Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

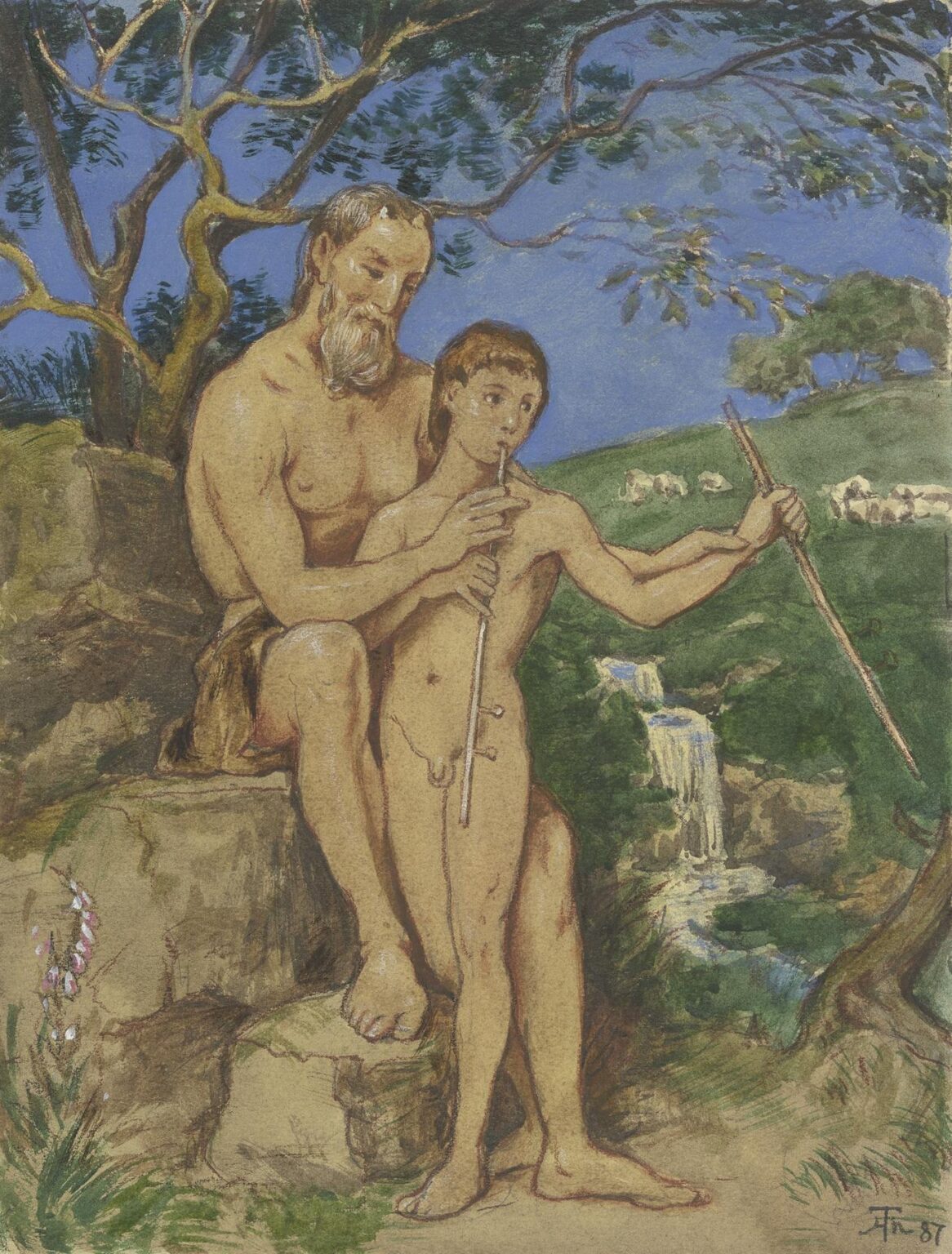

Hans Thoma’s Old and Young Faun (1887) captures a moment of gentle instruction and timeless ritual in an idyllic forest setting. Executed in watercolor and gouache on paper, the composition centers on two mythic figures—a mature faun and his youthful counterpart—poised before a cascading waterfall amid verdant hills. As the older faun guides the younger in the breath control and finger positioning needed to play a slender shepherd’s pipe, Thoma weaves together themes of nature, music, and the transmission of tradition. The painting’s harmonious balance of figure and landscape, its supple interplay of pigment and paper, and the nuanced emotional resonance of a teacher-pupil bond mark it as a singular masterpiece in Thoma’s oeuvre and in the broader late-19th-century revival of classical myth.

