Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice Period’s Outdoor Room

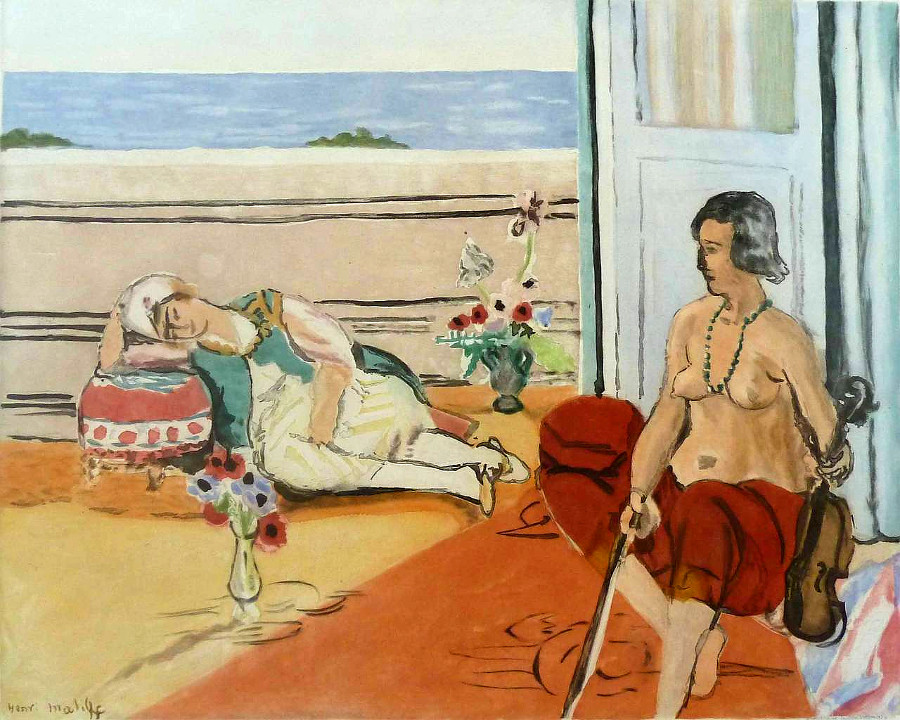

Henri Matisse painted “Odalisque on the Terrace” in 1922, squarely within his Nice period, when he transformed rented hotel rooms and balconies into theaters for light, pattern, and unhurried human presence. The odalisque theme had long served him as a flexible stage: a reclining figure, richly hued textiles, a few carefully placed objects, and a frame that admits Mediterranean air. In this canvas, the interior dissolves into a terrace open to the sea. The composition reads like an outdoor room, a hybrid space where studio order meets coastal brightness. The year is crucial because it marks Matisse’s mature pivot from the shock of Fauvism to a calm intensity built from tuned color chords, calligraphic drawing, and the ethics of ease.

Composition As A Terrace Stage

The painting is organized around a long horizontal band of parapet and sea that spans the picture like a stage backdrop. In front of this band, two figures occupy asymmetric roles. At left a reclining odalisque sleeps against a round cushion, her body arranged in a gentle arc parallel to the horizon. At right a seated woman with a string of green beads holds a violin and bow, her torso upright and her knees angled toward the center. They are separated by a doorway and by a triangular wedge of sunlit carpet that thrusts forward from the lower edge. Small vases of flowers punctuate the middle ground, and the parapet’s rails repeat as stripes that steady the breadth of the view. The composition yields two distinct currents: the horizontal calm of sea and sleeper, and the vertical poise of the musician, with the angular carpet knitting the currents together.

