Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

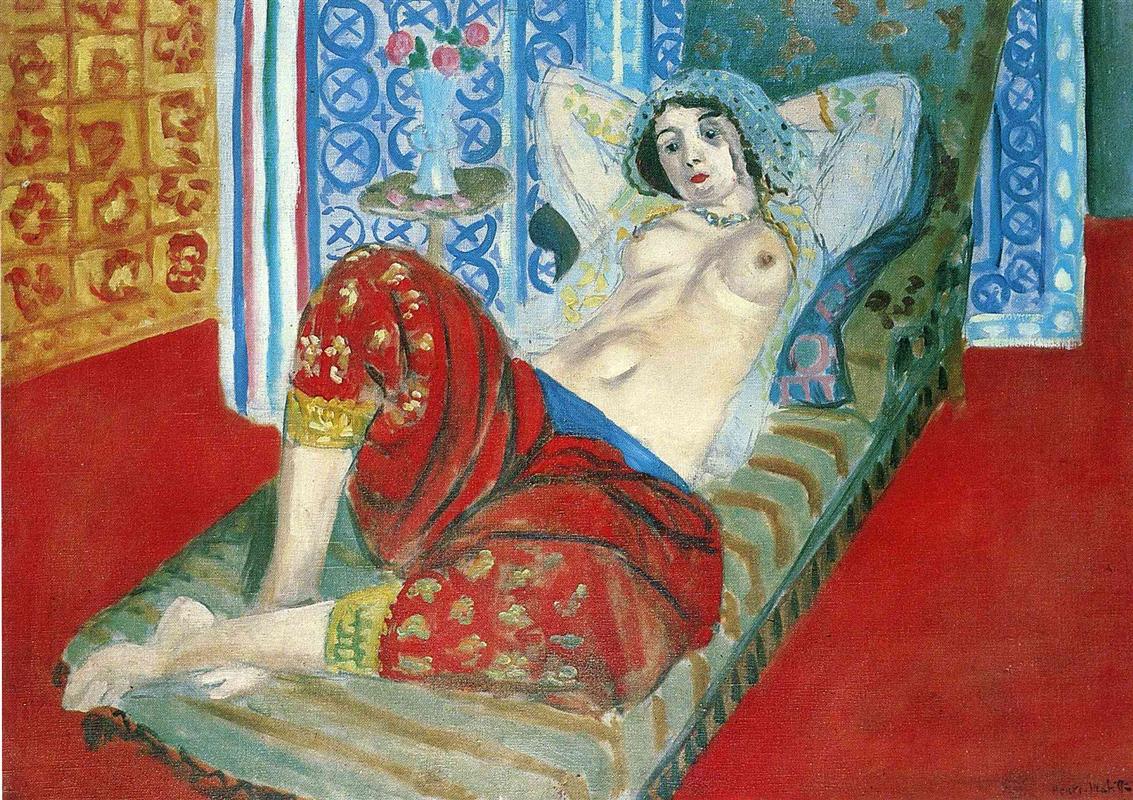

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque in Red Culottes” is one of the most crystalline expressions of his Nice-period language, where color becomes climate, pattern becomes architecture, and the human figure reclines at the center of a carefully tuned decorative world. The composition is immediately arresting: a woman lounges on a low divan, torso bare, head wrapped in a shimmering scarf, her legs draped in vivid red culottes embroidered with golden motifs. Surrounding her, a concert of textiles—striped drapery, blue patterned screen, gilded wall fabric, and olive divan stripes—creates a chamber of harmonies. Rather than stage an anecdote, Matisse builds a mood, sustained through relations of hue, value, line, and touch, until the room feels like a single instrument resonating around a poised body.

The Odalisque Theme Reimagined

Matisse’s Nice paintings often revisit the orientalist odalisque, a subject with a heavy art-historical lineage. In his hands the theme shifts from exotic tale to formal laboratory. The “odalisque” is not a character from a harem narrative but a catalyst that allows him to explore the junction of skin, textile, and light. The red culottes are not costume for its own sake; they are a chromatic engine that activates both the divan’s green stripes and the saturated red ground. The patterned screen is less scenery than scaffolding for the surface, replacing deep space with a breathing wall of motifs. What could be a story becomes a system of visual agreements in which the figure and the room mutually define each other.

