Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

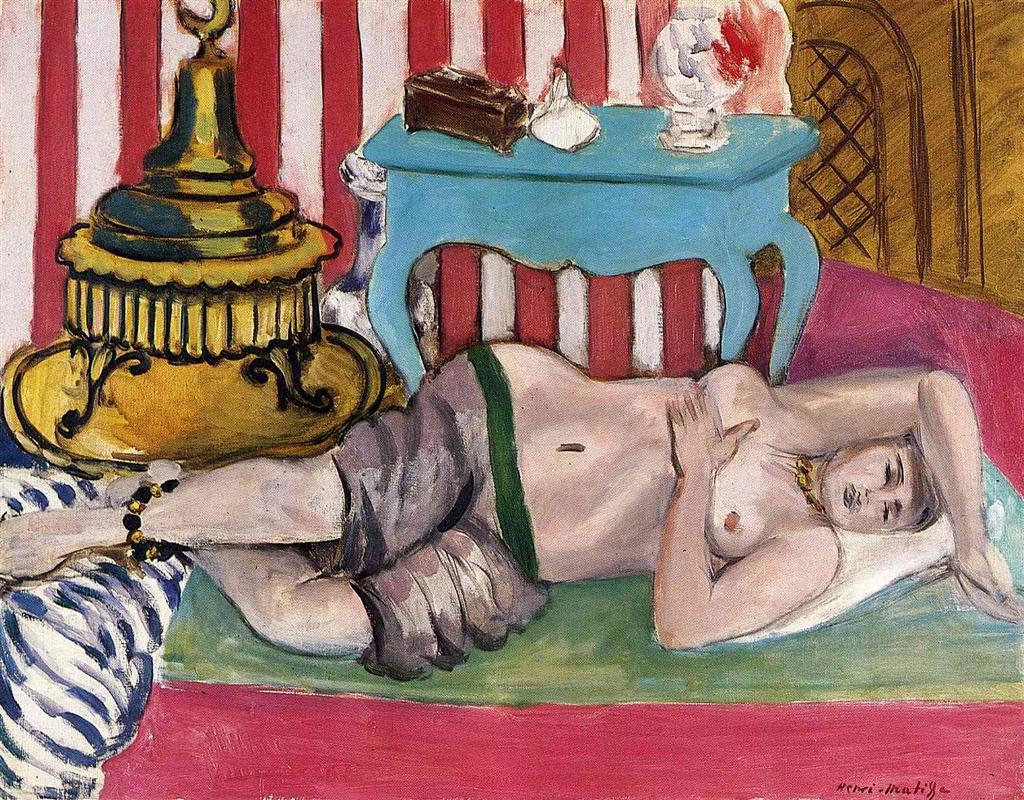

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque with Green Scarf” (1926) crystallizes the decorative intelligence of his Nice period into a playful, precisely balanced interior. A reclining model rests diagonally across a shallow stage, one arm bent under her head and the other laid across her chest. She wears a strand of warm beads, a green sash at the waist, and a small bracelet whose black and gold notes quietly echo the room’s larger motifs. Around her, Matisse orchestrates a theatrical set: a backdrop of red-and-white vertical stripes, a turquoise table topped with small studio objects, a luminous gilt brazier at left whose arabesque feet clutch the floor, and patterned textiles that push forward like painted sound. With just a few elements, he composes a world where color, contour, and pattern carry all the meaning, and where the figure’s relaxation is held in place by an intricate lattice of visual decisions.

The Nice Period And The Recasting Of The Odalisque

The Nice years allowed Matisse to refine a modern classicism based on calm, sustained relations rather than shock. In these interiors, he staged human presence among textiles, flowers, and portable furniture, treating every object as a note in a larger harmony. The odalisque motif—historically burdened by Orientalist fantasy—became his most flexible studio device. It licensed languor and drapery, invited patterned backdrops, and made room for a poised sensuality that need not turn theatrical. In “Odalisque with Green Scarf,” the model’s modern haircut, the ordinary tabletop objects, and the candid handling of paint redirect the theme toward formal exploration. The figure is not an exotic character; she is the calm center around which the visual orchestra tunes itself.

