Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice-Period Ideal

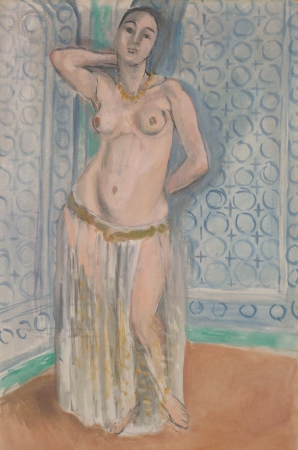

Henri Matisse painted “Odalisque in Blue” in 1922, in the radiant middle of his Nice period. During these years he transformed small hotel rooms and rented apartments along the Côte d’Azur into laboratories where color, light, and the human figure could be tuned into a lucid harmony. The odalisque became his most flexible framework. Rather than reviving nineteenth-century fantasies, Matisse used the theme as a modern grammar: a nude or semi-nude set among patterned screens and gauzy textiles, lit by an even Mediterranean glow, becomes a stage on which planes of color and rhythms of line can breathe. “Odalisque in Blue” distills that program with remarkable economy. A standing figure, draped lightly in a skirt, occupies a corner wrapped in cool patterned walls; the floor is a warm earth tone; jewelry flickers like punctuation. With very few actors, the painting achieves a poised music of light.

Composition As A Corner Stage

The composition is built around a shallow, three-sided corner that functions like a small theater. Two blue walls, patterned with circular latticework, meet behind the model at a soft angle; a low teal baseboard and a rust-colored floor complete the enclosure. Within this simple architecture the figure stands slightly off center, leaning her left shoulder against the wall while her right hand rests on the small of her back. The pose establishes a flowing S-curve from elbow to ankle. The tilted head, lifted breastbone, and crossed feet generate a chain of accents that guide the eye downward and back up again. The skirt’s vertical pleats fall like stage curtains, echoing the room’s blue drapery of pattern. Everything is arranged to keep attention on the long line of the body while the walls steady the space as pale, resonant planes.

The Figure’s Pose And The Poise Of Ease

Matisse’s Nice figures rarely strain. Here the model’s weight settles into the crossed feet as the torso tips gently toward the wall. One arm arcs behind the head, opening the chest; the other disappears to rest on the hip, subtly turning the abdomen. The gesture is neither coy nor theatrical. It is a posture of intelligent ease that allows the painter to explore volumes with unhurried clarity. The face is simplified into clear planes, eyebrows arched in a quietly alert mask; the necklace is a small ring of warm notes that gather the center without competing with the larger rhythms. The whole figure inhabits a tempo of breathing rather than posing.

The Blue Setting As Climate And Structure

The title’s blue is not a single hue but an atmosphere. The walls shift from pale, milky cyan to cool gray blues, over which Matisse lays a lace of circular motifs. These interlacing rings and knots are not decorative chatter; they are a structural grid that turns empty wall into a resilient plane. Their scale suits the figure, large enough to be legible at distance and soft enough to keep the surface from hardening. The blue climate quiets the painting and gives the flesh a place to bloom. A thin teal band near the floor performs the architectural work of a baseboard while adding a deeper, anchoring cool that keeps the lower part of the room from floating.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Calm

The palette is a carefully tuned chord. Cool blues dominate the envelope; the floor contributes a rusty, terracotta warmth; the figure’s flesh modulates between peach and pearly gray; the skirt hangs in whites tinged with blue-violet shadows and pale gold notes. A few precise accents carry disproportionate weight: the necklace and belt glint with small golden strokes that warm the center; the headband’s cool touches align with the room; a narrow greenish cast in the skirt provides a quiet hinge that prevents the composition from dividing into simply warm body versus cool wall. The overall temperature is calm and breathable, a climate of light rather than a contest of contrasts.

Light As A Continuous Mediterranean Veil

The illumination is the Nice period’s signature veil, soft and maritime. It falls without drama, describing volumes by gentle temperature shifts rather than by hard chiaroscuro. Highlights are modest and mostly matte: a soft lift along the shoulder, a higher note on the abdomen, a glimmer on the necklace beads. Shadows are colored, never black. The under-breast turns toward lavender; the side of the torso cools to gray blue; the pleats of the skirt gather thin washes that read as translucency. Because the light is continuous, space and emotion are carried by color; the model seems to inhabit air rather than stand in front of it.

Drawing Inside The Paint

Matisse’s drawing lives in the pressure of the brush. The outline of hip and thigh is elastic, thickening where weight presses and thinning as surfaces turn; the crossed feet are a few decisive planes set at believable angles; the head’s contour, a single assured arc, leaves the face open for a handful of interior signs—arched brows, a firm nose, a small mouth. The circular motifs on the walls are executed with brisk, looping strokes that vary just enough to remain human. What holds the image is not linear description but the way edges of color meet. The figure’s boundary with the wall becomes a live seam where warm and cool exchange breath.

