Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

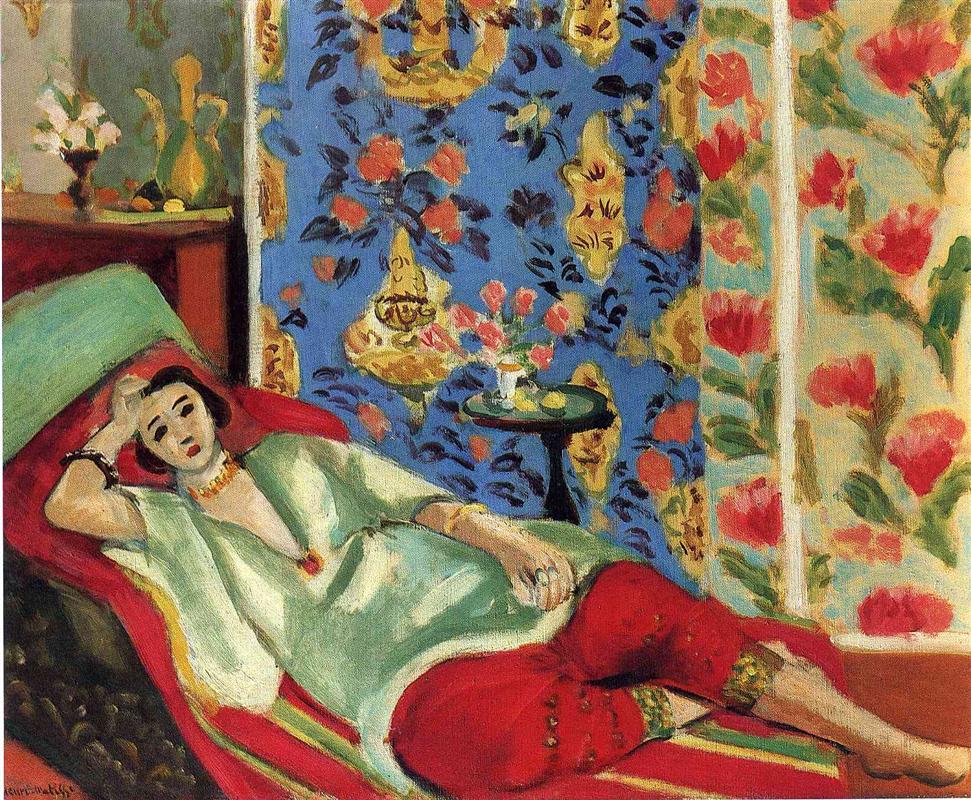

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque in red trousers” is a masterclass in how pattern, color, and pose can turn a quiet interior into a world of heightened sensation. A reclining model—head propped, torso eased into a green silk blouse, legs dressed in ornate red trousers—rests on a low daybed. Around her, the room blossoms: a blue hanging filled with gold and rose motifs, a side panel of pale ground with tulip-like blooms, a crimson throw that slips like a flame along the bolster, and a tiny pedestal table holding a cup and bouquet. Nothing is incidental. Matisse composes each element so that surface decoration becomes the architecture holding the figure in a luminous equilibrium. The result is not a story about the so-called “East,” but a modern meditation on pleasure made legible through paint.

The Nice period and the odalisque as formal catalyst

Created during Matisse’s Nice years, the painting belongs to a group in which the odalisque motif functions as a laboratory for visual relations. Instead of rehearsing orientalist narrative, Matisse uses the reclining model as a hinge linking textiles, furniture, and the geometry of the painted field. The model’s costume is crucial: the red trousers act as the chromatic engine; the sea-green blouse introduces a cooling countertone; the gold jewelry and embroidered cuffs bridge skin and cloth. The studio is curated as a stage where every pattern and hue plays a structural role, letting the painter explore how the “decorative” can carry form.

Composition orchestrated by diagonals and veils

The pose lays out a long diagonal from the model’s forehead to her ankles. That diagonal is buttressed by the daybed’s striping and the red coverlet’s flame-shaped wedge, which slips under the head and accelerates toward the knees. Behind her, Matisse drops a blue hanging that behaves like a vertical curtain, while a pale floral panel at right introduces a second screen that turns just enough to suggest a corner. These two “veils” of pattern do the work of architecture without rigid perspective lines. The tiny round table at center-right is not a mere prop; its circular top breaks the sea of rectangles and leads the eye back to the bouquet and, through it, into the blue field. The composition is a theater of planes, arranged so the viewer can circulate without losing orientation.

