Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

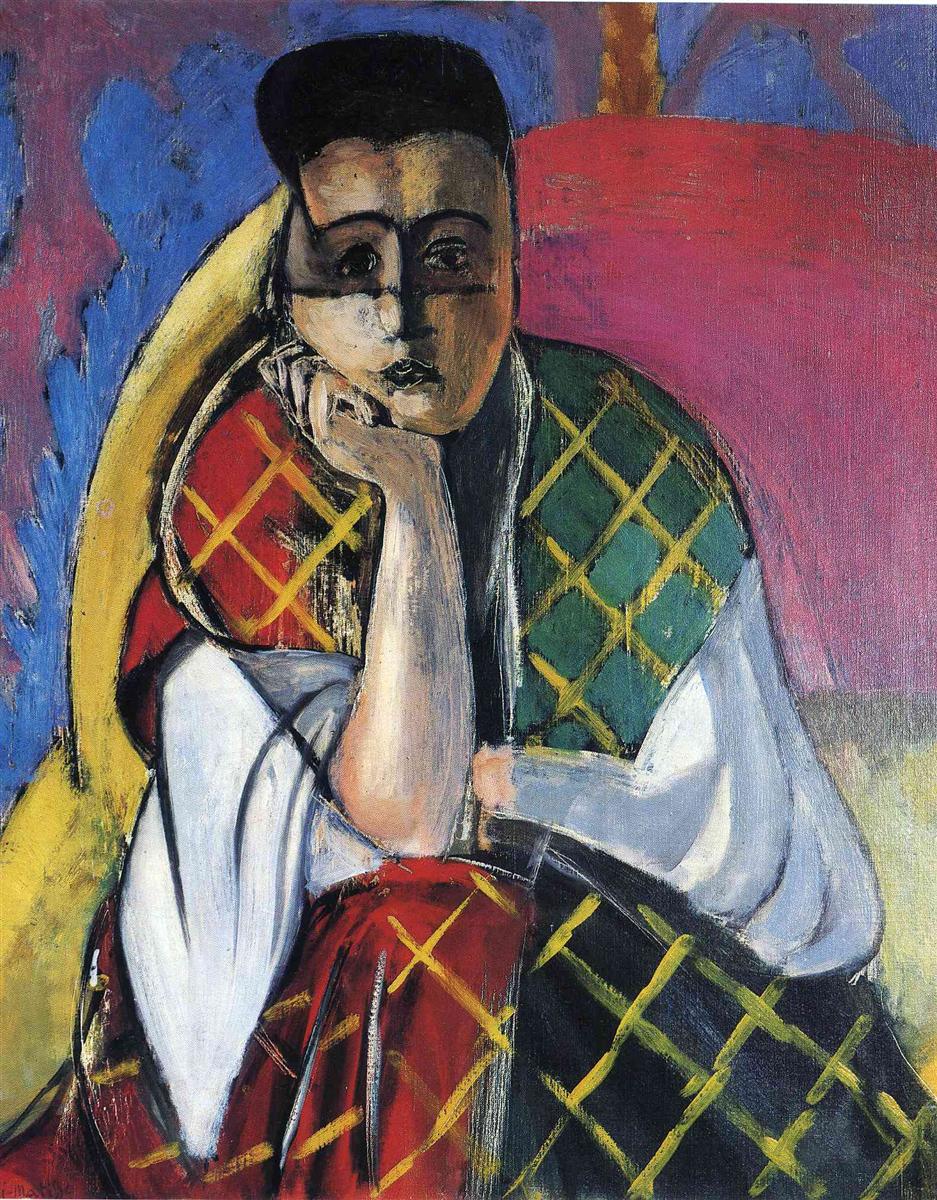

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque with Gray Pants” (1927) is one of the most incisive portraits from his Nice period, a work that compresses the sensual décor of the odalisque studio into an audacious, modernist face-to-face. The model sits close to the picture plane, chin rested on a hand, as if pausing between thoughts. The background fields of cerulean blue and crimson rise like theatrical flats, while a lemon-yellow arc—part armchair, part halo—curves behind the head and shoulder. The garment is a patchwork of diamond lattices in green, red, and black crossed by mustard lines; the sleeves and lower clothing modulate into cool grays and whites. Most striking is the face: asymmetrically modeled with strong umber and charcoal passages that suggest a mask or half-shadow, it fuses serenity and intensity in a single, unforgettable emblem. Rather than an odalisque reclining among textiles, Matisse offers a seated presence whose psychology is built from color architecture, pattern rhythm, and the living authority of contour.