Mythic Resonance and Naturalism

Drawing on classical sources and rural German folklore, fauns represent hybrid creatures—half human, half goat—associated with forests, music, and untamed fertility. Unlike the overtly idealized satyrs of Renaissance art, Thoma’s fauns possess both human sensitivity and animal earthiness. Their elongated limbs, subtly cloven calves, and soft tufts of hair at the ankles evoke their bestial heritage, while their expressive faces convey empathy and concentration. Thoma’s intimate knowledge of woodland environments, acquired through lifelong exploration of the Black Forest, infuses the setting with botanical accuracy: trembling aspen leaves, bluebell stalks, and mossy boulders appear rendered with precise observation. The nymph of myth and the naturalist’s eye coalesce seamlessly, grounding the fauns’ otherworldly presence in a believable ecosystem.

Context of Creation and Artistic Climate

In the late 1880s, German art was undergoing a subtle shift. While academic history painting continued to dominate official salons, many artists sought solace and inspiration in nature and myth, a trend reflected in the Munich Secession’s early stirrings. Hans Thoma, already established through history tableaux and allegorical landscapes, embraced the opportunity to depict legendary beings in pastoral repose rather than dramatic action. Old and Young Faun thus bridges Romanticism’s fascination with mythic nostalgia and a burgeoning Realism that prized direct observation of the natural world. For urban patrons feeling the dislocation of industrialization, such works offered an imaginative return to simpler, bucolic origins—a sanctuary where human tradition and natural cycles remained in harmonious balance.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Thoma arranges the scene within a vertical rectangle that mirrors traditional devotional icons, suggesting reverence for the subject matter. The seated old faun and the standing young faun form a gentle S-curve that guides the viewer’s eye from top to bottom. At the apex, swaying branches frame the figures like a natural archway. The mature faun occupies the midground, seated on a stone outcrop that visually anchors the composition, while the youth stands on a lower ledge, his posture leaning into the elder’s instruction. Beyond them, a distant ridge of hills and a pure white waterfall punctuate the horizon, their verticality echoing the figures’ upright gestures. The foreground’s gently sloping ground, dotted with foxglove blooms and bracken, draws the eye back to the intertwined hands that illustrate the moment of teaching. This carefully calibrated interplay between figure and landscape yields both depth and intimacy.

The Coloristic Palette and Light

Thoma’s palette for this work is at once restrained and resonant. Earth tones—umber, sienna, and olive—dominate the fauns’ skin and the rocky ledge, linking them chromatically to their forest domain. The waterfall’s pale gouache highlights and the distant meadow’s sunlit green introduce lighter accents that animate the background. The sky, visible through interlaced foliage, is brushed in cool blue washes punctuated by soft cloud forms, establishing a clear midday or early-afternoon atmosphere. Thoma layers transparent watercolor glazes to build subtle gradations in shadow and form: the folds of the elder’s draped hide cloak, the youth’s ribcage contour, and the textured bark of birch trunks. Delicate strokes of white gouache on leaf edges and the fauns’ collars of hair capture fleeting sparkles of sunlight. This balanced deployment of warm and cool hues, light and shadow, fashions an immersive, luminous world.

Characterization of the Fauns

The elder faun exudes patient authority. His weathered visage—etched with lines of age and softened by a silvery beard—betrays both the wear of experience and the calm satisfaction of mentorship. His robust torso, partially draped in goat-hide, conveys primal strength restrained by civilized purpose. The youthful faun, in contrast, displays fresh nervous energy: his eyes widened in concentration, his lean frame turned slightly toward the elder in eager attention. Thoma conveys this dynamic through posture and gesture: the elder’s guiding hands delicately adjust the youth’s fingers on the pipe’s holes, while the younger’s free hand grips a knobby staff for balance. Neither figure appears static; the moment feels lived-in and evolving, imbued with the vitality of teaching and learning.