Color climate: a four-part chord

Matisse builds the room’s weather from four principal notes. First, saturated red—the trousers and the coverlet—that radiates warmth and energy. Second, Mediterranean blues—chiefly the hanging’s cobalt field—cooling and recessive yet assertive enough to structure the wall. Third, sea-green—the blouse and bolster—that mediates between hot and cool zones, giving the figure an enveloping calm. Fourth, gold and ochre accents—embroidered cuffs, jewelry, motifs in the hanging—that tie the palette to warmth and echo the model’s skin. Skin itself, a pearly rose-grey, is placed as the central moderator, neither bleached nor tanned, allowing the surrounding colors to declare their temperature. Small tertiary notes—a deep bottle green in the pedestal, a pink bouquet, the black hair scarf—keep the chord lively without crowding it.

Pattern as architecture rather than ornament

The blue hanging is built from repeating units: golden medallions, stylized blossoms, dark leaf sprays. Matisse varies pressure and density so the pattern breathes; where the model’s head meets the textile, motifs thin out, preventing conflict with the face. The side panel of tulips is broader in scale and lighter in value, a deliberate contrast that enlarges the room and prevents the back wall from reading as a single slab. Even the daybed’s stripes, a succession of olive, red, and cream lines, are structural: their angle matches the body’s recline and therefore “supports” the pose. Pattern here is not a garnish—it’s the scaffolding upon which figure and space are built.

Drawing that conducts the eye

Matisse’s contour is elastic and musical. Along the figure’s outside edges he keeps the line slightly darker and steadier, preventing the red trousers from spilling into the background. At the face and hand the line thins and sometimes disappears, letting value contrasts do the modelling so the head can float gently against the blue. The blouse is defined by long, sweeping edges; folds are suggested by translucent shifts rather than stitched outlines. In the furnishings, he uses constructive contours sparingly: a heavy seam along the daybed’s edge pins the figure to her support; quick arcs define the pedestal’s ogee profile. The line never cages; it conducts.

Brushwork that keeps air in the room

The surface is frank and varied. Flesh is laid in with soft, opaque planes, then scumbled at the margins to keep transitions breathable. The blue hanging receives a more calligraphic treatment: motifs stamped and dragged, with small halos where wet strokes meet, like glaze catching light on tile. The green blouse is modulated with wider, slightly drier strokes—silky rather than glossy—so it reads as cloth rather than enamel. In the red trousers, pigment is richer, with brief, nervous strokes that describe embroidery without counting stitches. Everywhere the painter stops before detail turns heavy, preserving the lively permeability that is a hallmark of the Nice period.

The figure: poised erotics through relations, not display

Matisse’s sensuality is formal, grounded in juxtapositions. Smooth skin against dense pattern; cool blouse against hot trousers; languor of pose against ornamental bustle of the wall. The model’s gaze is level and unforced, creating a duet rather than a spectacle. The open neckline is echoed by the necklace’s warm ring and the blush at the center of the chest, forming a small chromatic sunrise that holds the upper torso. At the cuffs, narrow green-gold bracelets bridge flesh and fabric; at the ankle, the trousers’ hem repeats that bridge. The erotics here is one of tuned agreements; desire is transmuted into a compositional calm.

The small table and bouquet as chromatic hinge

Placed between the two wall panels, the small round table is almost a punctuation mark. Its dark stem anchors the painting’s middle; its green top picks up the blouse and bolster; the white cup and pink bouquet rest like bright syllables that relate wall to figure. The bouquet is painted with quick, decisive touches—no botany, just lifted color. It repeats the hanging’s roses at a different scale and temperature, knitting the room across space. Because the tabletop is an ellipse, it subtly reorients the eye toward depth without violating the painting’s shallow, staged space.