The Nice Period Reconsidered Through a Frontality of Presence

The Nice interiors of the 1920s are often remembered for their languid nudes and saturated ornament. This canvas belongs to that world yet redirects its attention from reclining ease to frontal encounter. The props and textiles are reduced to structural signs: the yellow crescent of the chair, the blue and crimson planes of wall or drapery, the harlequin grids of cloth. By pulling the figure forward and simplifying the set into large, flat fields, Matisse converts decorative abundance into an essential grammar of planes. The odalisque is no longer a distant tableau but a person in the same air as the viewer, a collaboration between sitter and painter that privileges presence over narrative.

Composition as an Engine of Tension and Poise

The composition hinges on a triangular arrangement: the head and hand occupy the apex, the elbows widen the base, and the multicolored garment forms the stabilizing plane. The yellow chair-arc encircles the left shoulder and slips behind the head, both framing and buttressing the pose. Two major color panels—cobalt to the left, magenta to the right—press inward, creating a shallow stage that heightens the immediacy of the gaze. The vertical seam that bisects the lower half—where red turns to black within the garment—acts as a spine that organizes the diagonals of elbow, forearm, and draped cloth. Nothing is casual: each angle either counters or repeats another, building a poised equilibrium from dynamic, asymmetrical parts.

Color as Architecture, Atmosphere, and Psychology

Matisse uses color not to decorate a likeness but to construct it. The dominant chord is a high-contrast triad of blue, red, and yellow, tempered by the cool, nearly metallic grays of the sleeves and lower clothing. The face is modeled with a daring mixture of warm and cool: bone-white flashes on the cheek and nose slide into shadowed browns and graphite blacks around the eyes, while a small, muted red touches the lips. These decisions push the head forward without resorting to naturalistic chiaroscuro; instead, color acts as structural relief. The green and red panels of the vest, crossed by mustard lattices, inject a harlequin vitality that keeps the central mass alive, while the black quadrant at lower right deepens the tonal range and steadies the whole. Because each hue borrows a little from its neighbor—the blue cooling the yellow edge, the red warming the gray sleeve—the palette breathes rather than shouts, and the psychological tone remains thoughtful rather than theatrical.

Pattern as Structural Rhythm Instead of Surface Decoration

The garment’s diamond grids are not ornament laid on top of form; they are the very rhythm by which the body is sensed. Mustard lines cross red, green, and black fields at steady intervals, translating the swelling of cloth over shoulder and lap into a measured beat. Where the grid bends at the elbow, it announces volume; where it approaches the vertical seam near center, it tightens the cadence like a musical accelerando. This patterning also mediates between the stark, flat background panels and the modeled head and hands, letting the figure belong equally to surface and depth.

The Face as Emblem: Mask, Shadow, and Modernity

Few Matisse portraits are as boldly edited as this one. The features are simplified to decisive shapes: an eyebrow rendered as a single, strong arc; the nose as a wedge of light; the mouth a compact, slightly pursed form. The asymmetrical mask—the dark band that swathes eyes and temple—does the work of both shadow and stylization. It suggests time passing across a face, or the memory of movement arrested in paint. This dual identity—mask and living skin—connects the painting to the artist’s interest in non-Western artifacts while remaining rooted in the directness of a studio encounter. The result is not disguise but a modern emblem of thinking presence.

The Hand as Thinking Organ

Resting the chin on the hand is a classical trope, but Matisse reinvents it through touch. The hand is carefully weighted: its back broad, its fingers abbreviated yet articulate, its knuckles mapped by short, pale highlights. This hand is not merely decorative—it is active cognition, a visible hinge between interior thought and outward poise. The gesture anchors the head and also organizes the composition: the forearm makes a vertical that divides the garment’s red and black halves, while the fingers echo the yellow lattice’s small angles. The mind’s inwardness is thus given a structural counterpart in line and plane.

Light, Shadow, and Mediterranean Diffusion

Although the face carries a dramatic value contrast, the rest of the canvas avoids harsh spotlights. Light is diffuse and reflective, typical of the Nice studios: whites bloom rather than glitter; shadows are chromatic—violet in the sleeve creases, olive where the yellow chair returns into space, blue-greys at the garment’s folds. Highlights are placed sparingly: a milky stroke along the hand, a quick, cool note on the nose, small flashes on the lattice intersections. This controlled distribution prevents the image from slipping into melodrama and keeps the attention on color relations and pattern cadence.

Contour and the Authority of the Hand

Matisse’s contour is decisive yet elastic. The arc of the chair is a single, confident sweep; the jawline tightens under the ear and slackens toward the chin; the sleeves are carved by supple, black lines that change pressure as they round the arm. Even where paint is applied thickly, the edges remain alive, never mechanical. The contour’s authority allows color to function as a field rather than as filler; it gives the head its emblematic sharpness while permitting the garment to remain a playground of brushwork and rhythm.