Composition As A Diagonal Stage

Matisse lays out the painting like a chamber theater. The model reclines from right to left across a green ground, her body forming a long diagonal that organizes the entire field. The turquoise table stands behind and above her torso like a proscenium arch; the striped screen beats a vertical time in the background; the gilt vessel at left provides a rounded, monumental counterweight to the elongated figure. The stage is shallow by design: the floor tilts toward us in planes of pink and green, the wall presses forward, and everything is brought near the surface where the eye can register relationships without deep recession. The composition resolves as a triangle woven from diagonal body, vertical stripes, and the table’s uprights, a stable geometry that holds the room’s decorative energy in check.

Color As Architecture And Atmosphere

Color builds the structure and sets the mood. The backdrop’s red-and-white stripes are a measured metronome, intense but not harsh, cut by seams of drawing that keep them hand-made rather than mechanical. The turquoise table vibrates as a cool island among warm registers; its legs bend and flare like stylized waves, and their curves reappear in the gilt brazier’s ornamental feet. The green ground—echoed by the model’s sash—functions as a cooling bed, tuning flesh tones toward peach and rose while protecting them from the stripe’s heat. The brass vessel at left is a deep chord of ochre, bronze, and greenish shadow that stabilizes the palette. Throughout, blacks are used sparingly to articulate edges and give objects a crisp authority, while whites are pearly mixtures that carry reflections of surrounding color.

Pattern And The Discipline Of Ornament

Pattern is never passive decoration in Matisse; it is the grammar that orders the scene. The repeated verticals of the striped screen pace the background with a steady beat. The table’s scalloped apron, the brazier’s ribs and floral supports, and the bracelet’s small alternating beads translate that beat into curving counterphrases. Even the few textiles—the zebra-like blue-and-white cushion at the lower left, the pink plane adjacent to the floor, and the draped skirt at the model’s hips—are used structurally. They lie along the diagonal of the figure, echoing her movement while preventing the green bed from becoming a single, inert block of color. Ornament here is the discipline that makes calm possible.

The Figure’s Silhouette And The Authority Of Line

The odalisque’s presence depends on contour more than on detailed modeling. The jaw is a clean sweep; the shoulder turns in a soft, full arc; the navel is a small, decisive mark; and the hand draped over the breast is rendered with a pared-down geometry that remembers bones beneath skin. The green scarf at the waist is a tight band that cinches the torso and clarifies the body’s axis, while the bracelet and necklace punctuate the limbs like rhythmic accents. Matisse’s line thickens where he wants pressure—along the hip, under the ribcage—and thins over the pillow’s airy edge. This breathing contour makes the body legible against a noisy field without resorting to heavy shading or anatomical rhetoric.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

Light arrives from the upper left and slides across the figure and set with Mediterranean softness. Rather than cast deep shadows, it yields temperature changes: cool notes in the inner arm, warmer planes at the abdomen, a gray-violet turn under the breast. The gilded vessel catches fat highlights and olive shadows that read as reflective metal without descriptive fuss. The turquoise table reflects a thin halo of blue-green onto nearby stripes, knitting object and backdrop. Because the light is diffused rather than theatrical, the painting reads as a sustained chord, not as a snapshot of a dramatic moment.

The Gilded Vessel And The Conversation Of Forms

The large brazen form at the left is more than a prop; it’s a sculptural actor. Its stacked domes and scalloped collar rhyme with the table’s apron and the model’s rounded hip, while its dark legs splay like calligraphic anchors on the floor. Chromatically, the vessel concentrates warm ochres into a single mass that balances the multiple small warms in the figure. Its scale risks dominance, yet Matisse locates it carefully: its dome sits just below the head’s height; its base rests on the same plane as the body; and its right contour is pinched by the turquoise table’s left leg so that the two objects interlock as architecture rather than compete as rivals.

The Tabletop Still Life And The Self-Awareness Of The Studio

On the turquoise table, three small items appear: a dark rectangular box, a pale vessel, and a small shell-like object with a red flare. They function like paused notes—a quiet triad that breaks the stripes and brings the eye to rest before it returns to the diagonal figure. They also declare that this is a painter’s room, a stage of arranging and re-arranging. Matisse was always candid about the studio as theater; these objects stand in for the props and decisions that make the harmony we see.