Composition: A Diagonal Body and a Theater of Planes

The picture is organized by a strong diagonal that runs from the model’s feet at left across her extended legs and up through her torso to the head. This diagonal locks into a second, slower one formed by the divan’s stripes, so the body appears both supported and propelled by the furniture’s rhythm. A broad red floor occupies the right and lower edges, pushing the divan toward us and acting as a chromatic counterweight to the blue-and-white screen behind. Matisse stages his planes deliberately: red floor as foreground field; olive-striped divan as middle slab; blue patterned wall as shallow background; and a gilded textile at left that seals the space and injects warmth into the upper register. The result is intimacy without confinement—planes press forward, but the eye travels with ease.

The Figure as Hinge Between Pattern and Plain

The model’s pose is languid yet structurally crisp. One forearm props the head, the other rests along the thigh; knees angle upward; feet relax. The torso faces us, planar and luminous, while the legs torque to the side, carving a shallow Z across the picture. Matisse builds the body from large, gently turning planes of warm grey-rose and cool pearl, then clarifies edges with a soft, elastic contour. Flesh is neither anatomically fussy nor generalized into poster flatness; it is toned just enough to hold its own against the loudness of the textiles. The necklace and headscarf introduce small notes of sparkle that keep the face awake in the decorative storm.

Color Climate: Red, Blue, Olive, and Gold

The palette is a four-chord engine. Red saturates the floor and the culottes; blue, across several temperatures, structures the back screen and the shadowed halves of the drapery; olive and khaki inhabit the divan stripes and cushion seams; gold warms the brocade panel at left and trims the culottes’ cuffs. Flesh sits at the center of this chord, a milky, breathing countertone that makes the surrounding colors feel deliberate rather than arbitrary. Matisse avoids excess blending: in the red culottes, for example, warm scarlet abuts cooler crimson and is punched by yellow-gold embroidery; in the blue screen, cobalt circles rest on chalky grounds so pigment vibrates like glazed tile. These juxtapositions produce a climate that is at once saturated and airy.

Pattern as Architecture

Pattern is not garnish; it holds the room upright. The blue screen repeats circles crossed by bars within rectangular panels, establishing a stable grid behind the figure. Because the motifs vary in pressure—some fully loaded, others brushed thin—the screen breathes rather than congeals. The striped curtain at left-right acts like a vertical staff that measures the width of the wall; its red accents echo the culottes and keep the palette braided. The gold textile at far left repeats leaf-and-bloom units that rhyme with the culottes’ embroidery, knitting the space laterally. Under the figure, the divan’s olive stripes angle with the pose, turning pattern into a supporting plane. Each motif does a structural job; none is merely descriptive.

Drawing That Conducts the Eye

Matisse’s contour functions like a conductor’s baton, thickening to anchor, thinning to admit light. Around the torso, the line is soft and occasional, letting flesh breathe into the room. Along the culottes’ outer silhouette, it darkens to keep the saturated red from leaking into the floor. The divan’s edge is described with a single, decisive seam that pins the body to its support. In the patterned wall and curtain, he prefers internal drawing—motif and stripe—over boundary lines, so the periphery dissolves into color rather than being caged by outline. This elastic drawing guides our attention without ever freezing the image.

Brushwork and the Presence of the Hand

The surface is frank. In the red floor, pigment is dragged thinly enough that the weave of the canvas shows through; this porosity keeps the color luminous and stops the foreground from becoming a dead matte. The screen’s shapes are stamped with the brush tip and sometimes overrun, leaving slight halos that feel like light on glazed tile. Flesh is handled with broader, opaque strokes that are then lightly scumbled at the edges; this transition away from the body reinforces the sensation that skin is warm and breathing while textiles are cool and papery. Everywhere, Matisse stops early, allowing the viewer’s eye to complete what the brush proposes.

Skin Against Textile: A Poised Erotics

The painting’s sensuality resides in contrasts rather than explicit detail. Smooth torso against dense pattern; warm planes against cool geometry; yielding flesh against woven stripe. The odalisque’s gaze, direct but unstrained, meets us through the filigree of the room, refusing coyness and melodrama alike. This poised erotics is typical of Matisse: desire is formal, sustained by relations that make looking vivid. The headscarf’s dotted veil both frames and cools the face, tempering the red of the lips and the heat of the culottes. We are invited to see how pleasure in pattern and pleasure in flesh cooperate as parts of the same optical experience.