Symbolism of Music and Mentorship

Music, in ancient myth, often bridges the human and divine, transforming environment and spirit. The shepherd’s pipe, simple yet evocative, symbolizes communion between creature and cosmos: its pastoral tone conjures windswept hills, woodland glades, and the wild music of nature itself. By focusing on the act of instruction—rather than performance—Thoma shifts the emphasis to mentorship, the transmission of culture from one generation to the next. The youthful faun stands on the threshold of initiation, guided by the elder into the mysteries of sound and tradition. This ennobles the scene beyond mere entertainment, recasting it as a rite of passage mirrored in human experiences of apprenticeship and inheritance.

Landscape Details as Emotional Accent

Thoma’s forest glade is more than a backdrop: it amplifies the painting’s emotional tenor. The entwined trunks overhead form a cathedral-like canopy, sheltering the figures and underscoring themes of sacred teaching. The waterfall in the distance signifies continuity and renewal, its steady flow echoing the stream of knowledge passing from elder to youth. The grazing sheep near the ridge suggest pastoral peace and the reassurance of a self-sustaining world. Foxgloves at the foot of the rock—tall, bell-shaped flowers—symbolize both gentleness and the danger latent in beauty, reminding viewers that learning comes with responsibility. Through these botanical and topographical details, Thoma constructs a landscape that resonates with the characters’ inner journeys.

Technical Mastery and Medium

Watercolor and gouache demand confident, economical brushwork—qualities Thoma demonstrates in every leaf stroke and flesh wash. He likely began with a light graphite underdrawing to position major elements, then applied pale washes over the paper’s warm tone. Transparent watercolors build midtones, while opaque gouache accents yield highlights on the waterfall and figures. Thoma’s control of the medium is evident in the faun’s smoothly modeled limbs: successive glazes achieving sculptural volume without obscuring paper texture. Fine brush hairs articulate leaf veins and staff texture, while broad, energetic strokes capture the rock’s rugged surface. The subtle granulation of pigments in shadowed areas contributes to a tactile, organic feel, confirming Thoma’s reputation as both a meticulous draughtsman and a fluid colorist.

Emotional and Psychological Impact

Old and Young Faun invites viewers into a moment of shared trust and quiet wonder. The elder’s serene gaze and the youth’s tentative focus create an emotional counterpoint: wisdom guiding curiosity. The painting’s mood is neither sentimental nor didactic; rather, it embodies a respectful, reciprocal bond. Observers sense the gravity of a tradition in progress and the joy of discovery that accompanies first breath on a musical instrument. This emotional resonance transcends specific mythic references, speaking to universal experiences of teaching, learning, and the nurturing connection that sustains culture across time.

Relation to Thoma’s Broader Work

Although Hans Thoma is often celebrated for his allegorical landscapes and formal seasonal personifications, his figure studies like Old and Young Faun reveal an equally profound preoccupation with the human—or semi-human—condition within nature. Unlike his more overtly symbolic seasonal series, here the mythic veneer is balanced by a strong sense of place and process. The painting stands alongside other nature-infused fantasies—such as his fairy-tale knights and dancing putti—as examples of Thoma’s commitment to blending allegory with Realist observation. It also anticipates later Symbolist explorations of myth and mentorship carried out by artists across Europe, confirming Thoma’s role as a precursor to more fully abstracted mythic imagery.

Reception and Legacy

Exhibited in Munich’s salons of the late 1880s, Old and Young Faun earned praise for its seamless integration of classical myth and authentic nature depiction. Critics admired Thoma’s capacity to treat legendary subjects with approachable intimacy rather than grandiosity. Collectors valued the piece’s decorative charm and psychological depth, cementing Thoma’s reputation as a master of small-scale watercolors. Over subsequent decades, the painting influenced illustrators of fairy tales and children’s books, who drew on its synthesis of pedagogy and enchantment. Today, it remains a beloved artifact of 19th-century German art, celebrated for both its technical prowess and the enduring warmth of its humanistic message.

Conclusion

Hans Thoma’s Old and Young Faun stands as a testament to the power of myth and nature to illuminate universal truths about growth, guidance, and the passage of knowledge. Through balanced composition, nuanced color, and deft brushwork, Thoma captures a fleeting yet profound moment: the elder faun imparting wisdom through music, the youth poised on the threshold of artistic awakening. The surrounding landscape—its waterfall, flora, and grazing flocks—echoes these themes of continuity and nurturing. More than a scene from legend, the painting resonates as a metaphor for all human traditions, reminding viewers that each generation stands on the shoulders of those who came before, and that the simplest gestures of teaching can echo through eternity.