Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

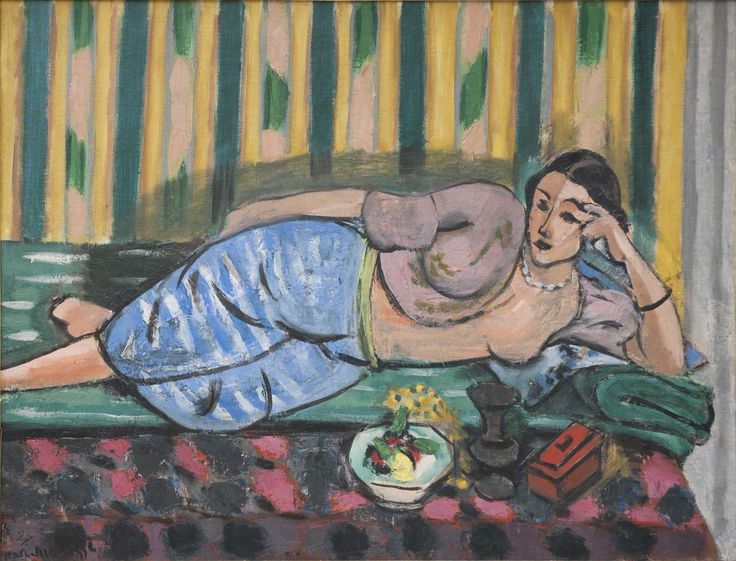

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque by the Red Box” (1927) crystallizes the mature language of his Nice period into a taut, conversational interior. A reclining model stretches along a low divan, head propped on her hand, pearls circling her neck as if to pace the tempo of her breath. A small scarlet casket sits near her hip like a compact exclamation, while a dark, chalice-shaped vessel and a shallow bowl of fruit form a still-life counterpoint at the foot of the couch. Behind her, a striped wall of ochre, green, and teal presses forward as a decorative screen, and a patterned floor advances in rose and black checks. The space is shallow, the color chord deliberate, and the figure’s presence is calm yet alert. Matisse’s aim is not narrative but relation: how pattern and plane, warm and cool, curve and grid can be tuned until they hold one another in a modern, durable harmony.

The Nice Period And The Logic Of Decorative Space

The Nice years transformed Matisse’s earlier audacity into a classicism grounded in interval. Working in luminous Riviera rooms, he treated interiors as laboratories for color, contour, and rhythm, assembling screens, divans, and small objects like musical instruments. “Odalisque by the Red Box” takes full advantage of this studio orchestra. Instead of a deep room, we get a tapestry-like stage where each part is given equal dignity. Pattern is not accessory but structure, and the odalisque motif is a permission slip for languor, textiles, and intimate scale without storytelling obligations. The painting’s intelligence lies in its even-handedness. The model is a poised axis; the props are tuned notes; the surface is where thought becomes visible as color.

Composition As A Reclining Sentence

The composition reads as a single, legible sentence written on a diagonal from lower left to upper right. The line begins with the extended leg, travels through stacked knees and hips, slows across the soft rise of abdomen and breast, and resolves in the tilt of head and hand. Matisse keeps that sentence from running away by placing firm commas along the route: the red box, the dark vessel, and the bowl of fruit break the diagonal into phrases, giving the eye places to pause and restart. The striped wall supplies parallel bars that set the overall meter, while the patterned floor lays a slower bass line that keeps the foreground buoyant. The result is unhurried but never slack. Like a well-paced melody, the figure’s line moves forward while the accompaniment keeps time.

Color As Architecture And Temperature

Color builds the room. The wall’s vertical stripes—ochre warmed toward honey, greens ranging from bottle to sea—establish the dominant field and cool the air. The divan’s deep jade and the pillow’s teal reinforce this cool register and seat the figure convincingly. The red box provides the necessary spark, a saturated counterpoint that concentrates warmth into a small area and prevents the composition from slipping into chill reserve. The model’s flesh is a humane chord of apricot, rose, and pearl gray, slipping cooler where it turns to shadow and borrowing reflections from the nearby greens. The patterned floor alternates rosy tiles with near-black squares, echoing warmth while holding the tonal range. Whites are rarely pure; the blouse’s pale lilac and the pearls’ milky highlights breathe with surrounding color. Blacks are used economically—in hair, eyes, bracelet, and a few contour accents—to set boundaries and tune contrast without heavy-handedness.

The Red Box And The Discipline Of A Small Accent

Matisse’s title foregrounds the red box because it does crucial structural work. Its compact rectangle interrupts the long diagonal of the body, acts as a hinge between still life and figure, and folds a high-chroma warm into the largely cool chord. Its geometry counters the organic sweep of the pose and the curving silhouette of the chalice form nearby. Because the box is small, it gathers attention without stealing the scene; because it is red, it memorably signs the harmony. Remove it and the painting slackens. With it, the chord tightens and the eye’s route is punctuated exactly where it should be.

Pattern As Structural Rhythm Rather Than Ornament

The striped wall and checkerlike floor are the painting’s metronomes. The wall’s verticals set a measured beat behind the figure, their varying widths and imperfect, hand-drawn edges keeping the tempo human rather than mechanical. The floor’s rose-and-black grid moves at a slower pace, tilting toward the viewer and creating a visual pedal tone beneath the divan. These patterns do not sit behind the action; they are the action. They clarify planes, space intervals, and keep the surface alive without recourse to deep perspective. Pattern here is grammar, and the sentence it writes is one of poise.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Edge

Matisse’s contour grants the figure authority. Lines swell and thin as forms turn: the upper arm tightens near the elbow, slackens across the forearm, and asserts itself again at the wrist. The torso’s long curve is set down with an unbroken assurance that allows color to carry most of the modeling. The trousers are described by a few black calligraphic strokes across cool blue that hint at folds while respecting the flatness of the plane. The still-life objects are equally frank. The chalice is a robust silhouette given volume by a couple of judicious half-tones; the bowl is an ellipse warm with fruit and cool where it reflects surrounding green. These living edges let every part breathe and keep the surface harmonized.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The light is the Riviera’s soft diffusion, bouncing off walls and textiles rather than spotlighting the figure. Shadows are chromatic—violets in the blouse’s folds, olive along the divan’s edges, cool gray along the flank—and they transition gently so color can do the shaping. Highlights are small and targeted: a milky glint on pearls, a pale flicker on the lip, a cool stroke along the bowl’s rim. Because light is treated as relation, not effect, the image radiates quietly. It invites long looking rather than theatrical surprise.