The Dialogue Between Sleeping And Playing

The odalisque and the musician create a quiet narrative of sensation. One figure abandons consciousness to warmth and air; the other holds an instrument that implies sound, discipline, and poised attention. Matisse avoids anecdote. We do not see the bow drawn; the violin is held but not played. The exchange is symbolic rather than literal: rest and readiness, dream and measure, body as resonant chamber and instrument as resonant vessel. The painting’s own structure mirrors this dichotomy, setting flowing curves against firm edges, soft textiles against the crisp parapet line, and the inward turn of sleep against the outward gaze of a seated figure.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Mediterranean Light

Color here is a measured chord keyed to coral orange, pale lemon, minty green, aqua, and rose, punctuated by deeper terracotta and by the cool, steady blues of sea and door. The carpet’s warm field saturates the lower right, an earthly plane where human bodies and objects rest. The oceanic band is a cooler register, built from stacked tones of pale blue and cobalt, horizontally dragged to suggest distance. Between them lies a pale terrace zone that acts like a reflective diaphragm, subtle enough to convey heat without glare. Flowers supply quick reds and violets that keep the palette from slipping into languor, while the green necklace links the musician’s body to the nearby foliage and sea. Rather than maximizing contrast, Matisse prefers adjacency: small temperature shifts within each color family create a climate the eye can inhabit.

Drawing Inside Color And The Authority Of Line

Matisse’s line is calligraphic and decisive, yet it never imprisons color. The contour of the sleeping figure’s back swells and subsides as the brush presses and lifts, conveying both volume and relaxation. The musician’s torso is articulated with a few elastic strokes that imply ribcage and shoulder without pedantry. The rails of the terrace are swift horizontals, lightly quivering, enough to mark distance while admitting shimmer. Interior edges—between carpet and terrace, between wall and door—are softened to avoid slicing the space, maintaining the breathing quality he prized. The violin is delivered with a compact economy: the curve of the bouts and the sweep of the bow establish the instrument’s presence with almost no descriptive chatter.

The Terrace As An Open Room

The terrace functions as Matisse’s favorite motif—the open window—expanded to architectural scale. Instead of a view glimpsed between casements, the entire back of the painting is an aperture. Sea and sky are not extras; they are structural planes that balance the weight of carpet and human flesh. The balustrade is a crucial mediator, maintaining the painting’s equilibrium. Its repeated rails are both safety and rhythm, a human-made order that tempers the limitless field beyond. This device allows Matisse to deliver both immersion in place and clarity of form, the promise of air without the loss of structure.

Ornament And The Grammar Of Objects

Ornament in this picture is sparse but eloquent. Cushions carry simple geometric accents, enough to index softness and craft. The vases of flowers are compact bouquets of red, blue, and white, placed at measured intervals like notes in a melodic line that crosses the terrace. The violin’s dark wood and the beads’ cool green serve as small anchors of material density in a scene otherwise full of light planes and soft fabrics. Even the fold lines in the carpet, marked by slender linear accents, participate in the grammar; they guide the gaze toward the figures and keep the expansive field from floating.

Space Built By Planes, Not By Tricks

Depth is achieved without strict perspective. The carpet wedges forward through a shift in color and texture; the terrace retreats through value lightening and the softening of stroke; the sea recedes by means of horizontal stacking and bluer key. Overlap clarifies relationships—the odalisque is in front of the parapet, which in turn sets the sea at a distance. The doorway’s vertical slab creates a shallow niche for the musician, pressing her forward while acknowledging the room behind her. All of this maintains a shallow, habitable space where decorative order and human presence can share the same plane.

Light As Envelope Rather Than Spotlight

The light is bright yet diffused, likely a coastal midday softened by shade from the building. It lies evenly across bodies and terrace, leaving shadows thin and colored rather than thick and black. On the sleeper, light pales the forehead and the bridge of the nose, then warms into soft cream across shoulder and hip. On the musician, it quietly rounds the breast and collarbone, keeping the form authoritative without weight. Glass in the vases catches small glyphs of white; the sea carries a matte sheen that avoids glitter. Matisse’s light is not drama; it is a continuous, kind clarity that allows color to speak.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

Rhythm binds the composition. Horizontal rails repeat like musical bars, the sea’s strokes pulse between them, and the carpet’s angled edge cuts a syncopation across the beat. Round forms reappear: the odalisque’s cushion, the bouquet heads, the violin’s bouts, the beads. These echoes let the eye keep time as it moves from sleeper to instrument to horizon and back. The absent sound of the violin is replaced by a visual music, an orchestration of intervals that the viewer senses bodily.

