Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

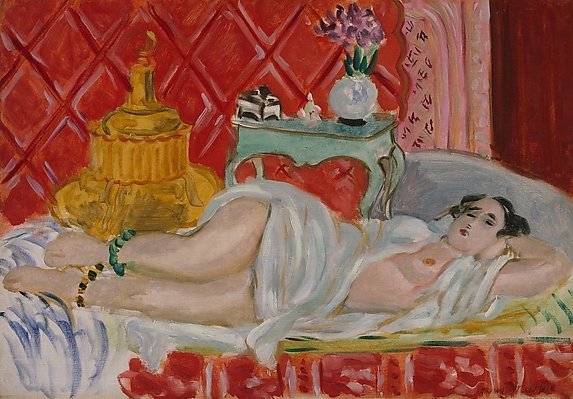

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque, Harmony in Red” (1926) transforms a modest Nice interior into a complete visual chord. A reclining model lies lengthwise across a low divan, a white drape pooling over her body like a soft tidal wash. Behind her, a luxuriant wall of quilted red pushes forward with decisive flatness, while to the left a glowing gilt vessel anchors the composition’s warm register. At the center, a slender turquoise table stages a miniature still life—box, vessel, and a bouquet—whose cool notes keep the room from overheating. The scene is at once intimate and theatrical: the space is shallow, the color is saturated, and every object participates in a carefully tuned rhythm. Matisse’s subject is not an exotic story but the ethics of relation—how pattern, contour, and temperature can coexist so gracefully that the eye settles into calm without ever losing interest.

The Nice Period And The Decorative Ideal

By the mid-1920s Matisse had perfected the poise of his Nice period, steering away from the explosive clashes of Fauvism toward a modern classicism built on measured intervals and long, breathable chords of color. He worked in rooms with shuttered Mediterranean light, surrounding his models with portable screens, textiles, and simple furniture that could be recomposed like phrases in music. The odalisque theme—historically burdened by Orientalist fantasy—offered Matisse a permissive studio framework. It allowed relaxed poses, generous drapery, and patterned surfaces without obliging narrative. “Odalisque, Harmony in Red” exemplifies this approach: the image is saturated with ornament, yet nothing is busy; the model’s presence is quiet but decisive; and the whole is held together by a governing key—red—counterbalanced by turquoise, white, and glints of gold.

Composition As A Reclining Diagonal

The painting’s architecture rests on a powerful diagonal that runs from the lower left, where the figure’s anklet and foot begin the phrase, up through the bent knee and hip, and finally to the pillow at the upper right where her head reclines. This diagonal is the melodic line of the image. It is checked and steadied by verticals and near-verticals: the turquoise table at center, the edge of the wall panel at right, and the discreet pilaster-like seams of the red wall. A series of rounded masses—the gilt vessel, the bouquet, the pillow—punctuate the diagonal with counter-phrases, so the eye is never forced simply across; it loops in slow, satisfying circuits. The drape’s folds repeat the diagonal’s angle in a softer meter, tying figure to setting as if the cloth were a musical accompaniment.

Pattern, Flatness, And The Red Ground

The quilted wall is not mere décor; it is the painting’s atmospheric engine. Each rhombus contains a small highlight that implies padded depth, yet the overall effect remains insistently planar. This patterned field presses forward so strongly that the room reads more like a tapestry than a box in space. Matisse keeps the red from becoming oppressive by inflecting it—crimsons, warm pinks, and terracottas mingle—while the pale seams of the quilting and the cooler gray outlines provide ventilation. The bottom edge repeats the quilt motif at a larger scale, creating a bass line that meets the figure’s flank. Through this disciplined ornament the surface becomes a living plane that carries the painting’s key without drowning the actors on the stage.

