praying, often with meticulous still-life detail. Rembrandt distinguishes himself by reducing props to essentials and by letting value and color do the narrative work. Where others might signal piety with an open Bible or a candle, he trusts the human fact of hands and face. His brushwork is broader, his light deeper, his empathy more pronounced. The painting is less about the virtue of a sitter and more about the nature of attention itself.

Lessons for Artists and Viewers

For artists, the canvas offers a set of practical principles. Assign light to meaning; let the brightest passages fall where the picture asks the eye to dwell. Use texture to separate materials rather than outline. Keep backgrounds spare when you want silence. Build flesh with incremental value steps and spare, decisive highlights. For viewers, the lesson is parallel: slow down. The painting rewards unhurried looking, revealing, with time, not only minute facture but also the rhythm of a living person’s quiet.

Enduring Appeal

That the painting continues to move viewers centuries later owes to its combination of exactness and modesty. It is exact in the rendering of skin, cloth, and light; modest in scale and gesture. The work refuses spectacle and thus remains always fresh. No matter one’s beliefs, the painting records a recognizable state: withdrawal from the world into a discipline of attention, hope, and remembrance. Because the image speaks in the universal grammar of hands and face, it can be heard across cultures.

Conclusion

“Old Woman in Prayer” compresses Rembrandt’s early genius into a small, glowing compass. Light takes on the work of mercy; color shelters rather than dazzles; texture tells the truth without flaunting it. The hood’s red is the warmth of human presence; the hands’ interlace is the architecture of habit; the face’s serenity is the form of trust. In recording an act as intimate as prayer, the painting becomes its own devotion—a sustained, loving attention to a human being in the presence of the unseen. The viewer, invited into that attention, leaves with the sense that looking itself can be a form of blessing.