Space organized by stacked planes

Depth is shallow and deliberate. The daybed occupies a tilted slab; the figure lies across it; the wall comes forward as patterned cloth rather than receding architecture; the right panel turns slightly, creating a hinge plane; the sideboard at left introduces a low horizon of objects. Overlap—not linear perspective—does the spatial work. The figure’s elbow crosses the red coverlet; the table edge breaks the hanging; the bolster pushes in front of the wall. This approach keeps the viewer close to the surface, where color and touch carry the narrative.

Light distributed by value relationships

There is no theatrical spotlight. Illumination is the sum of value agreements. Whites flare where they meet darks: the blouse brightens next to the blue hanging; its hem warms against the red throw. Flesh lightens at the cheek and breast where it faces the room, cools along the forearm that slides into green shade. The hanging appears luminous because small reserves of pale ground sparkle between darker motifs, and because Matisse allows blues of slightly different values to sit side by side. The painting glows not from a single source but from an orchestration of neighbors.

A dialogue with Islamic ornament and the decorative arts

The odalisque suites are deeply indebted to the decorative languages Matisse studied in North Africa and in collections of textiles and ceramics. “Odalisque in red trousers” does not imitate a specific textile; rather, it translates the structural logic of Islamic ornament—repetition with variation, surface continuity, aversion to deep illusion—into painterly terms. The blue hanging’s repeated medallions and leaf clusters remember tiled walls and woven silks, yet remain alive as brushwork. This translation is the secret of the picture’s freshness: the “decorative” is not pasted on; it is the method by which the room coheres.

Kinship and contrast with “Odalisque in Red Culottes”

Compared with the related “Odalisque in Red Culottes,” the present canvas expands the ornamental field and softens the bodily drama. In “Culottes,” a red floor shouts; here, the red is concentrated in trousers and throw, leaving blues and greens to dominate the atmosphere. The figure’s torso in “Culottes” is bare; here, the blouse cools the sensual temperature and intensifies the chromatic conversation. Both paintings pursue the same aim—turning textile, skin, and furniture into a single harmony—but they do so with different weights on the scale.

The viewer’s circuit through the image

The painting invites a reliable path. Many viewers begin at the face—dark hair, red lip, cool cheek—slide down the neckline into the green blouse, cross the bright cuff to the red trousers, follow the embroidered line to the hem and ankle, then climb the red coverlet back toward the head. From there the eye leaps to the bouquet on the round table, then diffuses into the blue hanging’s garden of motifs and finally rests on the pale tulip panel at right before returning to the figure. Each lap yields incidents: a sharp black seam defining the daybed, a burst of yellow inside a hanging medallion, a blue shadow tucked under the wrist, a feathery highlight running along the blouse’s edge. The image is built for repeated looking and never “closes” on a single focal point.

The ethics of ease

Matisse’s famous wish that art function like a “good armchair” is often misunderstood as a plea for prettiness. Here, ease is an achievement of balance. The figure is at leisure without slackness; pattern is abundant without noise; color is saturated yet breathable; drawing is firm yet permissive. The painting proposes a steadier tempo for attention: the eye can linger, compare, return. This is an ethics as much as an aesthetics—an argument that domestic spaces tuned by color and pattern can foster human composure.

Why the image endures

“Odalisque in red trousers” remains memorable because its order feels necessary after a single encounter. A diagonal figure supported by a striped slab; a blue wall of motifs as breathing architecture; a side panel of paler blooms for relief; a red wedge for heat; a round table for hinge; and a palette where flesh settles the chord—every part earns its keep. You can revisit it and find new small perfections: the green glint in a cuff; a tiny orange seed in the hanging; the way a single darker stroke at the jaw firms the head; the precise coolness of the blouse where it slips under the arm. Its pleasures are structural, not anecdotal—hence renewable.

Conclusion

In “Odalisque in red trousers,” Matisse transforms a studio setup into a fully lived pictorial world. Pattern acts as architecture; color sets climate; drawing conducts rather than cages; brushwork keeps air circulating; the figure serves as a serene hinge that binds textiles, furniture, and space. The work reimagines the odalisque not as fantasy but as a rigorous and generous meditation on how looking becomes pleasure. It is modern classicism at human scale—restful, saturated, and inexhaustibly clear.