Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

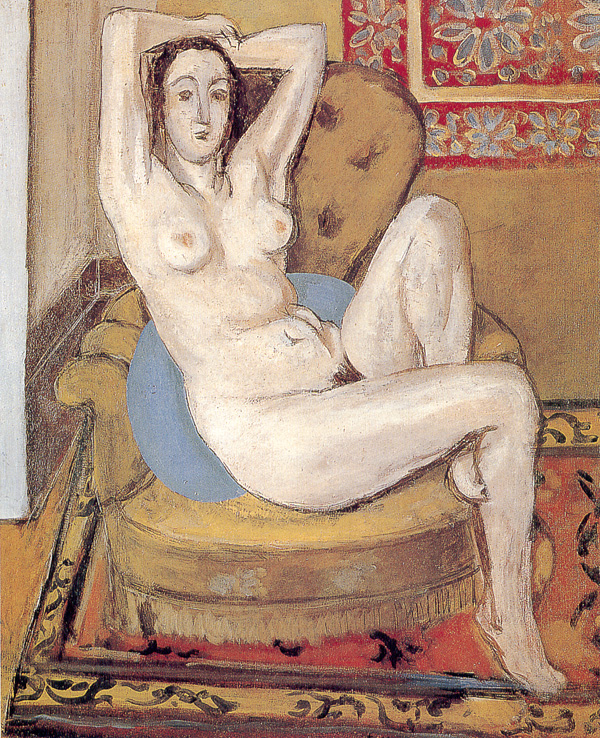

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque with Magnolia” (1924) condenses the artist’s Nice-period vision into a poised interior where a reclining nude, a velvet armchair, and a patterned carpet create an atmosphere of quiet radiance. The odalisque—Matisse’s favorite modern classic—relaxes with one arm lifted above her head, one knee raised, and the other leg extended along the chair. A pale blue round cushion presses into her lower back, a golden chair gathers light around her body, and a floral wall textile at the upper right punctuates the room with ornamental rhythm. Rather than chasing anecdote, Matisse builds a climate of attention in which figure, furniture, fabric, and air share equal dignity. The result is a lucid harmony where the sensation of flesh, the softness of upholstery, and the decorative order of the room are tuned into a single chord.

Historical Context and the Odalisque Theme

“Odalisque with Magnolia” belongs to Matisse’s prolific odalisque cycle of the early 1920s, painted in Nice after his move there in 1917. In this period he replaced the jolt of Fauvism with a modern classicism: ambient Mediterranean light, shallow layered space, and pattern used as architecture. The odalisque, drawn from Orientalist studio theater rather than ethnographic reality, offered him a free stage on which to test those ideas. Reclining or seated nudes could be arranged among textiles, cushions, screens, and carpets, letting color and rhythm carry meaning. Magnolia in the title points less to a botanical study than to the soft, creamy tonality of the figure and to the floral motifs that whisper through the carpet and wall hanging. This odalisque is not a story of the harem; it is a meditation on how a body can belong to a room that has been tuned with tenderness.

Composition: A Calm Geometry of Curves and Frames

The composition is quietly audacious. The oval of the armchair—thickly padded, fringed along the base—acts as a cradle for the figure’s serpentine line. The curve of the chair back echoes the curve of the raised knee; the round blue cushion reinforces the rhythm and pushes the torso forward. The entire arrangement sits on a rectangular carpet whose border, with its looping black ornaments, frames the scene and fixes the perspective to a shallow, intimate stage. A vertical slice of white wall at left and a red-and-green patterned textile at the upper right behave like bookends. Within this nested geometry, the odalisque’s pose—one arm lifted behind the head, the other resting—becomes the slow arc that holds the picture together.

Drawing and Structure: Economy with Authority

Matisse draws with an economy that feels inevitable. The odalisque’s contours are pulled in long, elastic strokes—decisive yet slightly softened—so that the body reads as a chain of full, breathable volumes rather than a diagram of muscles. A few carefully placed shadows describe structure: a cool, compressed hollow beneath the raised knee; a soft notch at the sternum; a gently turning plane along the thigh. The face is simplified to a mask of light with dark, almond eyes and a centered nose; hair is a compact, dark mass that caps the figure and anchors the head against the pale wall. This restraint is not indifference; it is confidence. The painter gives only what the form requires to stand, then lets color and atmosphere complete the sensation.

Color Climate: Magnolia Flesh Against Honeyed Ground

The painting’s palette is a composed chord of magnolia whites, honeyed ochres, powder blue, and muted reds. The figure’s skin is a creamy, magnolia white modulated by pearly grays and faint lilacs, avoiding the pink theatricality that can unbalance a nude. The chair’s upholstery glows in mustard and golden notes that warm the figure without swallowing it. The round blue cushion cools the center, preventing the ochres from becoming oppressive and repeating, in the interior, the coastal blues that underwrite many Nice interiors. At the upper right, a wall textile with brick red and sea-green accents lifts the tonality and ties the composition back to Matisse’s broader decorative vocabulary. There is almost no dead black; even the darkest accents carry chromatic life, allowing warm and cool to circulate rather than clash.

Light Without Theatrics

Nice-period illumination is ambient and benevolent, and “Odalisque with Magnolia” breathes that light. There is no hard spotlight carving the body into fragments. Instead, a general daylight pools across the armchair, slides along the curve of the shoulder, and flickers in the shallow hollow of the abdomen. Shadows are translucent and colored—a soft olive under the thigh, a violet hint along the ribcage—so the picture remains open to the eye. Because the light is even, color and contour can carry the emotional temperature. The effect is serenity: we experience not a single dramatic moment but a sustained climate of rest.

