Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

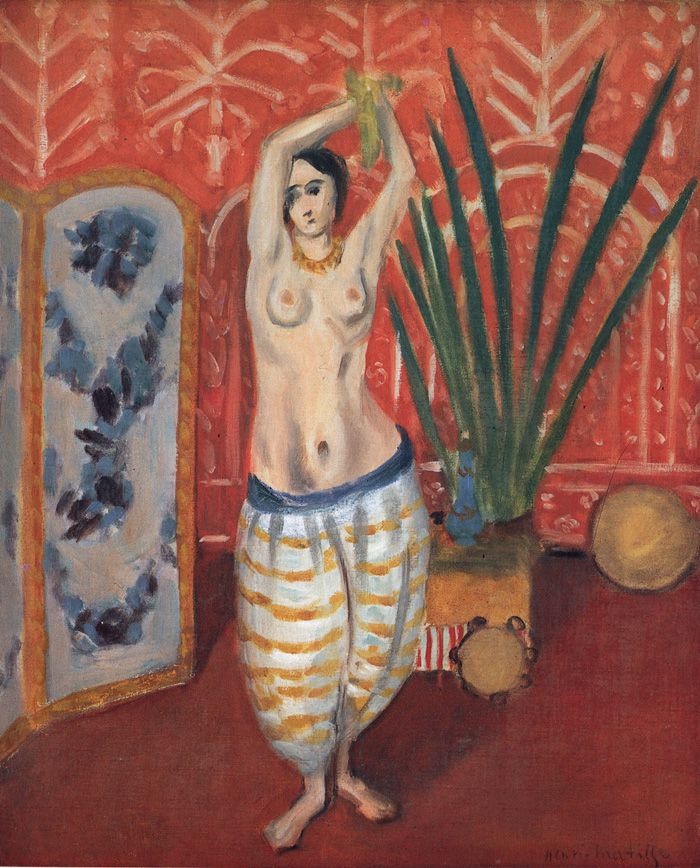

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque with a Green Plant and Screen” (1923) is a radiant statement from his Nice period, where the figure, the room, and the very air are orchestrated into a single rhythm of color and arabesque. The painting presents a half-nude odalisque in loose striped trousers, her arms lifted above her head while a bright green plant rises like a fan behind her and a folding screen punctuates the left edge. Everything is seen through the clarifying light of the Riviera: reds glow without harshness, greens feel newly washed, and the skin breathes in tones of ivory and rose. What appears to be a decorative interior is, in fact, a carefully tuned structure where every shape supports the poise of the body at the center. The work distills Matisse’s conviction that painting can convert sensual experience into calm, lucid order.

Historical Context

In the years following 1917, Matisse made Nice and its Mediterranean light a workshop for a new pictorial equilibrium. The odalisque—an Orientalist subject inherited from Ingres, Delacroix, and nineteenth-century salon painting—became his chosen framework for exploring the nude within embellished interiors. Rather than retell harem fantasies, he used the motif as a pretext to stage the body amid patterned screens, carpets, and plants. By 1923 he had perfected the idiom: the figure is simplified without losing grace, décor becomes an equal partner, and the canvas vibrates with the serenity of well-placed color. This painting sits squarely in that moment, where the Nice pictures fuse the lessons of Fauvist intensity with a newly architectural calm.

Composition as Architecture

The composition hinges on verticals and arches. The odalisque stands slightly off center, her lifted arms forming an acute triangle that locks the torso into place. The red wall, printed with pale botanical arabesques and scalloped arcades, pushes forward like a screen rather than receding like a wall. At left, a folding screen painted with cool blue forms interrupts the red field, counterbalancing the mass of the green plant at right. A low block or table near the plant provides a step-like footing for the still life elements and braces the figure’s stance. Matisse corrals these elements into a stable framework where the eye can circulate without friction: up the arms to the necklace, down the curve of the trousers, along the floor, and back into the fan of leaves.

