Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

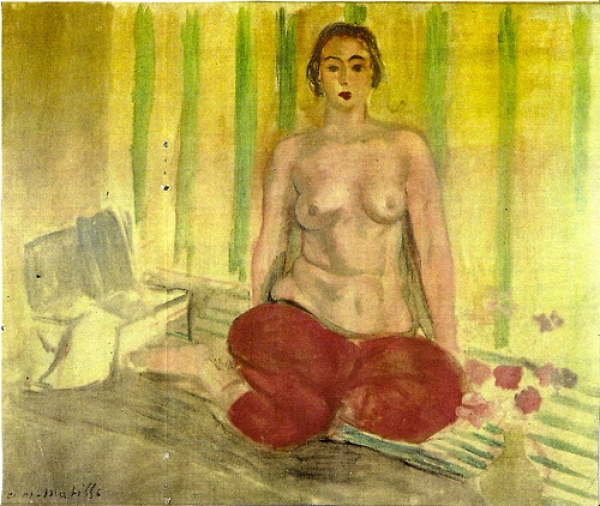

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque in Red Pants” (1925) belongs to the radiant sequence of Nice-period interiors in which he reimagined the odalisque as a vehicle for exploring color, pattern, and the poise of the human figure. The model kneels on a striped mat, torso bare, legs wrapped in voluptuous red trousers, while a thin wash of yellow and green stripes lifts behind her like a screen. To the left sit a small dressing table and an open box or mirror; to the right a simple vase holds a clutch of flowers. The entire scene is modest in incident yet orchestral in sensation. With restrained drawing and a tuned palette, Matisse turns the quiet studio into a chamber of chromatic harmony where the body is both subject and structural axis.

The Nice Period and the Recasting of the Odalisque

After moving to the French Riviera, Matisse found in the luminous climate and manageable interiors a laboratory for testing how color could radiate calm. The odalisque—filtered through a nineteenth-century European fantasy of the harem—offered him a flexible motif: sensuous fabric, relaxed poses, and an excuse for pattern. In the 1920s he stripped the theme of narrative exoticism and reoriented it toward pictorial questions. “Odalisque in Red Pants” is exemplary of this shift. The setting is neither palatial nor descriptive. Instead, a few props and the rhythm of stripes supply an abstract framework within which color and contour can carry the emotional temperature. The model is not a story’s heroine but a collaborator in the painting’s decorative logic.

Composition and the Geometry of Repose

The composition is clarified to essentials. The kneeling figure occupies the foreground like a living column, shoulders squared and head facing forward, arms relaxed along the torso. The triangular sweeps of the red trousers establish a stable base that anchors the rectangle, while the vertical stripes of the wall create a counter-movement that lifts the eye. The arrangement of objects—a low table at left, a vase of blossoms at right—balances the mass of the body without disrupting its primacy. The floor tilts gently forward, a familiar Nice-period device that compresses depth and keeps attention on surface relationships. The painting’s stillness does not feel static; it is the stillness of a pose calculated to keep every part of the rectangle in conversation.

The Chromatic Drama of Red, Yellow, and Green

Color is the central actor. The trousers blaze in saturated reds that modulate toward rose along the upper folds and deepen into wine in the shaded creases. This warmth meets the wall’s lemon yellow suffused with vertical green bands, a pairing that sets up a complementary tension without harshness. The model’s flesh is built from quiet creams and peach washes that absorb surrounding hues, particularly the yellow that halos shoulder and breast. A gray-olive floor cools the palette and prevents it from floating away. Nothing is overly descriptive. Red is not only fabric; it is the painting’s heartbeat. Yellow is not merely paint on plaster; it is ambient light translated into color.

Pattern as Structure Rather Than Decoration

Matisse’s Nice interiors are often called decorative, but in works like this pattern is structural. The vertical wall stripes function like pillars behind the figure, clarifying the space while flattening it just enough to emphasize the canvas surface. The mat’s lateral stripes set up a cross-rhythm that locks the kneeling form in place like a musical chord stabilized by a bass line. Even the flowers operate as patterned clusters—rounded notes of pink and red punctuating the right edge. Ornament here is a method for constructing pictorial order rather than an afterthought.

The Authority of Contour

The figure’s outline is decisive yet soft. Matisse encloses the head, shoulders, and torso with a single, breathing contour that thickens where structure needs emphasis and thins where light dissolves. He rarely carves the body with shadow; instead, he lets transitions ride along the edges of forms. The face is described with economical planes—arched brows, almond eyes, a firm mouth—held together by the logic of the contour rather than by anatomical minuteness. This economy lends the model a masklike calm that suits the painting’s poised mood. Line becomes the armature of sensation.

Flesh, Fabric, and the Material of Paint

Close looking reveals the tactility of Matisse’s brush. Flesh passages are laid with thin, milky veils; here and there a warmer glaze concentrates at the clavicle or along the ribs, letting the figure breathe without heavy modeling. The red trousers, by contrast, gather weight in layered strokes that follow the folds of cloth, producing a velvet-like density. The wall’s stripes are brushed in brisk, semi-transparent bands through which the ground flickers, allowing light to seem embedded in the layer rather than sitting on top. This orchestration of paint quality—thin against thick, matte against softly glossy—animates a composition that otherwise declares its serenity.

Space, Depth, and Productive Ambiguity

The room makes spatial sense but refuses to be measured. The floor recedes, though the plane is shallow; the table at left sits at a slight tilt; the vase rests on the mat without elaborate cast shadow. These controlled distortions keep the eyeline close to the surface, where color intervals do their work. The model inhabits a believable place and a decorative field simultaneously. That ambiguity is not a flaw but a strategy, ensuring that no single illusion overwhelms the harmony of the whole.