The Figure’s Presence And Modern Agency

Although the odalisque theme carries a history of exoticism, Matisse writes a modern presence. The model’s head rests on her hand with an inward, conversational intelligence; her gaze is private rather than performative. The blouse slips and reveals, but its lilac coolness resists melodrama, and the strand of pearls encircles the neck with a rhythm that repeats in the striped wall. Bare forearms and ankles ground the pose without affectation. Agency arises from composure. The figure is not a fantasy ornamented by props; she is the central interval that coordinates room, objects, and pattern.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Space is shallow by design. The wall presses forward as a striped curtain, the divan tilts up, and the floor rises like a stage. Yet overlaps and value changes give enough depth to settle the figure: the arm in front of the torso, the leg crossing the cushion, the box casting a muted shadow. This productive flatness keeps attention on the surface where color and contour operate. It also anticipates the logic of Matisse’s later cut-outs, in which figure and ground negotiate as flat, interlocking shapes whose edges do the expressive work.

The Still Life As Countermelody

At the foot of the divan, the dark chalice, the small bowl of fruit, and the red box form a tight ensemble that answers the figure’s long phrase. The chalice holds the deepest value in the painting, anchoring the tonal scale; the bowl brings cool ceramic whites and citrus notes that echo the wall’s yellows; the box, as argued, contributes a concentrated warmth. Their relative sizes and spacing are exact, creating a counter-melody that keeps the lower register articulate. They are not anecdotes. They are measures that balance the score.

Tactile Intelligence And The Reality Of Paint

Material differences are conveyed through touch. The blouse is laid in airy, scumbled layers that let undercolor whisper, so its transparency feels true. The trousers receive broader, creamier strokes that imply nap and weight. The divan’s green is dragged with enough resistance that the weave of canvas suggests textile grain. The wall stripes are brushed in long pulls, their edges breathing in and out where the bristles stray. The red box is tighter, flatter, and more enamel-like, which suits its role as a crisp, geometric accent. These varied touches keep the decorative idea grounded in the material fact of paint.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse’s oft-invoked musical analogy clarifies how to see the picture. The wall’s verticals are the steady meter; the floor’s grid is a slower ostinato; the figure’s diagonal is the main melody; and the still life gives short, answering motifs. The eye follows a composed route: from the extended foot across the blue trousers to the pearls, down the forearm to the red box, across the chalice to the bowl, and back up through the stripes to the face. Each circuit reveals new consonances: a yellow stripe rhyming with lemons in the bowl, a cool shadow recruiting a bottle-green band, a pearl glint finding echo on the bowl’s rim. The harmony is layered enough to reward repeat listening with the eyes.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Odalisque by the Red Box” speaks to neighbors from 1925–1927. It shares with “Odalisque, Harmony in Red” the reclining pose and the strategy of a dominant color field countered by small, decisive accents, though here the key leans cooler and the accent is a single red rectangle rather than a whole wall. It converses with “Reclining Odalisque” against a diamond background by trading geometric wall pattern for stripes and by emphasizing a more intimate still life. It also foreshadows the cut-outs, where silhouettes lock together and small chromatic sparks keep large fields alive. Across these dialogues, the constant is Matisse’s conviction that the decorative can carry thinking.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

The psychological register is thoughtful and domestic rather than theatrical. The model appears mid-reverie, the hand at the temple a natural counterweight to the reclining line. The red box and bowl feel like reachable objects, not stage props. The room is hospitable; its patterns are assertive but not oppressive; its light is steady. For the viewer, the experience is one of settling into a climate where perception slows. You feel the surface’s tactility, the measured transitions of color, the gentle persuasion of the diagonal, until calm emerges as a worked, repeatable condition.

Evidence Of Process And The Earned Harmony

Small pentimenti confirm the search that produced the calm. A contour along the thigh appears softened from an earlier position; a stripe in the wall is nudged to better align with the shoulder; a dark accent near the chalice has been cooled. These traces are not distractions. They are the history of decisions by which the intervals were tuned. The final chord—cool greens, orderly stripes, a poised body, one brilliant red—rings true because it is earned.

Why The Painting Endures

The work endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Each viewing yields a new hinge: a pearl picking up a lemon’s color, a blue trouser shadow aligning with a teal stripe, a pink tile balancing the lip, a thin black drawing stroke echoing the bracelet. The painting never resolves to a single takeaway; it supports many small consonances under one large, lucid chord. That generosity of order—intense yet breathable, decorative yet thoughtful—is why the image remains companionable over time.

Conclusion

“Odalisque by the Red Box” is a compact manifesto of Matisse’s Nice-period practice. A reclining figure, a striped wall, a patterned floor, and a few tuned objects are arranged so that color becomes architecture, pattern becomes rhythm, contour becomes breath, and calm becomes an achieved condition. The odalisque is not a fantasy of elsewhere but a modern instrument for harmony. With one small scarlet box, Matisse shows how a decisive accent can lock a room’s climate in place and make looking feel like listening to a chord held just long enough to reveal its inner life.