Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

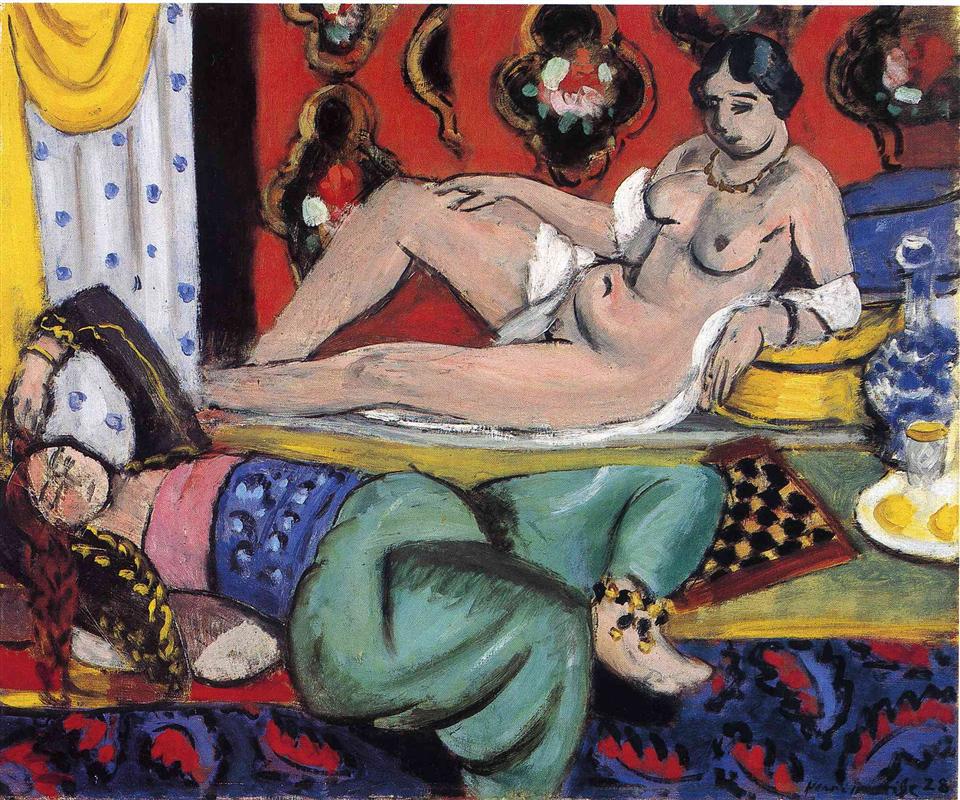

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisques” (1928) compresses an entire world of patterned luxury, quiet conversation, and modern clarity into a single shallow stage. Two women share the room. One, nude except for a white wrap at hip and arm, reclines on a yellow cushion and turns her head toward the viewer with a gaze that is more companionable than theatrical. Below her, another woman lies on a carpet in turquoise trousers and a pink-and-blue bodice, her arm flung behind her head, her anklet resting where turquoise meets the red-and-blue motifs of the rug. A red wall, studded with dark lobed medallions and pale blossoms, pushes forward; a yellow curtain and dotted screen cool the left edge; a blue-glass ewer, a small glass, and two lemons punctuate the right. The tilted chessboard at center acts as the painting’s metronome. Nothing is incidental. Color operates as architecture, pattern as rhythm, contour as breath. The picture offers a lucid demonstration of how the decorative can think.

The Nice Period And A Chamber Of Orchestrated Calm

Painted in the final years of the Nice period, “Odalisques” belongs to Matisse’s sequence of studio interiors in which portable furnishings, screens, and textiles become instruments for testing relations. These rooms are not descriptions of an actual harem; they are portable theaters where light, pose, and pattern can be recomposed until equilibrium is achieved. The hallmark of the Nice years is calm—not the stillness of inertia but a balance secured by clear intervals. In this canvas, calm emerges from the spacing of warm and cool, of curve and grid, of long horizontals and crisp diagonals. The odalisque theme supplies a permissive grammar for drapery, cushions, and jewelry, but the result is not fantasy. It is a modern chamber whose order feels earned.

