Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

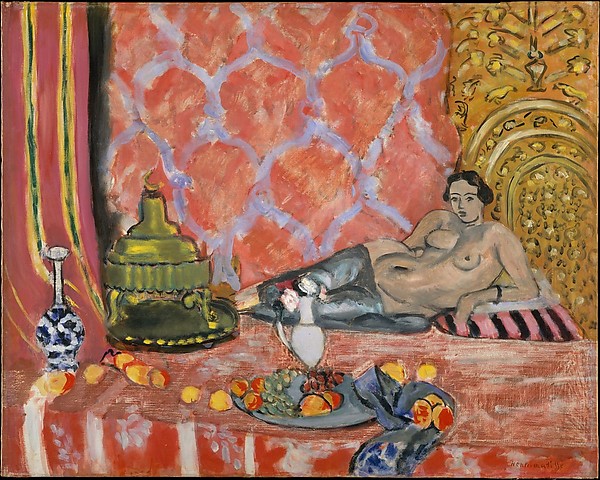

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque with Gray Trousers” (1927) presents the Nice interior as a complete visual chord—equal parts figure, pattern, and still life—held together by the discipline of color. The reclining model lies on a striped cushion in the upper right, her torso rendered in cool, pearly flesh tones and her legs wrapped in gray trousers whose folds gather like soft stone. Across the lower half of the canvas stretches a tablecloth that glows with pinks and corals; on it sit a plate of fruit, a blue ribboned napkin, a garland of lemons, and a slender, blue-and-white bottle. At the left, a large green-gold metal vessel anchors the warm register; at the far right, a gilded niche rises like an architectural reliquary. Behind everything, a coral wall painted with white, scrolling motifs presses forward as a tapestry-like plane. The painting is not a story; it is a poised arrangement of relations, a proof that the decorative can think.

The Nice Period And The Room As Orchestra

By the mid-1920s Matisse had settled into the Nice years’ ethic: treat the studio as a laboratory in which color and pattern are instruments, the model a steady human tempo, and small objects bright notes that complete the chord. The odalisque theme gave him a permissive framework—relaxed poses, abundant textiles, and shining props—without obliging narrative. “Odalisque with Gray Trousers” is exemplary of this approach. Every element plays a role: the figure supplies a long, legible diagonal; the wall sets a steady beat; the metal vessel and the gilded niche gather and distribute warmth; the table objects provide counter-melodies; and the gray trousers—surprisingly modern, almost androgynous—mediate between cool flesh and hot room.

Composition As A Two-Stage Theatre

Matisse divides the canvas into two distinct yet communicating stages. The lower stage is the table: a broad horizontal anchored by a plate set slightly off-center and by a garland of lemons that arcs from left to right like a musical slur. The upper stage is the reclining figure and architectural background: the model’s body stretches from the striped cushion into the middle of the painting, her bent knees pointing toward the green vessel on the left. Between stages, the table edge becomes a proscenium. It does not separate so much as translate—turning the room’s vertical pressure into a horizontal rhythm of fruit, cloth, and reflection. The eye moves naturally from still life to figure and back, discovering that both stages are scored to the same key.

The Coral Wall And Productive Flatness

The wall is a coral-pink field overlaid with thin, white, arabesque motifs, each stroke quick and hand-drawn. It is not a background so much as a breathing skin that presses forward, flattening space and insisting that the action happens on the surface. This productive flatness is fundamental to the Nice period. Matisse lets depth exist—overlaps and cast shadows persuade us that the model reclines behind the table—but he keeps the deep box of perspective on a short leash. The result is a tapestry-like clarity: the viewer reads the room as a pattern of planes whose edges and colors are more meaningful than any illusionistic recess.

The Gilded Niche And The Metal Vessel

Two architectural objects stabilize the composition’s extremes. At right, the gilded niche rises like a decorative shell, its arabesques echoing the wall’s marks yet condensed into sculptural relief. It frames the head and shoulders of the model without imprisoning them, and it concentrates warm yellows that help balance the cooler gray of the trousers. At left, the large metal vessel—domed, footed, and capped by a finial—acts as a companion mass. Its greens and olives are thickened with ochre; highlights lift to honey; shadows slip toward brownish black. The vessel’s rounded silhouette mirrors the odalisque’s bent knees and the swell of the plate below, creating a series of visual rhymes that bind left and right, object and body.

Color As Architecture And Temperature

Color carries the room’s structure. Coral and pinks dominate the wall and tablecloth, setting a warm climate. The metal vessel accumulates that warmth into a dense, reflective mass, while the gilded niche concentrates it into a decorative blaze. Against this heat, Matisse places cool counterweights: the odalisque’s gray trousers, the slate cools of her cushion, the green-tuned shadows in the fruits, and the blue ribboned napkin. The figure’s flesh mediates—pearl, apricot, and cool gray half-tones that borrow warmth from the table and wall while accepting reflections from the grays at her lower half. The small blue-and-white bottle on the left repeats cool accents and punctuates the table’s cadence like a high note. Because each hue borrows slightly from its neighbor, the palette breathes; no color lives in isolation.

The Gray Trousers And Modernizing The Odalisque

The garment at the center of the title is also the hinge of the composition. Traditionally the odalisque is a fantasy of loose silks and bare skin; here, gray trousers bring the subject into a modern vernacular. Their neutrality is not dullness. Matisse makes gray active—cooler next to the figure’s torso, warmer toward the knees, and faintly blue where it picks up the wall’s light. Long, soft folds are described with dark, calligraphic strokes that suggest weight without pedantry. As a block of value, the trousers anchor the body, keep the upper half from dissolving into ornament, and tune the warm field to a cooler key.