Color As Architecture And Temperature

The palette turns on a hot–cool dialogue: saturated red on walls and base, pearly whites and grays in the drapery and sheets, and a beautifully judged turquoise in the table that anchors the cool register. The gilt vessel concentrates warmth into a single, reflective mass, its ochres, bronzes, and olive shadows vibrating against the red behind it. The bouquet advances the cool chord with violet and pink petals set in a white vase; the small dark box on the table offers a compact deep value that keeps the tonal range honest. The model’s flesh is a chord of apricot and pearl, moderated by cool half-tones at the ribs and thigh where reflected color from the drapery and wall participates. Nothing is chemically pure. Whites carry hints of blue or yellow; reds lean warmer or cooler depending on their neighbors. The harmony stays alive because every color borrows slightly from the one beside it.

The Reclining Figure And Modern Presence

Although the title invokes a historical genre, the reclining woman is not a theatrical fantasy. She is a modern subject, composed and collaborative. One arm slips behind her head, opening the chest; the other lies along her torso, fingers quiet, palm turned inward. A simple necklace and anklet mark the body’s axis without turning ostentatious. Her face, rendered with simplified planes—dark hairline, precise brows, a compact mouth—holds the center with calm gravity. Matisse refuses melodramatic expression. Agency comes from poise: the body stabilizes the chromatic abundance around it by offering a clear, readable silhouette and a measured diagonal that orchestrates the room.

The Turquoise Table As Counter-Theme

Placed at the heart of the painting, the turquoise table is more than a prop; it is a structural hinge. Its cool hue counters the red wall, while its slim legs and curved apron add a delicate linear rhythm that echoes, in miniature, the figure’s languid S-curve. On its surface Matisse stages a small still life—a white vase of flowers, a dark box, a small vessel—each object a succinct note. The whites align with the drapery and pillow; the violets and pinks of the bouquet introduce a refrain of coolness; the near-black block quietly grounds the middle register. Because the table straddles the model’s torso, it stitches figure to ground, preventing the body from floating away on cloth and red.

The Gilt Vessel And Concentrated Warmth

At left, a domed, tiered vessel in gold occupies a weighty, almost architectural role. Its silhouette—scalloped rim, splayed feet, pointed finial—reprises motifs that appear elsewhere in the Nice interiors, yet here it is specifically tuned to the red wall. Highlights pick up pinks and whites from the surroundings; shadows slip to olive and deep brown, avoiding dead black. The object’s rounded mass acts as a balancer for the diagonal body: it prevents the eye from simply sliding toward the pillow by offering a gravitational center that also speaks the painting’s warm language fluently. The vessel is not narrative; it is a condensed chord of color and curve.

Drapery, Textile, And The Intelligence Of Touch

Matisse differentiates materials through brushwork rather than illusionistic finish. The sheets are laid with broad, pearly strokes that catch light in soft ridges; the white wrap over the figure is handled as thin, transparent veils that let flesh tones whisper through; the quilt is dragged more thickly, with the paint’s tooth echoing the padded surface; the gilt vessel receives creamier applications, giving it reflective density. This tactile variety tells the hand what the eye sees: cool cotton, airy gauze, warm metal, and painted plaster. Even the small bouquet is a cluster of quick, loaded touches that read as petals because their color and pressure are right, not because each blossom is described.

Drawing And The Breathing Contour

The authority of the painting rests on its drawing. Contours are assertive but never mechanical. The line along the torso tightens over the hip, slackens across the belly, and firms again at the shoulder—like a phrase spoken with emphasis and release. The pillow’s edge is softened so the head sinks plausibly; the breast is modeled with a minimum of planes, kept within a contour that does more work than shading. The table’s legs flare with calligraphic ease, and the gilt vessel’s ellipse is hand-drawn enough to breathe. These living edges keep the surface awake; they let color expand to volume without losing coherence.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