Composition As A Dialogue Between Two Poses

The composition hinges on the kinship and contrast of the women’s attitudes. The nude at the back forms a long diagonal that runs from left hip to right hand, then tips forward along the forearm toward the blue ewer. Her head rests on a bent arm, giving the diagonal a lyrical lift. In the foreground, the clothed figure forms a compact, low curve parallel to the bottom edge, her body curled like a comma underneath the long sentence of the reclining nude. Between them lies the chessboard, tilted to become a diamond; its grid contradicts the horizontals of cushions and divan and keeps the middle register alert. The yellow cushion is a stabilizing platform for the upper figure, while the dark patterned carpet tethers the foreground figure to the room. The eye travels in loops—curtain to reclining torso to yellow cushion to chessboard to turquoise trousers to rug and up again to the red wall—discovering, with each circuit, fresh balances.

Color As Climate And Architecture

Color builds the space. A wide, saturated field of red sets the room’s temperature, yet it is moderated by substantial blues: the ewer and glass, the sutures of indigo in the patterned carpet, and the cool violets that shadow the reclining body. Yellow appears as both light and matter—the curtain’s folds, the cushion’s volume, the lemon’s rind—and ties the warm wall to the foreground carpet. The clothed model’s turquoise trousers and blue bodice counter the heat with a broad, placid cool. Flesh tones are neither sugary nor harsh; they are a weave of salmon, shell pink, beige, and pearly gray that receives reflections from neighboring hues. Because each color borrows from its neighbors—red glows in the knuckles, blue enters the shadow under the breast, lemon’s yellow glances off the glass rim—the palette breathes. Saturation is high, but harmony stays lucid.

Pattern As Meter, Not Noise

Matisse’s patterns are not ornaments pasted after the fact; they are the painting’s metrical system. The wall’s medallions repeat with dignified cadence, their dark centers surrounded by ochre halos and pale blooms that echo the room’s smaller whites. The carpet’s motifs move faster—red commas swimming in blue—and prevent the foreground from congealing into a bland band. The dotted screen beside the curtain supplies a peppering rhythm, while jewelry beading at ankle and throat adds a delicate upper register. The chessboard’s alternating squares are the most literal meter and the one that best reveals Matisse’s method: a measured alternation of differences that keeps time for the eye.

Contour And The Breathing Edge

Around every color field Matisse lays a living contour—sometimes a seam of black-brown, sometimes a hard contrast of warm against cool—that grants form without imprisoning it. The nude’s shoulder is a single elastic arc; the hand draped on the cushion is simplified into elegant angles and pads; the face is mapped with a few decisive turns around eyelid, nose, and chin. The foreground figure’s trousers are defined not by heavy outlines but by repeated, supple strokes that swell and thin with the fabric’s weight. The ewer’s neck is a confident S-curve. Even the chessboard, for all its geometry, wears slightly wavering edges that declare the presence of the hand. These breathing lines keep the large shapes humane and keep the viewer aware that the decorative surface is also a record of touch.

Light, Shadow, And The Diffusion Of The Riviera

Nice offered Matisse a steady, reflective light that allowed him to keep values moderate so color could assume structural duties. In “Odalisques,” shadows are chromatic: blue-violets under the reclining arm, olive cools beneath the knees of the foreground figure, slate along the yellow cushion’s underside. Highlights are small and exact: a milk-white on the glass, a cool stroke on the hip, lemony glints along jewelry. The result is an image that feels lit from within. Nothing is theatrical; everything is sufficiently illuminated to expose relations between temperatures and shapes.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

The space is deliberately shallow. The red wall behaves like a pinned tapestry just behind the figures; the divan and rug are shelves stacked near the picture plane; objects overlap enough to persuade depth without opening a vista. This productive flatness directs attention to the surface, where meaning is made: where a red meets a blue along a living seam, where the chessboard’s grid interrupts undulation, where a hand rests on yellow and modulates its temperature. The painting asks the viewer not to enter a distant room but to inhabit the surface with the eyes.

Objects As Actors: Ewer, Lemons, Chess

The ensemble of small objects is not anecdotal clutter; each plays a structural role. The ewer’s blue repeats and solidifies the cool chord that runs through trousers and carpet; its vertical form punctuates a composition dominated by horizontal recline. The lemons on the small dish echo the yellow cushion and curtain, keeping that color alive across the width of the painting; their circle also softens the grid’s insistence. The chessboard is the central counterpoint and the most explicit metaphor. Its disciplined alternation of squares echoes Matisse’s own alternation of warm against cool, curve against straight, pattern against plane. The game stands for measured attention—the very tempo the painting requires.