Flesh, Textile, And The Intelligence Of Touch

The model’s skin is built from soft, layered strokes that toggle between opaque passages and lean scumbles, letting undercolor breathe through. The draped skirt at the hips is stated with confident planes that turn in two or three moves rather than many; whites contain grays and pale yellows so that cloth feels sunlit, not chalky. The zebra cushion’s dark blue lines are dragged over white with a dry brush, leaving broken edges that simulate nap while also insisting on paint. Such tactile variety keeps substance legible—metal, wood, cloth, skin—without surrendering to illusionism.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

The painting honors space while defending the picture plane. The floor is parceled into broad color fields that tilt toward us; the wall’s stripes insist on flatness; and the table and brazier are arranged almost as relief carvings pressed against the background. Yet the reclining figure still feels grounded: the pillow sinks; the arm foreshortens; the green ground wraps the body with shallow perspective. This oscillation between volume and tapestry is quintessential Matisse. It lets viewers inhabit an interior and, simultaneously, read a composition of interlocking forms.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse often likened painting to music, and this image embodies that analogy. The stripes provide a steady meter, the diagonal body a legato melody, the turquoise and gold accents act as bright chords, and the bracelet beads are small syncopations. The viewer’s eye traces an adagio loop: bracelet to brazier to tabletop still life to face to green sash to pillow and back again. With each circuit, new harmonies reveal themselves, such as the green sash’s echo in the bed’s ground, or the red note at the shell repeating the warm blush on the lips.

Orientalism Reconsidered And Redirected

The term “odalisque” brings with it a long history of European projection. Matisse absorbs and reorients that lineage. The relaxed pose, the jewelry, and the drapery nod to the historical motif, yet they serve pictorial ends. The figure’s self-contained expression and the frank, modern drawing resist voyeuristic drama. The room’s exoticism resides largely in pattern and color—features that operate democratically across figure and furniture. In this way the painting translates the old subject into a modern ethic of relation: the decorative is not a mask for fantasy but a method for composing equality among parts.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Odalisque with Green Scarf” converses richly with its neighbors from 1925–1926. It shares with “Odalisque” and “Grey and Yellow Odalisque” the shallow stage and the reclining chord, but pushes ornament’s theatricality further with the bold stripe, the turquoise table, and the monumental brass form. Compared with the pearly, high-key calm of “The Pink Tablecloth” or “Still Life (Bouquet and Compotier),” this canvas is a more extroverted chord, yet it remains exquisitely measured—proof that Matisse could amplify color and pattern without sacrificing poise.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

Despite its saturated palette and baroque props, the painting’s psychological tone is collected. The model’s features are simplified to calm planes; the hand over the chest signals rest rather than self-protection; and the closed eyes translate inwardness rather than absence. As viewers follow the diagonal and re-hear the stripes’ beat, they settle into the same tempo as the room. The painting’s generous calm is not an escape from feeling; it is a way of organizing sensation so that pleasure can be sustained.

Material Presence And Evidence Of Process

Close looking reveals the painting’s honest surface. Edges of stripes are hand-drawn and slightly irregular. A contour at the hip has been moved and softened; a highlight on the brazier has been lowered to sit properly with the table’s value; the turquoise table’s edge shows a thin undergirding of red, a reminder of earlier decisions. These traces of process deepen the harmony rather than disturb it. They show that this balance was earned: calm arrived through revisions, not formula.

Modern Classicism And The Ethics Of Pleasure

Matisse’s Nice-period classicism is not antiquarian; it is a modern ethic. The painting demonstrates that pleasure can be rigorous, that ornament can be structure, and that a human body can appear sensual and dignified at once. Vertical stripes pace the field; diagonals guide it; volumes are reduced to their necessary planes; and color is tuned like an instrument. The result is an image capable of sustaining long, renewing attention.

Why The Painting Endures

The canvas endures because its pleasures are structural and inexhaustible. Each viewing discloses a fresh hinge: the way a black foot of the brazier touches the pink ground and locks the left corner; the echo between the green sash and the bed’s ground; the tiny red flare on the tabletop finding company in the warm blush of lips and nipple; the turquoise table cooling the heat of stripes and flesh. None of these discoveries exhausts the picture, because the harmony that holds them is larger than any one detail.

Conclusion

“Odalisque with Green Scarf” is not merely a reclining figure among enticing objects; it is a complete demonstration of Matisse’s Nice-period language. The painting turns a shallow room into a stage where stripes keep time, a turquoise table cools the chord, a gilded vessel glows like low brass, and a modern odalisque breathes at the center, poised and unhurried. Color is architecture, pattern is structure, contour is breath, and calm is the achievement of many tuned relations. The decorative becomes profound because it is how the painting thinks—by arranging differences so that they hold one another in balance.