The Ethics Of Ease

Matisse’s odalisques often risk being misread as orientalizing fantasy; here the painting’s ethics are evident in its calm. The sleeping figure is neither theatrical nor coy; she inhabits the warmth honestly. The musician’s bare torso is presented without sensationalism; the seated pose is stable and unforced. The scene is hospitable rather than voyeuristic. Bodies are at home with objects and air; the viewer is invited to look long rather than to consume.

The Sea As Emotional Register

Though background in placement, the sea governs mood. Its steady mid-blue cools the picture’s lower heat and extends a sense of deep breath across the width of the canvas. The horizon line, held firmly but softly, is the painting’s calm pulse. By keeping the sea planar and quiet, Matisse lets it act as an emotional regulator. The terrace becomes a threshold not only between interior and exterior but between differing registers of feeling: the intimate warmth of carpet and skin and the measured serenity of ocean.

Material Presence And Tactile Cues

Tactility is delicately delivered. The cushion reveals its woven texture through quick cross-strokes and a slightly chalky highlight; the carpet’s nap is suggested by scumbled passages and thin linear creases; the terrace’s stone is cool and even, handled with pale washes. The violin’s varnish is implied by a simple dark sheen, the beads by small green ovals that catch light. These touches are minimal, yet they anchor the room in bodily experience. One can imagine the heat stored in the floor, the weight of a head on a cushion, the smooth neck of the instrument under a resting hand.

Comparisons Within The Odalisque Series

Compared with the patterned overload of some Nice interiors, this terrace is pared and luminous. Pattern yields to plane; abundance yields to measure. The odalisque appears not amid cascades of fabric but under clear air. The musician’s presence departs from the more common mandolin scenes: the violin’s linear bow and compact body sharpen the composition’s calligraphy, and the seated posture asserts alertness within an atmosphere of rest. The painting stands as a hinge where the lush odalisque idiom meets a broader, Mediterranean spaciousness.

The Viewer’s Path And The Loop Of Attention

The canvas choreographs a loop. The eye enters through the warm carpet, rises to the musician’s beads and bow, crosses the doorway to the sleeping figure’s face, moves along the arc of her body to the floral vase, lifts to the terrace rails and sea, and then returns down the doorframe to the seated figure. Each circuit is slow and satisfying. The loop mirrors the painting’s theme: the alternation between rest and readiness, between dream and measure, between horizontal drift and vertical poise.

The Intelligence Of Omission

Where description would clutter the clarity, Matisse omits. The faces are simplified to a few dark strokes; the flowers are compact notes of color; the parapet’s masonry is suggested rather than built; the ocean carries no whitecaps. This selective telling keeps the scene light and preserves the primacy of relations—carpet to sea, sleeper to musician, cool to warm—over anecdote.

Emotional Weather And Lasting Resonance

The emotional weather is bracing calm. The sea’s steady blue, the terrace’s even light, and the figures’ honest repose produce a mood of expansive ease. The painting endures because it makes a complete world from a few tuned parts and proposes a humane rhythm for looking. It offers a model of attention that is neither passive nor anxious: a viewer can rest in the color and remain alert to the line, can feel the sun and still hear the silent tempo of the violin’s bow.

Conclusion: A Terrace Where Air, Bodies, And Music Meet

“Odalisque on the Terrace” gathers Matisse’s abiding concerns—open thresholds, patterned objects, the dignity of rest, and the balance of color and contour—into a luminous outdoor room. The horizontal sea steadies the scene; the angled carpet energizes it; the sleeping figure and the poised musician dramatize the spectrum between dream and discipline. Nothing is excessive; everything participates. The painting breathes like the day it depicts, a gentle coastal afternoon where air, bodies, flowers, and the possibility of music share a single, lucid space.