Space Without Illusionism

Depth is shallow by design. The figure nearly touches the picture plane; the wall is only a few brush-widths behind the divan; the red floor is a slab rather than a receding corridor. Overlap and value step do the spatial work: cushion in front of wall, culotte over leg, hand resting on thigh. Shadows are understated—cooler notes along the torso’s turning planes, a darker seam beneath the knee, small occlusions at the armpit—enough to model form yet unwilling to surrender the clarity of the color fields. The room thus becomes a cultivated surface where near and far are negotiated in pigment rather than plotted by rulers.

Dialogue With Islamic Ornament and the Decorative Arts

Matisse’s engagement with North African ornament and textiles is central here, yet he avoids anthropological pastiche. The blue screen, recalling ceramic or carved wood, is translated into a painter’s syntax—repeating units varied by pressure, transparency, and stop-start rhythm. The striped cotton and the gold brocade are similarly transformed: they are not woven; they are painted, their complexity pared to what the surface can sustain without choking. This translation is crucial to the painting’s integrity; pattern aspires to the condition of paint, not the other way around.

The Red Culottes as Chromatic Engine

The culottes are the composition’s beating heart. Their scale and hue draw us first; their embroidery introduces a second, faster rhythm inside the mass of red; their cuffs, brushed with gold-green, mediate between flesh and fabric. Matisse folds the culottes carefully to generate a mountain of small planes that trap shadows and flash highlights, using red’s full capacity to be both weight and light. Because the culottes rhyme with the red floor yet differ in texture and value, they keep the foreground from feeling empty and stabilize the figure inside the larger field.

The Model’s Gaze and the Viewer’s Path

The odalisque looks outward with a steady, slightly inquisitive expression. Her gaze starts many viewers at the face; from there the circuit flows down the necklace to the breast, along the fold of the culottes to the glowing cuff, across the pale feet to the cushion edge, then back up the diagonals of stripe and screen to the eyes again. Each lap offers incidents: the blue triangle of undergarment that cools the center; a violet half-shadow at the torso’s turn; a tiny rose bouquet echoing the lip color; a thin white glint along the divan seam. The painting is built for repeat viewing—the eye never falls into a dead end.

Light Distributed Through Color Relations

No theatrical spotlight dictates the scene. Illumination arises from calibrated relationships: warm flesh pops because it is surrounded by cool blues and olives; red becomes fully red because of adjacent greens and blues; the screen seems to glow because of small reserves of unpainted ground and pale scumbles among darker marks. Even the highlight on the necklace is a temperature contrast rather than a hard blaze. This distributive light is what gives the painting its restful intensity—bright, but not glaring.

Comparisons Within the Nice Suite

Set beside related works—“Woman on a Rose Divan,” “Moorish Screen,” or “Odalisque with Grey Trousers”—this painting reads as one of the most concise. Some canvases open wide to balconies and sea; others multiply props. Here the set is reduced to essentials: figure, divan, screen, stripe, brocade, vase. That economy clarifies how each element works: the red floor as field, the screen as wall, the culottes as engine, the flesh as mediator. The reduction does not diminish sensuality; it focuses it.

Modern Classicism and the Ethics of Ease

Matisse famously wished for art that would be a “good armchair.” In this painting, ease is not escapism; it is a precise adjustment of forces that lets looking settle without boredom. The figure is at rest but alert; color is saturated but breathable; pattern is dense but legible; drawing is firm but elastic. The calm that results is earned by craft, not drift. In a century roiled by speed and fracture, this kind of sustained poise is a radical proposition.

Why the Image Endures

The canvas stays with us because its order feels inevitable. A diagonal figure, a stabilizing wall of blue pattern, a stabilizing field of red, an olive support, a gilded accent: nothing superfluous, nothing starved. You can return to it and find new small truths—the greenish reflection on a cuff, the slight asymmetry of the wall motif, the way a cushion seam explains the body’s weight, the minute cool edge that defines a shoulder. The painting’s pleasures are renewable because they are structural.

Conclusion

“Odalisque in Red Culottes” shows Matisse at full command of his Nice vocabulary. Pattern is architecture; color is climate; drawing is a conductor; brushwork keeps air in the room; and the human presence is a serene hinge that binds everything together. What might have become a dated orientalist picture is transformed into modern classicism—a living balance of red, blue, olive, and gold, of flesh and textile, of rest and attention. The painting doesn’t recount a story; it sustains a condition, and that condition—poise in color—continues to feel inexhaustibly fresh.