Color and Atmosphere

Color is both climate and structure. The dominant red of the wall supplies warmth that saturates the entire space. Into this red ocean Matisse sets islands of cooling tones: the pale blues in the screen’s panels, the light gray of the striped trousers, and the glassy green of the plant leaves. The skin is modeled with milk-soft whites broken by gentle roses and slate shadows, never heavy enough to defeat the painting’s luminosity. Against the warm field, a small necklace of yellow flashes like sunlight caught at the throat. Matisse uses these accents to regulate temperature and to prevent the red from overwhelming the figure. The palette is limited but strategic, relying on the resonance between complements—red and green, blue and orange—to keep the surface alive.

The Role of the Green Plant

The green plant is not mere decoration. Its long vertical leaves fan upward, echoing and amplifying the odalisque’s lifted arms. The plant’s upward thrust also answers the downward ballooning mass of the trousers, creating a continuous S-curve that runs from leaf tip to ankle. Chromatically, the saturated green is the painting’s cool anchor; without it, the red wall would be too pervasive and the flesh too faint. The plant also imports a sense of breath and moisture into the room, a hint of gardens and courtyards beyond the studio. It functions as a living arabesque, a botanical line that Matisse can shape and repeat throughout the composition.

The Folding Screen and the Pleasure of Pattern

To the left, the folding screen introduces a second decorative language. Its pale panels, flecked with indigo and blue-black blotches, carry a watery, almost ink-wash feeling that contrasts with the crisp leaf patterns on the red wall. The screen’s gilt frame adds a thin band of warmth that negotiates between the blue interior and the red exterior. This juxtaposition teaches the eye to read pattern as music: one motif offers a low, percussive beat; the other brings a lilting melody. Together they bracket the body like orchestral sections accompanying a soloist.

Costume, Body, and the Dance of the Pose

The odalisque’s striped trousers are central to the painting’s rhythm. Their ballooning volume and alternating bands of warm gold and cool gray set up a gentle undulation that leads the gaze around the lower half of the canvas. The bare torso above is taut by contrast, a column that lengthens as the arms reach overhead. The lifted pose elongates the waist and clarifies the curve of the ribs, while the tilt of the head introduces a note of softness that keeps the figure from appearing rigid. The necklace at the throat punctuates the vertical with a small circular accent. The body is neither idealized nor clinical; it is tuned to the décor, its contours rhyming with neighboring arcs and stripes so that figure and room become one choreography.

Light, Flesh, and the Refusal of Illusion

The painting’s light is ambient and diffuse. There is no single rational source, only a gentle illumination that allows the surface to glow as if from within. Shadows are cool violets and grays rather than browns, and they fall lightly across abdomen, breast, and neck. This handling preserves the flatness of the picture plane while granting the flesh a delicate palpability. Matisse is careful never to overmodel; he leaves transitions open so that the figure can fuse with the surrounding atmosphere. The viewer senses presence without being asked to believe in stage-set depth.

Space as Decorative Field

Conventional perspective is set aside in favor of layered planes. The red wall reads not as distant architecture but as a textile hung close to the figure. The floor is a matte field with minimal recession. The screen turns slightly, suggesting angle, yet it functions more as a color panel than a volumetric object. Matisse is not uninterested in space—he is redefining it. Depth becomes a relationship of colors and intervals rather than of geometric coordinates. This approach allows each surface—wall, screen, plant, body—to retain equal dignity as paint while still organizing a coherent room.

Brushwork and the Discipline of Simplicity

The brushwork appears effortless, but its precision is the result of long refinement. In the wall, quick decorative marks are laid down with a confident wrist, their repetition calibrated so they neither crowd nor thin out. In the plant, a series of loaded strokes describes each leaf in a single gesture. The trousers are built from broad, juicy swathes, the stripes allowed to wobble slightly to maintain the painting’s hand-made pulse. In the torso, paint thins and thickens to suggest delicate passages of bone and muscle. The economy of means is striking: every mark earns its place, and no mark is allowed to become fussy.