The Two Figures And The Question Of Agency

Matisse’s odalisque imagery always brushes against the history of Orientalism. What distinguishes this canvas is the redistribution of dignity and agency through pose, placement, and the equality of handling. The nude reclines but keeps a steady, unprovocative gaze; the clothed figure claims the foreground with the strong weight of her trousers and the banded force of the carpet. Both share the jewelry’s delicate cadence, and neither is reduced to mere decorative emblem. They exist within a web of relations as equal partners with objects and patterns. The studio fiction clears a space where attention can rest without voyeurism, where seeing becomes an act of pacing and care.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse often conceived painting as music: planes as chords, patterns as tempo, edges as phrasing. In “Odalisques,” the red wall sustains a slow drone; the carpet keeps a sturdy bass line; the chessboard clicks out short, quick notes at the center; the jewelry adds tiny trills; the long line of the reclining body is a legato melody; the curled form of the foreground figure is a lower counter-melody. The eye’s path is guided like a theme with variations. On each repetition, small harmonies appear: a red bloom in a medallion answering a flush at the cheek; a blue in the ewer whispering in the shadow of a knee; a lemon yellow striking the same chord as the cushion’s rim. The picture invites more than a glance—it invites time.

Materials, Touch, And The Differentiation Of Surfaces

The intelligence of touch differentiates materials without describing them pedantically. Skin is knitted from creamy, close strokes; the yellow cushion reads slightly denser, like stuffed fabric under taut cover; the rug is dragged in dry, fibrous passes that let the canvas tooth appear; the curtain hangs in longer, varnished folds; the ewer is made of thinner, translucent blues that carry reflections. Matisse does not hunt for illusion; he arranges enough tactile analogy to make each thing convincing while keeping loyalty to the flat plane.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Odalisques” speaks across Matisse’s work from 1925 to 1928. It shares with “Playing Chess” the tabletop metaphor of measured thought and the company of a blue vessel and lemon-yellow accents. It echoes “Odalisque with a Turkish Chair” in the red medallioned wall and the casual exchange between stripes, curls, and grids, but it alters the balance by placing two figures in contrapuntal poses. Compared with the gridded austerity of “Reclining Odalisque” from the same year, this painting returns to ornamental abundance, showing that Matisse could sustain clarity even in a saturated decorative climate. It also looks forward to the late paper cut-outs in its reliance on large, interlocking, clearly bounded shapes.

Evidence Of Process And The Earned Harmony

Pentimenti and small restatements reveal a search for balance. The border of the chessboard shows repainted red to sharpen its dialogue with the rug; the arc of the reclining arm is reinforced to keep the diagonal crisp; a medallion near the face is softened so it will not compete with the head; the seam where the yellow cushion meets the torso is cooled to prevent merger. These traces prove that the serenity on the surface did not come easy; it is the outcome of tuning intervals until they sang together.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

The room’s mood is intimate, companionable, and alert. The models share a space of ease; objects remain within conversational reach; light is generous but not theatrical. For the viewer the painting offers hospitality: one can settle into the rug’s rhythm, linger at the lemon’s edge, follow the diagonal of the nude and return through the beads to the chessboard’s neat grid. The experience is not primarily narrative. It is a sustained exercise in balanced attention—the very pleasure Matisse sought to provide.

Why The Painting Endures

“Odalisques” endures because it turns difference into cooperation. The hot wall finds its answer in cool trousers and glass; the long recline is stabilized by a compact curl; the grid keeps pattern from drifting; jewelry and small objects bind disparate zones with punctual notes. The canvas teaches a way of seeing in which clarity and sensuality coexist. Its satisfactions are structural—renewable with every look—rather than dependent on novelty.

Conclusion

In “Odalisques,” Matisse compresses the logic of his Nice interiors into a clear and generous harmony. Two bodies, a chessboard, a blue ewer, lemons, cushions, curtain, and a red ornamental wall become actors in a play where color is architecture and pattern is time. The painting is modern not because it rejects decoration but because it redeems it—turning ornament into a grammar for attention. It is a room one returns to for its poise, its warmth, and the way it shows seeing as a gracious, thoughtful act.