The Odalisque Motif Reconsidered

The word “odalisque” carries the historical freight of Orientalism, a European fantasy about non-Western spaces and women. Matisse both inherits and revises that tradition. He retains the relaxed pose and the sumptuous costume, but he strips away voyeuristic narrative and replaces the spectacle of elsewhere with the intimacy of the studio. The figure is not sprawled for display; she sits upright, aware, dignified. The “red pants” are less an ethnographic signal than a chromatic engine. The painting acknowledges the motif’s history while redirecting its energies toward a modern investigation of surface, light, and equilibrium.

The Figure as Axis of Calm

The model’s forward-facing posture gives the painting a quiet authority. Her gaze meets the viewer without drama; her mouth is firm but untroubled. Hands rest along the thighs, neither tense nor slack. The torso is full, with the weight of the body borne by the legs beneath the vivid fabric. This centeredness turns the figure into an axis around which the room’s stripes, props, and colors organize themselves. The calm is not passive; it is composed, like the focused breath a dancer holds between phrases.

Props, Flowers, and the Language of the Studio

On the left a low table or dressing stand and an open box introduce a note of domestic reality. They hint at the model’s preparation without diverting attention from the painting’s formal stakes. On the right a small bouquet in a translucent vase repeats the red of the trousers in a higher, cooler key and answers the green bands of the wall with its stems. These objects are cues in the room’s orchestration of color and shape. They also situate the image within a world of work: the studio as a place where ordinary objects become instruments for pictorial music.

Comparisons Within the Odalisque Series

“Odalisque in Red Pants” converses with companion works from the same years. In “Grey and Yellow Odalisque,” a reclining figure is stretched along a diagonal against a gray field where yellow concentrates in a tray; in “Odalisque with Magnolias,” the body sinks into patterned textiles and a cooler tonality. The present canvas is among the more frontal and simplified, closer to a heraldic emblem than to a narrative interior. Its power lies in the tension between monumentality and tenderness, a duality Matisse also achieved in seated dancers and women at instruments. The continuity across the series is not thematic indulgence but the pursuit of a visual language capable of sustaining varied chords of feeling.

Rhythm and the Musical Analogy

Matisse often likened painting to music, and this work substantiates the analogy. Vertical stripes on the wall establish a measured meter; the mat’s bands offer a counter-rhythm; the red trousers supply sustained, resonant notes; the flowers punctuate like grace notes. The transitions in the flesh read as legato phrases, while the crisp contour of the jaw or the darker fold at the knee adds a moment of accent. To spend time with the painting is to feel its tempo slow the body’s breathing to the calm beat of the studio.

Modern Classicism and the Pursuit of Harmony

Although rooted in everyday materials and a contemporary model, the canvas reaches toward a modern classicism. The frontal pose, the clarity of silhouette, and the controlled palette echo older ideals of balance and gravity, while the loosened brushwork and flattening of space assert twentieth-century candor. Matisse neither quotes antiquity nor rejects it; he distills from it a sense of measure suitable for modern life. The result is a picture that feels stable without stiffness, radiant without agitation.

Psychological Tone and the Viewer’s Experience

The painting’s psychology is one of collected presence. Nothing is hurried, nothing clamorous. The viewer’s gaze rises with the stripes, settles on the steady face, drifts down the arc of the torso to the lush red folds, and then travels sideways to the sober grays of the table or the cool blooms in the vase. This itinerary loops, like a practiced meditation, and with each loop small inflections emerge: a warmer halo on the shoulder, a softening gray along the ribs, a quick brush turn that catches light on a petal. The work rewards patience with an accumulating sense of quiet vitality.

Material Memory and Evidence of Process

Subtle pentimenti animate the surface. At the left shoulder a line appears adjusted and softened; in the wall bands thin washes reveal earlier, cooler underpaint; along the mat a stroke has been dragged to recalibrate a stripe. These traces do not disturb the harmony; they thicken it with time. The viewer senses the painter’s search for exact relations—the point at which the red’s force meets the yellow’s lift, the moment when a contour becomes sufficient and should be left alone. The serenity on view contains the record of decision and revision.

Cultural Context and the Ethics of Pleasure

The Nice period has sometimes been dismissed as decorative retreat, yet paintings like “Odalisque in Red Pants” propose a demanding ethics of pleasure. Harmony is not the absence of thought; it is a practiced discipline. The balance of hot and cool, of surface and space, of frontal monument and intimate studio detail, is calibrated with care. Pleasure arrives as a form of knowledge—knowledge of relationships so tuned that they feel inevitable. In troubled decades between wars, such an art offered not escapism but a lucid alternative to agitation.

Legacy and Afterlives

The lessons of this canvas ripple outward. Designers and painters have returned to its economy—how a few stripes and a single dominant color can organize a room or a picture. The cut-outs of Matisse’s late years are foreshadowed in the emphasis on silhouette and the weightless play between figure and ground. Later artists engaging the figure within patterned fields, from interior painters to contemporary photographers staging chromatic rooms, find in this odalisque a precedent for making harmony feel modern rather than nostalgic. The work’s influence is quiet but persistent because its solutions are structural, not stylistic.

Why the Painting Endures

“Odalisque in Red Pants” endures because it compresses a complex philosophy of art into a simple scene. It shows how the body can be honored without being dramatized, how pattern can build space, how color can think. The trousers burn like a hearth; the wall breathes; the model sits with alert dignity; the studio props keep the image grounded. Everything is necessary, nothing is excessive. The painting’s promise is that attention, patiently applied, can transform ordinary elements into an environment of deep, durable calm.