Sound, Rhythm, and the Implied Music of the Interior

The tambourines and drum-like discs on the floor imply music. They may be props, but they also signal that the odalisque’s pose partakes of dance. The lifted arms and the gathered trousers recall staged performances, yet the painting’s music is visual, not auditory. Rhythm is woven through the repeated stripes, the leaf fans, the motifs on the wall, and the beats of blue across the screen. The entire image pulses with a tempo that is calm yet lively, like a slow measure kept by a dancer holding a pose between steps.

Orientalism Reframed

The odalisque theme carries a long history of European fantasies about the Eastern harem. Matisse both uses and changes that legacy. He borrows the costume, the textiles, and the decorative exuberance, yet empties the scene of narrative and voyeuristic drama. The model’s expression is inward; her body is treated with the same pictorial respect as the screen and plant. What might have been a colonialist spectacle becomes a study in formal harmony. This does not erase the subject’s historical weight, but it clarifies Matisse’s intent: the painting is less about an exotic Other than about how pattern, color, and the human figure can live together in balance.

Dialogue with Tradition and Sources

Matisse admired Ingres’s odalisques for their sinuous line, but he departs from their porcelain finish by embracing visible brushwork and saturated color. He also draws on Islamic ornament, North African interiors he studied during travels, and the flat patterning of Japanese prints. These influences are not quoted literally; they are metabolized into a language that is his own. The screen’s watery panels might suggest ink painting; the wall’s schematized palms nod to textile design; the trousers’ stripes echo folk garments rather than court costume. The painting’s strength lies in how these references dissolve into a unified pictorial identity.

Comparisons within the Nice Period

Seen alongside “Standing Odalisque, Nude” and other 1923 canvases, this work demonstrates a slightly more theatrical staging. Where the standing nude uses a pink wall to cradle a fully nude figure, here the costume and props set a scene closer to performance. Yet the compositional logic is identical: a vertical figure stabilized by flanking décor, a warm field balanced by cool accents, a compressed space where patterns do the work of architecture. The green plant is this canvas’s distinctive signature, a column of life that offers a counter-melody to the human one.

Emotional Tone and the Ethics of Pleasure

The picture’s feeling is not erotic agitation but poised delight. The body is present and frank, yet the painting’s energy flows through color relations more than through explicit invitation. Pleasure is located in the equilibrium of the whole—the way red bathes the room, the way green cools it, the way blue interrupts and clarifies. Matisse’s oft-quoted wish to offer a restful art finds concrete form here. Rest is not passivity; it is the tension resolved when everything is in its proper place. The painting suggests an ethical relation to beauty grounded in attentiveness, clarity, and grace.

Material Presence and Scale

The canvas retains traces of its making: thin passages where ground peeks through, thicker impastos in the leaves and stripes, edges left open rather than sealed. These decisions let the painting breathe. Even the signature tucked in the lower right corner feels integrated, another dark note tying floor to wall. The objecthood of the picture—its weave, skin, and weight—contributes to its intimacy. One senses a human scale, a work made at arm’s length in a real room with a real model, despite the stylization of every element.

How to Look at the Painting Today

To encounter the canvas now, allow the red to set the temperature of your seeing. Let your eye climb the green leaves and return down the arms to the center. Notice the small necklace catching the warm light and how it keeps the head from floating. Follow the stripes as they wrap the trousers and weigh them against the cool blues of the screen. Attend to the tambourines lying calmly on the floor, reminders that movement can be gathered and stored inside stillness. With each circuit, the work becomes less a scene of exoticism and more an image of pictorial balance achieved through living color.

Conclusion

“Odalisque with a Green Plant and Screen” exemplifies Matisse’s mastery at turning the figure in an interior into a lucid harmony of color, pattern, and line. The painting transforms a charged motif into a modern meditation on equilibrium. The red wall glows like a hearth; the green plant lifts and cools; the blue screen steadies; the body, poised and elongated, holds the entire arrangement in suspension. Through discipline and tenderness, Matisse makes delight feel inevitable. The result is not simply an attractive room with a beautiful model but a lasting demonstration of how painting, at its highest, converts sensual life into enduring form.