Texture and Touch: A Tactile Scale from Skin to Fringe

One of the painting’s strongest pleasures is its tactile scale. The skin is laid in with smooth, matte passages that receive light softly; the chair’s nap is suggested with broken, fibrous strokes that catch highlights; the carpet’s border is a firmer, more graphic band; the wall textile is a thin, decorative veil. The round cushion is painted more densely, so it reads as a supportive pressure against the lower back. These shifts in pressure and pigment weight are not fussy illusionism; they are the minimum necessary to let each surface assert itself. The nude belongs to the chair because the paint that makes one meets the paint that makes the other with precise, sympathetic decisions.

Pattern as Architecture

Pattern here does the structural work of perspective. The carpet’s border, with its scrolling black motifs on gold, defines the floor plane and pins the chair to it. The wall textile’s rosettes and leaves flatten the upper right into a tapestry, preventing the room from receding too deeply. Even the faint tufting buttons on the chair back form a quiet rhythm that stabilizes the central mass. This is the “democracy of surfaces” Matisse pursued: figure, furniture, and fabric share the plane as equals, each animated by a pattern or contour that contributes to the picture’s tempo.

The Pose: Classical Ease, Modern Honesty

Matisse’s odalisque is recognizably classical—recalling the long tradition from Ingres to Manet—but she is rendered with modern honesty. The lifted arm elongates the torso and opens the ribcage; the raised knee breaks the recline’s monotony and creates a welcoming triangle that keeps the eye inside the picture. Yet nothing is polished to marble. The stomach yields and gathers naturally; the shoulder is a broad, living plane; the foot resting on the carpet curls with believable weight. This blend of classical poise and human softness is central to Matisse’s Nice project: to revitalize the nude without sentimentalizing it.

Space by Layers, Not Vanishing Points

Depth is organized by overlap and temperature rather than strict perspective lines. Foreground: the carpet’s border. Middle: armchair and nude, held to the floor by the chair’s cast shadow and the cushion’s pressure. Rear: the wall textile and the pale slice of wall at left. The short intervals between these layers keep the viewer close, as if standing at the edge of the carpet. This compression preserves the flat truth of the canvas while maintaining a believable room. It also heightens intimacy: the odalisque is not displayed on a stage; she exists in a small, warm air we can almost feel.

Rhythm and the Music of Looking

The painting invites a rhythmic route. Start at the outstretched foot planted on the carpet’s red arabesques. Glide up the shin to the raised knee, across the soft valley of the abdomen, and into the lifted arm’s arc. Drop along the far arm to the cushion’s cool blue, then glide across the upholstered seat to the chair’s fringe. Ascend the backrest with its quiet buttons and re-enter the wall textile’s red and green motif before returning to the face. Each circuit confirms how curves rhyme: foot to knee to shoulder to head; cushion to chair to carpet to wall. Nothing jars; intervals are measured with the calm precision of chamber music.

Magnolia as Motif and Mood

Why “magnolia”? The title points to more than a flower. Magnolia connotes creamy, luminous white, and that is the keynote of this canvas. The body’s magnolia value is set carefully against warmer grounds so it glows without glare. The floral textile at the upper right reads like a memory of magnolia petals within Matisse’s decorative repertoire. Magnolia also implies fragrance and stillness, qualities the room embodies. We are not in the thick air of fantasy; we are in a bright, gently perfumed interior where light rests on skin as lightly as petals.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

Compared with the saturated reds of “Odalisque with a Green Plant and Screen” (1923), this painting works in a quieter key; it trades spectacle for equilibrium. The pale flesh, blue cushion, and golden chair recall the tonal refinements in “Nude Reclining on a Sofa,” yet “Odalisque with Magnolia” compresses the space further and gives pattern a greater architectural role. The face’s masklike simplification and the body’s planar clarity also look forward to the late gouaches découpées, in which figure and ground reduce to essential rhythms. Here, however, those rhythms are breathed into oil and upholstery.

Meaning Through Design

What does “Odalisque with Magnolia” finally propose? That calm is designed. A chair is chosen for its oval embrace; a cushion is placed to set a cool center; a carpet’s border measures the floor; a textile warms the upper register; light is kept even; drawing is economical; color is tuned so warm and cool exchange breath. Within that climate the nude does not pose for seduction but rests as a fact among facts—one presence among others. Matisse’s ethic is not ascetic minimalism or overloaded luxury; it is a balanced hospitality extended to the eye. The painting teaches how a room and a body can be arranged so that attention becomes pleasure.

How to Look, Slowly

Begin at the carpet’s border where black arabesques step like notes along a staff. Let those notes carry you to the foot and up the shin. Pause in the soft pool of the abdomen and feel how the blue cushion cools the heat of ochre upholstery. Trace the lifted arm’s arc and notice how the head sits, masklike, inside it. Wander to the wall textile’s red rosettes, then descend the chair back and fringe to the planted foot again. Repeating this loop, the relations grow clearer: magnolia against gold, curve against frame, pattern against plain. The odalisque is both center and participant; the room is both stage and companion.

Conclusion

“Odalisque with Magnolia” stands as a concise declaration of Matisse’s Nice-period creed. With a limited cast—a reclining nude, a generous chair, a blue cushion, a bordered carpet, a fragment of floral textile—he composes a climate where color breathes, pattern sustains, and drawing says only what is necessary. The magnolia body glows without vanity; the room supports without fuss; the entire surface holds together as a poised harmony. Nearly a century later, the painting still feels fresh because it offers a usable wisdom: arrange relations with care and even the quietest interior will sing.