Light arrives not as a spotlight but as an even, Mediterranean wash filtered by shutters and bouncing from pale surfaces. Shadows are chromatic—lavender along the pillow, cool gray beneath the drape, olive on the gilt vessel’s lower tier—so depth is achieved without extinguishing color. Highlights are placed sparingly: a crisp note on the vase, a gleam on metal, a softer white along the shoulder. Because light is treated as a function of color relations rather than as theatrical effect, the painting sustains a calm radiance that lets the viewer linger.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Matisse keeps the space shallow by design. The wall presses forward, the divan tilts toward the viewer, and objects are set nearly in the same visual plane. Yet overlaps—table before torso, vessel before wall, pillow beneath head—provide enough depth to settle the figure in space. This productive flatness concentrates attention where the painting thinks: the surface. It is here that intervals are tuned, edges calibrated, and temperatures balanced. The odalisque is both a person in a room and a shape among shapes, and the dual reading is the Nice period’s special clarity.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse often described his goal in musical terms. The analogy suits this canvas. The quilted wall beats a steady meter, the drapery supplies fluent legato phrases, the turquoise table is a clear, cool chord, and the gilt vessel sounds as a low brass note. The viewer’s gaze follows a composed path: anklet to hip, hip to table, table to bouquet, bouquet to face, face down the drape to the vessel, and across the quilt back to the foot. Each circuit reveals fresh counterpoints—the bouquet’s violet echoing a cool shadow on the belly, a pink seam in the quilt answering a highlight on the vessel, the table’s turquoise reappearing as a faint reflection in the drape’s cool folds. The painting holds attention by pacing it.

Orientalism Reconsidered And Redirected

The odalisque subject carries a long European history of exoticism. Matisse acknowledges the motif—reclining pose, jewelry, drapery, metalwork—yet redirects it. The model’s modern haircut, the studio-like table, and the democratic treatment of every surface displace fantasy. Here the “exotic” is not a cultural other but a formal elsewhere: the ornamental intensity of red, the unusual cool of turquoise, the frankness of patterned flatness. The painting does not stage a harem; it stages a problem of harmony and resolves it with generosity. In this redistribution lies the work’s contemporary ethics.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Odalisque, Harmony in Red” converses with many neighbors. Compared with “Odalisque with Green Scarf,” it replaces the striped backdrop with a quilted one and lets red set the key rather than green. With “Reclining Odalisque” from the same year it shares the low, horizontally stretched pose and the presence of a turquoise table and a brass vessel, but here the color chord is hotter, and the bouquet adds a cool lyric response. Juxtaposed with still lifes such as “The Pink Tablecloth,” it demonstrates the same pearly light and reliance on a few decisive accents to animate calm. Throughout, the consistency is striking: pattern acts as grammar; color builds architecture; contour does quiet but essential work.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

Despite saturated color and close quarters, the psychological tone is collected. The model’s eyes, half-open, register awareness rather than display. Her body is expansive but unforced, the drape modest yet truthful about how it falls. The room feels tended to—objects arranged with care, flowers freshly cut—without tipping into fuss. As the viewer settles into the picture’s tempo, the space becomes hospitable, a chamber where looking is restful but alert. The painting does not demand shock or drama; it invites duration.

Material Presence And Evidence Of Process

Matisse leaves traces of work visible. A contour at the thigh has been moved and softened; a seam in the quilt is repainted to correct its cadence; small pentimenti flicker around the table’s leg. These adjustments communicate without apology that harmony is built, not merely found. The balance we feel—the ability of red to blaze without burning, of white to glow without chalking—is the outcome of revision. Rather than disturb calm, these traces deepen it by revealing the thoughtful labor behind the serenity.

Why The Painting Endures

The canvas endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Return to it and you will hear new correspondences: a cool gray in the pillow recruiting the turquoise of the table; a pink spark in the bouquet aligning with a seam in the quilt; a small green echo of the anklet reflected in the drapery’s shadow; a creamy highlight on the vessel repeating as a petal’s shine. None of these discoveries exhausts the image because its order is spacious. It is built to host attention again and again.

Conclusion

“Odalisque, Harmony in Red” is a compact manifesto of Matisse’s Nice-period art. A reclining figure, a quilted red wall, a turquoise table with flowers, and a gleaming metal form become the means for demonstrating that the decorative can be profound. Color is architecture, pattern is grammar, contour is breath, and calm is a worked achievement. The painting proves that intensity and repose need not be opposites: when intervals are exact, strong hues relax; when the surface is alive, shallow space suffices. The result is an interior that continues to welcome the eye, sustaining a harmony whose warmth and clarity feel perpetually renewed.