Drapery As Moving Contour

The white skirt, trimmed by a thin belt of gold, is more than costume. It converts anatomy into rhythm. Its pleats drop in long, painterly sighs, dissolving into the floor at the hem; its translucency allows pockets of flesh tone to emerge, creating passages where body and cloth overlap in shared color. A few sharper folds articulate the lift of the knee or the turn of the hip, while broad, wet strokes suggest the weight of fabric without fussy detail. The skirt’s cool whites keep the lower half of the canvas in key with the blue surroundings, balancing the torso’s warmer notes.

Pattern As Architecture, Not Ornament

Pattern saturates the walls but never distracts. The interlaced circles perform the job of architectural molding and can be read like musical time signatures, keeping the beat behind the solo line of the body. Their repetition anchors the eye when the figure’s soft modeling might otherwise dissipate. Pattern recurs discreetly in the jewelry, where small golden ovals echo the wall’s loops on a miniature scale, and in the headband, which places a tempered counterpoint above the face. By absorbing ornament into structure, Matisse turns a potentially exotic set into a modern room of relations.

Space Built By Planes And Overlap

Depth is negotiated with economy. The floor plane is a single warm field that rises to meet the wall at a greenish baseboard. The model overlaps this junction, her crossed feet confirming the corner’s geometry. The wall’s pattern maintains a constant scale as it turns the corner, giving space without resorting to vanishing points. The figure sits squarely within this shallow box, close enough for intimacy, distant enough for the eye to take in the whole. It is a room you can inhabit instantly because the planes are clear and the contacts confident.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The painting’s pleasure lies in rhythm. Circles repeat across the walls; small ovals recur as necklace beads; long verticals appear in skirt pleats and in the wall’s seam; diagonals echo from forearm to crossed shin. Color returns in different registers: blue saturates wall and shadow; gold glints at throat and waist; a warm terracotta hums at the floor while a cooler version washes the abdomen. The eye’s route is reliable—face, necklace, breast, belt, crossed feet, hem, wall pattern, back to face—and every circuit discloses a new syncopation, a slightly cooler edge or a warmer note in the drapery.

Material Presence And Tactile Cues

Although the surface is restrained, it remains tactile. Thin veils of paint on the torso mimic the breath of skin; thicker, wetter drags on the skirt create the sense of cloth with weight; the wall’s pattern shows bristle traces that catch light like the pile of a textile; the floor’s matte warmth reads as chalky plaster. These cues keep the picture anchored in touch while it pursues clarity, preventing the scene from becoming merely decorative.

The Ethics Of Ease And The Absence Of Anecdote

“Odalisque in Blue” carries none of the melodrama often associated with the historical odalisque. The model’s directness, the quiet room, and the absence of props beyond jewelry and cloth produce a frank, contemporary mood. Matisse’s project is not to narrate but to arrange. The painting offers a sustainable form of pleasure: forms tuned to breath, colors calibrated to light, and an attitude of ease that invites looking without fatigue.

Comparisons Within The 1922 Sequence

Placed beside other Nice-period works from the same year, this canvas occupies a distinct register. Compared with the lush interiors crowded by carpets and cushions, its architecture is restrained and planar. Compared with reclining odalisques that depend on sinuous horizontals, it chooses vertical poise, allowing the blue field to assert itself as a full partner to the figure. The palette is gentler than the blazing Fauvist windows of earlier years but more saturated than the pale charcoals Matisse drew in parallel. The painting reads as a midpoint where voluptuous subject and modern clarity meet.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

The picture trains the gaze into a quiet loop. You begin at the head and necklace, follow the curve of the raised arm to the breast, step down through the golden belt, pause at the crossed feet, skim the hem where paint dissolves into floor, and return by way of the wall’s patterned seam to the face. Each pass slows the mind a little more, until the blue field becomes a climate and the small accents—a cooler stroke along the rib, a warmer blush at the hip—assert themselves as events. Time in the painting is not counted by seconds but by breaths.

Why The Painting Still Feels Contemporary

The work remains fresh because it proposes a generous clarity. With a handful of elements—figure, skirt, blue patterned planes, warm floor—Matisse builds a complete world, one that can welcome daily life as easily as museum looking. Designers learn from its grammar of big fields balanced by small accents; painters study how a figure can be modeled by temperature more than contour; viewers adopt its ethic of attention, recognizing that ease can be rigorous and that color can carry meaning without spectacle.

Conclusion: A Clear Accord Of Body, Blue, And Light

“Odalisque in Blue” condenses the Nice period’s best lessons. A standing figure occupies a near-abstract corner; cool blue lattices serve as both pattern and architecture; a pale skirt turns anatomy into rhythm; warm floor and golden jewelry balance the climate. Light arrives as an even veil, and drawing breathes inside paint. Nothing clamors; everything agrees. The result is a room of calm intensity where body and color keep each other company in modern harmony.