The Still Life: Plate, Fruit, Garland, And Bottle

The still life on the table is a precise countermelody. A plate sits like a pale moon ringed by fruit—grapes, citrus slices, and scarlet segments. The lemon garland snakes across the table from left to right, its rhythmic beads echoing the model’s necklace and the vessel’s tiered form. A small, blue ribboned napkin introduces a saturated cool that answers the gray trousers above. The blue-and-white bottle at the far left is both note and metronome: its vertical presence marks the table’s edge while its pattern repeats the room’s vocabulary of curves within a compact silhouette. These objects do not illustrate abundance; they pace the surface and hold the lower register of the composition with bright, tangible notes.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Edge

Matisse’s line is confident without hardness. The model’s shoulders and head are outlined with a soft, dark contour that tightens at the jaw and relaxes along the torso. Fingers and wrist are delivered with a few essential bends; the breast is modeled more by the enclosure of contour and the temperature of adjacent paint than by heavy shading. The trousers’ seams are single strokes that change weight as they turn around the thigh. The vessel’s scallops are rhythmic curves, hand-drawn rather than machined, keeping even the metallic object alive. Contour here is not a prison; it is a porous boundary that lets color expand while remaining legible.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The light filling the scene is the Riviera’s soft diffusion—bouncing, enveloping, and kind to color. There is almost no oppressive black; shadows lean into chromatic relatives: olive under the vessel’s lip, violet along the plate’s edge, cool gray under the model’s arm. Highlights are small and exact: a glint on the finial, a milky shine on grapes, a pale stroke on the shoulder, a quick white on the blue bottle’s neck. Because value contrasts remain moderate, the room’s luminosity arises from color relations rather than theatrical spotlighting. The viewer senses daylight filtered through curtains, not a spotlight staged for drama.

Space, Depth, And The Compression That Clarifies

Depth exists but is compressed. The table pushes toward the viewer; the figure reclines just behind it; the wall presses forward. Overlaps—fruit over plate, forearm on cushion, garland crossing table edge—do the necessary work to persuade space while leaving the surface’s decorative logic intact. This compression clarifies the painting’s true subject: not a narrative scene but the orchestration of planes and temperatures, the spacing of differences that produces calm.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

The room is scored like chamber music. The coral wall beats a steady measure in its repeated white swirls; the lemon garland provides a dotted rhythm; the plate and bottle deliver bright high notes; the vessel and gilded niche carry sustained low chords of warmth; the odalisque’s long diagonal is the melody. The eye moves in loops: bottle to vessel, vessel to knees, knees to face, face to plate, plate along the garland back to the bottle. Each circuit reveals new consonances—a yellow bloom in the niche echoing a lemon bead, a blue ribbon answering the gray crease at the knee, a white highlight repeating in the wall’s motif. The harmony is durable because it is distributed.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

Despite its saturated palette, the painting’s mood is composed. The model looks outward with relaxed, unhurried attention; her body is open yet unperformed. The setting is abundant but not crowded; objects are present as tuned notes rather than props. For the viewer the experience is hospitable: the longer one stays, the more the picture yields—color correspondences, repeated silhouettes, pressure changes in contour, the quiet humor of a lemon bead rolling toward the bottle. The painting invites duration rather than shock.

The Ethics Of Ornament And Modern Classicism

“Odalisque with Gray Trousers” demonstrates Matisse’s ethics of ornament. Pattern is not an exotic mask; it is a method for creating equality among parts. The person, the metalwork, the fruit, and the wall are granted the same clarity of handling. The so-called “decorative” elements do structural labor—spacing, balancing, pacing—so that the figure can inhabit a calm that is earned, not sentimental. This is modern classicism: the reconciliation of strong color with order, of surface pleasure with thought.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

The canvas speaks to neighbors from 1926–1927. It shares the diamond and lattice ambitions of “A Nude Lying on her Back,” but here the wall’s scrolls loosen into cloud-like motifs and the gray trousers introduce a cooler axis. With “Odalisque by the Red Box” it shares the principle of a concentrated accent organizing the field—there a red casket, here a lemon garland and a blue ribbon. Compared with “Harmony in Yellow,” the present painting distributes warmth more broadly across wall and cloth while letting cools arise from garments and small objects. In every case, the constants remain: productive flatness, living contour, and color that behaves as architecture.

Tactile Intelligence And The Evidence Of Process

The canvas records its making. The coral ground shows through the wall’s motifs in places, letting earlier layers flicker. A contour at the knee has been softened from an earlier position; a lemon has been re-sighted to adjust cadence; the vessel’s highlight is re-laid to sit correctly with the plate’s glare. These traces confirm that the calm we sense is not formulaic; it is the consequence of choices, revisions, and small experiments that arrived at equilibrium.

Why The Painting Endures

The picture endures because its satisfactions are structural and renewable. Return to it and a new hinge appears: a faint turquoise reflected in the plate’s rim, a warm echo of the niche on the model’s shoulder, a gray in the trousers aligning with the blue bottle’s shadow, a white swirl in the wall repeating as a highlight on grapes. None of these discoveries closes the work; they extend it. The painting proves endlessly companionable because its order rests on relations that stay interesting as the eye rehearses them.

Conclusion

“Odalisque with Gray Trousers” is a lucid manifesto of Matisse’s Nice-period convictions. A reclining body, a coral wall of living pattern, a shining metal vessel, a gilded niche, and a measured still life are arranged so that color becomes architecture, pattern becomes rhythm, contour becomes breath, and calm becomes an achieved condition. The gray trousers modernize the odalisque and, with their cool neutrality, help the room’s warmer climate find balance. The result is an interior that remains generous to the long gaze—bright, ordered, humane.