Brushwork and the Tactile Intelligence of Surfaces

The painting registers an array of touches. The blue and magenta panels are laid in broad, scrubbing strokes that let undercolor flicker through; the yellow chair reads with slightly thicker paint, so it catches light like lacquer; the lattice is drawn wet-in-wet, its lines feathering where they cross seams; the face alternates thin scumbles with denser notes so skin feels both atmospheric and present. These varied touches transform flat color into lived substance without sacrificing modern flatness.

Space, Depth, and Productive Flatness

Matisse compresses space without denying volume. The background planes behave like screens pressed near the sitter, but overlaps—hand before cheek, sleeve over lap, chair behind shoulder—supply just enough depth to persuade. This “productive flatness” keeps the eye on the surface where the real drama—color against color, curve against grid, light against mask—occurs. The viewer does not look into a room; the viewer meets a presence on the same pictorial plane.

Rhythm, Music, and the Time of Looking

The canvas is composed like chamber music. The lattice patterns give a steady beat; the blue and magenta panels sustain long chords; the yellow chair provides a counter-melody; and the head-and-hand duet delivers the main theme. The eye makes circuits—chair arc to eyebrow curve, lattice line to finger angle, blue field to gray sleeve—discovering new harmonies on each pass. Because the painting’s rhythm is distributed rather than centralized, it supports prolonged looking: you can reread the intervals the way you replay a movement to hear its inner stitching.

Dialogues within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Odalisque with Gray Pants” converses with several neighbors. It shares the shallow stage and saturated planes of the Nice interiors while moving closer to the language of the later cut-outs, where figure and ground are near-equal colored shapes meeting at exact edges. The harlequin grid recalls earlier interest in patterned textiles but is here distilled into a structural device rather than a descriptive flourish. Compared to the reclining odalisques of 1925–1927, this work is more frontal, more psychological, and bolder in its editing of the face; compared to “Ballet Dancer Seated on a Stool,” it replaces poster-like clarity with a rougher, more introspective tactility. Across these dialogues, constants remain: color as structure, contour as breath, pattern as grammar.

The Ethics of Ornament and Modern Agency

The odalisque motif historically risks exoticism; Matisse counters by distributing dignity evenly across figure and setting. The model’s thinking pose, the sober grays of her clothing, and the frank frontality grant modern agency, while ornament is enlisted not to dazzle but to clarify. The lattice measures the surface; the chair supports the body without staging it; the color fields create a climate for attention. Pleasure here is rigorous—earned through intervals rather than spectacle.

Psychological Tone and Viewer Experience

The work’s mood is reflective. The half-shadowed face, the resting chin, and the large, quiet color fields invite a slower, more contemplative pace of looking. Nothing clamors; everything is awake. As the eye adapts to the painting’s climate, subtle correspondences emerge: a yellow lattice crossing aligning with the highlight on the hand; a blue undertone surfacing in the gray sleeve; a warm echo from the magenta field touching the lips. The experience becomes one of recognition rather than deciphering—relations clarifying themselves through time.

Evidence of Process and the Earned Calm

Close inspection reveals minor adjustments that record the painting’s making: a softened shift in the jaw contour, a lattice line repainted to align with the sleeve fold, a blue scumble allowed to show through at the chair’s edge. These pentimenti do not disturb serenity; they anchor it, reminding us that the harmony we feel is the outcome of trial and revision. The painting’s calm is not formulaic; it has been achieved.

Why the Painting Endures

The canvas endures because its satisfactions are structural and inexhaustible. Each return yields a new hinge—a mustard lattice echoing a yellow in the chair, a cool gray in the sleeve picking up a blue in the background, a black seam speaking to the mouth’s small darkness. The portrait refuses anecdotal closure; instead it offers an environment in which relations remain interesting under repeated attention. In this way, it represents the best of Matisse’s Nice-period ambition: to create rooms—and faces—that the eye can inhabit daily.

Conclusion

“Odalisque with Gray Pants” transforms the odalisque studio into a concentrated encounter with modern presence. Large planes of blue and magenta, a yellow chair-arc, and a harlequin garment build a color architecture in which the head and hand act as the central, thinking motif. Pattern is rhythm; contour is breath; light is chromatic. The result is a portrait that is at once decorative and profound, inviting a long, unhurried gaze that keeps finding new consonances. Few works demonstrate so clearly how Matisse could turn the most economical means into a durable harmony of sensation and thought.